California’s world-class toy industry produced its share of iconic dolls, games and gadgets.

In 2001, Barbie faced her first real competition when MGA’s Bratz hit the market. Lena Lir Shutterstock

California Local has delved into several of the industries and enterprises that fuel the state’s economy, including agriculture, fossil fuel production, aerospace manufacturers, and software companies.

Here we look at product designers who took on more frivolous pursuits, using the materials made available by the proliferation of plastics manufacturing and the postwar baby boom to make California a powerhouse for toy production.

The most famous of these toys is Barbie, who always seemed like a California girl even before she morphed into Malibu Barbie. But there are other iconic playthings that were created or brought to market in the Golden State.

Way before companies such as Mattel and Wham-O began selling mass-produced plastic novelties, one of the most beloved childhood toys was born in Southern California. After Walt Disney and Ub Iwerks co-directed Steamboat Willie in 1928—the first cartoon to feature Mickey Mouse—seamstress Carolyn Clark decided to make a plush toy based on the soon-to-be-famous rodent. She enlisted the help of nephew Bob Clampett, a soon-to-be-famous cartoonist, who sketched Mickey while watching the cartoons in a movie theater.

Clark showed her wares to Disney, who was captivated. He helped Clark assemble a team to work out of “the Doll House,” a facility near Disney Studio on Hyperion Boulevard in Hollywood. When demand exceeded supply, Disney tried to scale up with a larger manufacturer, but he was dissatisfied with the results and instead opted for a McCall’s pattern so parents could sew their own Mickey at home. Reproductions of Mickey, Minnie and other Disney characters long ago moved into mass production, with complicated licensing deals, but the original Carolyn Clark creations are highly valued by collectors of Disneyana.

Its name may have come from a Connecticut pie company, but the Frisbee itself has solid roots in California. Utah-born Walter Frederick Morrison, who moved to the Golden State at age 11, started tossing around a popcorn tin at a family Thanksgiving dinner back in 1937. But it wasn’t until a decade later—after he’d moved on to playing with cake and pie tins—that Morrison saw dollar signs when fellow beach-goers in Santa Monica asked where they could buy the disc.

Morrison partnered with a butane salesman from Paso Robles named Warren Franscioni to craft a plastic version; they called it the Flyin’ Saucer, aiming to cash in on the UFO craze. The idea didn’t take off, but Morrison persevered and sold his “Pluto Platter” to Wham-O, which released it in 1957. Thanks to some design tweaks by Wham-O employee Edward “Steady Ed” Headrick, sales skyrocketed.

The long-lived Morrison (1920-2010) penned the history of his invention in Flat Flip Flies Straight: The Origins of the Frisbee, while Franscioni’s efforts to profit from the invention were less successful. But Headrick did more than just tweak the design; he also founded the International Frisbee Association and later co-founded the Professional Disc Golf Association. And when he passed away in 2002 at his home in La Selva Beach, California, Headrick specified that his ashes be mixed into plastic and incorporated into a limited-edition Frisbee run.

Necessity may be the mother of invention, but why invent when it’s easier to adapt? Wham-O, one of California’s most prominent toy brands, excelled at the latter.

Company founders Richard Knerr and Arthur “Spud” Melin—two University of Southern California graduates who formed Wham-O in the Knerr family garage in South Pasadena—had an eye for the “next big thing.” Their first product adapted the slingshot design—an object as old as, well, the Bible.

Around the same time they picked up the Frisbee, Knerr and Melin began making the Hula Hoop—a trademarked version of traditional hoops used for play in many cultures. Within the space of four months in 1958, 25 million Wham-O Hula Hoops® were sold.

In the late 1950s, conventional toy industry wisdom held that little girls wanted to play only with baby dolls that had names like Betsy Wetsy, because their ultimate goal in life was to be mommies. But Ruth Handler, CEO of Los Angeles toymaker Mattel, had an idea that would birth a cultural icon (both adored and despised) and become one of the best-selling toys ever made.

Handler’s epiphany was to create a doll that allowed little girls to envision their futures as grown women—adults with careers, stylish clothes and, perhaps most revolutionary of all for that era, fully developed figures. In 1959, the toy that Handler envisioned hit the market. Barbie was an immediate hit, with 350,000 sold in its first year.

Today’s Barbie is a very different doll. After decades of controversies over her unrealistic measurements and idealized whiteness, Mattel embraced Barbie diversity. The first “Black Barbie” and “Hispanic Barbie” had been released in 1980, but starting around 2015 Mattel began marketing Barbies in a variety of body types and ethnicities, including a “Wheelchair Barbie” with a prosthetic leg. The new, diverse Barbie line paid off. In 2021, Mattel sold a record $1.7 billion worth of Barbie dolls worldwide.

The ultimate game to play on a suburban lawn was created in the ultimate suburb. The idea came from Robert Carrier, who worked as an upholsterer for a boat manufacturer and was living in Lakewood, a postwar planned community that was credited with “altering forever the map of Southern California.”

Carrier returned home one day in 1960 to find his son playing with his friends by scooting along a wet stretch of painted concrete. The next day, he brought home a roll of Naugahyde and put it down on the driveway as a safer option for play. He went on to get a patent for a refined version with a tube sewed into the side that formed an “irrigating duct.” The shrewd minds at Wham-O quickly made a deal with Carrier and debuted the Wham-O Slip ‘N Slide Magic Waterslide at the Toy Fair trade show in February 1961. By September of that year, more than 300,000 slides were gracing back yards across America.

Slip ’N Slide can still be purchased today, despite the fact that it’s not entirely safe for adult use. Given the simplicity of the product, it’s not surprising that there are many knockoffs, yet Wham-O has continued to protect its trademark yellow hue. As the company wrote when the toy turned 50, “if it’s not yellow—it’s not a Slip ’N Slide.”

A decade after his wife, Mattel CEO Ruth Handler, came up with the idea for Barbie, company co-founder Elliot Handler concocted another idea, this time for a toy aimed specifically at boys: Hot Wheels, a line of miniature, highly realistic die-cast model cars that actually rolled.

Not under their own power—the cars ran on the force of gravity, on distinctive, bright-orange plastic tracks (though from 1970 to 1978, Hot Wheels also produced “Sizzlers,” a line of motorized, battery-powered toy cars). But the initial Hot Wheels cars could hit speeds the scaled equivalent of 200 miles per hour. The first set of 16 Hot Wheels cars, kicked off by the now-iconic blue “Custom Camaro,” were created by a former General Motors automotive designer named Harry Bentley Bradley.

Bradley was pessimistic about Hot Wheels’ sales outlook and returned to GM after a year. He was wrong.

Hot Wheels were not an original idea—British company Lesney Products had been making Matchbox cars since 1952—but the new wheels quickly and completely dominated the toy car market. By 2022, Mattel was selling more than $1.2 billion worth of Hot Wheels toys globally every year. In 2018, when Mattel marked Hot Wheels’ 50th anniversary, the El Segundo-based company had produced about 6 billion of its toy cars.

Today’s teens play computer games in visually complex environments filled with frenetic action—but it all began 50 years ago with a white dot moving across a monochrome screen. Nolan Bushnell, co-founder of Sunnyvale-based Atari, gave new hire Allan Alcorn a training exercise; the engineer’s facsimile of table tennis grew into Pong, the first commercially successful video game. (This was way before Bushnell launched the Chuck E. Cheese pizza-plus-video-games chain, so Pong was tested in a Sunnyvale bar, Andy Capp’s Tavern, that is now the comedy club Rooster T Feathers.)

Bushnell originally planned to license the game to Bally or Midway, but he decided Atari would make more money by manufacturing it instead. In 1972, Atari rolled out a console for use in arcades and bars; next came Home Pong, released through Sears in 1975.

How significant was Pong? Despite its similarities to an earlier tennis game for the Magnavox Odyssey console, Pong won in the marketplace. Steven Kent, author of The Ultimate History of Video Games, sees Pong and Atari as key players in the video arcade boom and considers the release of Home Pong to be the beginning of home video game consoles.

Like the creator of the Slip ’N Slide, engineer Scott Stillinger’s contribution to toymaking history was inspired by watching his two young children attempt to play catch at their home in Campbell, a suburban town in Silicon Valley. Stillinger set out to build a better ball—one that couldn’t bounce out of reach, shouldn’t be easy to drop, and wouldn’t hurt if it accidentally hit someone. Using a box of rubber bands and the skills he learned studying product design at Stanford University, he cobbled together a prototype.

In 1986, Stillinger showed the squishy handful of rubber to brother-in-law Mark Button, who had worked in marketing at Mattel; they quit their jobs and started OddzOn Products. By 1989, Koosh was in 14,000 toy stores across the U.S. and available in 20 countries. There were eventually three Koosh varieties—regular, fuzzy (with twice as many rubber filaments), and Mondo (grapefruit sized)—and before it was acquired by Hasbro in 1997, OddzOn had diversified to some 50 products.

Like many inventions, Koosh had its share of copycats as well as a problem with getting a copyright—a matter ruled on in 1991 by future Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg, then a circuit judge for the U.S. Court of Appeals in Washington, D.C.

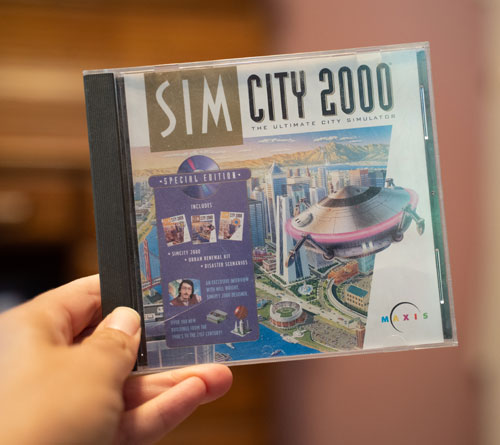

Where destruction reigns supreme in many of the most popular video games, construction is at the core of SimCity. Players design their own town, dividing the land into commercial, industrial, or residential zones; they build a power grid and transportation systems and then begin construction for the residents, who are called Sims. The choice of what type of construction—new houses, apartment complexes, commercial areas, hospitals, industrial buildings, churches—is based on such factors as the availability of electrical power, the type of surrounding development, and neighborhood crime levels.

The game was developed by Will Wright for his Orinda-based company, Maxis. Due to its unique character, video game publishers feared it would fail commercially. It wasn’t until 1989 that Broderbund eventually agreed to distribute it.

Wright and Maxis developed other titles, including SimEarth. After his home was destroyed in the Oakland-Berkeley Firestorm of 1991, Wright developed The Sims, a game where players engage in daily activities in a suburban household, including building a home from scratch.

In 2007, at the annual Game Developers Conference, SimCity made it onto the inaugural “game canon,” a list designed to be an equivalent to the National Film Registry. Matteo Bittanti, a researcher at Stanford University, told The New York Times the game is “one of the most important art works of the 20th century.”

Thanks to MGA Entertainment Inc. (short for Micro-Games America), the San Fernando Valley is home to its own toy giant. Founded in 1979, it occupies a campus in the Chatsworth area, and is known for such brands as Little Tikes and its animation arm, MGA Studios. No product line has approached the success of Bratz. The doll line began in 2001 with the introduction of four 10-inch hotties sold as a set: Yasmin, Cloe, Jade, and Sasha. They were ethnically diverse, but all shared makeup-encrusted doe eyes, pouty painted lips, and hairdos that would appear to owe a debt of gratitude to extensions.

The first dolls to successfully rival Barbie, the Bratz were created by Carter Bryant, who was working for Mattel in 2000 (though he claimed he had gotten the idea while on a seven-month break two years earlier). Two weeks before he quit Mattel, he sold his doll concept to MGA. (Lawsuits ensued—as chronicled by Jill Lepore for the New Yorker.)

These 21st century foxes may not present as career women in the way that Barbie did, but they seem to know their way around the media landscape. Like successful influencers, some of whom seem inspired by their look, the Bratz worked multimedia hard, appearing in films (albeit straight-to-video), television and web series, interactive DVDs and video games. Off the market for a while due to legal wrangling, the Bratz came back in plenty of time to mark their 20th anniversary and are still going strong on social media in 2023.

California Local writer Jonathan Vankin co-wrote this article, contributing the items about Barbie and Hot Wheels.

Article exploring songs, books, movies and other works from art and culture which feature our beautiful state.