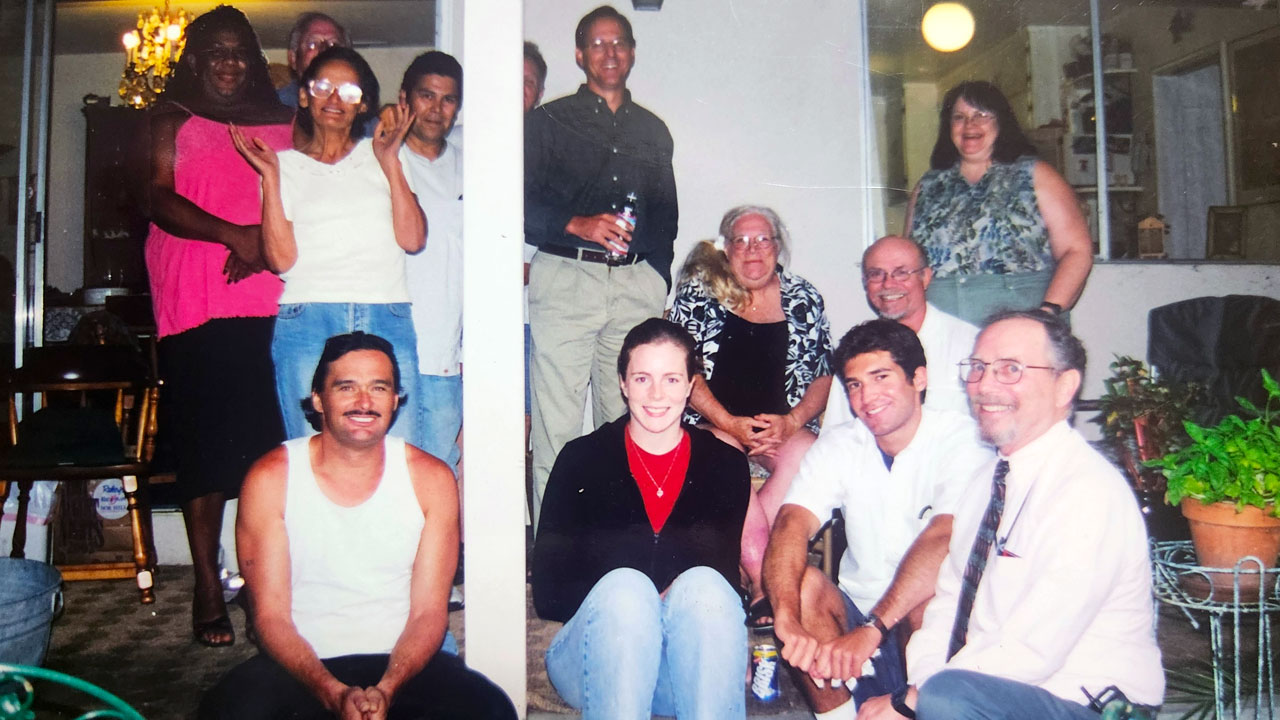

Founding CEO John Foley and others speak about SSHH’s roots and early successes

Terrie Tabb, who joined the SSHH program with a friend in 2010, says, “They took us in and gave us our first place to stay.” Graham Womack

Sacramento, with a population of just over half a million, has more homeless residents than San Francisco, whose population tops 850,000. Despite decades of effort to fix the problem, it has only gotten worse in recent years. This is the second part of an investigative series about the demise of Sacramento Self-Help Housing, once renowned for helping the neediest people experiencing homelessness. The first part of this series, published on February 19, looked at the fallout from SSHH’s collapse in the first half of 2023.

John Foley was finally poking his head out. Foley, 76, served as Sacramento Self-Help Housing’s founding CEO until January 2023, when the board placed him on administrative leave, effectively ending his job. Thereafter, two interim CEOs quickly cycled through before SSHH laid off 168 employees, closed its offices at 1010 Hurley Way, and filed for bankruptcy in late May.

Foley, who moved to Palm Desert in 2021 and commuted to Sacramento thereafter for his work at SSHH, laid low after being placed on leave. He says he’d been told by his board not to say anything. He resurfaced on June 13 after learning through longtime SSHH board chair Ted Cobb that it was okay for him now to speak publicly. Foley would give several interviews for this series.

Many years before its failure, SSHH’s roots and success in helping countless people experiencing homelessness would help set the organization’s course.

“I think almost everybody who was part of Self-Help Housing felt a sense of mission, a sense of call to do that work,” Foley said.

How SSHH Got Its Start

In 2021, Sacramento Self-Help Housing hit $15 million in revenue. Once, though, it was just a small group of people who thought they could fix up houses.

The organization was launched in name, though with a different mission, in April 1990. It stated in its articles of incorporation that it would “acquire, develop, rehabilitate, and manage housing for very low-income people,” according to documents on file with the California Secretary of State.

Among the people involved in the first iteration of the nonprofit was Ron Javor.

Javor, 78, grew up in Southern California. While attending University of California, Los Angeles, Javor said, he traveled to Delano on weekends during his senior year in 1966 to assist Cesar Chavez and striking farmworkers. He later spent a year building low-income housing in Visalia through Self Help Enterprises.

“I really wanted to be an advocate,” Javor said.

In the 1970s, Javor went to work as an attorney for the California Department of Housing and Community Development. He later served as staff counsel and deputy director. While working for the state, Javor led efforts in the early 1980s to secure the largest general fund appropriation for housing in the country at the time, for what he said was essentially a state rental housing program. Javor recalls he successfully pitched the idea to then-Gov. Jerry Brown during a plane ride from Los Angeles to Sacramento.

“His chief of staff saw me sitting in the back—I was a smoker,” Javor said. “I lit up, but then the flight attendant got on the mic and said, ‘Mr. Javor, please come up to the front of the plane.’ And I had 45 minutes to sell the program.”

Javor has achieved renown for his work in both housing and homelessness. In his home, he keeps an award that the California State Assembly gave him in 2015 for his work around homelessness. He can still speak extemporaneously about controversial policies like Article 34 of the California Constitution, which has made constructing affordable housing very difficult.

Sacramento County Supervisor Patrick Kennedy served with Javor on SSHH’s board in the mid-late 2000s, before Kennedy was elected to office. “When it comes to housing policy, and particularly the unhoused, he’s like the Yoda of housing in California,” Kennedy said.

In 1990, Javor, along with another veteran of Self Help Enterprises, Stan Keasling, decided to take what they’d learned and try to rehab houses in Sacramento. “We did one house,” Javor said. “And it turned out, rehab is very difficult, takes a long time, and nothing ever happens right the first time. So that was the only house.”

SSHH became delinquent with the state in 1991. Javor said the nonprofit transferred its assets to Emergency Housing, an organization that is now known as Next Move. SSHH would sit as a dormant nonprofit for close to a decade.

Around 1990, Foley was wrapping up an 11-year career as a Methodist pastor, which included work for a Roseville congregation. Foley said another Methodist pastor he knew, Dave Moss, got him involved with the homeless services provider Loaves & Fishes, where Foley went to work for the next several years. There, Foley said, he discovered a problem.

“A number of the folks that I … got to know a little bit were disabled folks getting disability benefits, but they weren’t able to really utilize the money very effectively to get housing,” Foley said. “So I started spending time talking with them.”

Foley said Loaves & Fishes executive director LeRoy Chatfield—who retired in 2000 and was unavailable for comment—let him do this work. In time, Foley became concerned that these people were being ripped off by the payees they’d designated to manage their money. His fears weren’t unfounded. Payees in the Sacramento area around this time, Foley noted, included notorious landlady Dorothea Puente, who killed some of her boarders but continued to cash their checks.

Chatfield set up a payee program around 1991 that allowed Loaves & Fishes to manage money and pay rent for disabled people. Foley hired a landlord liaison.

“Pretty soon after I did that, I realized that the fun part wasn’t sitting in the office on QuickBooks,” Foley said. “It was out there, engaging with landlords.”

In 1993, Loaves & Fishes launched a shared housing program, Friendship Housing.

Javor doesn’t remember when exactly he met Foley, but is sure they must have crossed paths at Loaves & Fishes. “He was mission-driven,” Javor said. “And I liked the concept of doing shared housing, which was something he was talking about.”

The idea would eventually spread, according to Emily Halcon, director of the Department of Homeless Services and Housing for Sacramento County.

“The shared housing model is that unique brand that Sac Self-Help Housing really developed locally and grew,” Halcon said. “You see it in other communities. And we now see lots of other providers doing it.”

In 1998, Javor wrote an article for the Sacramento Bee in which he mentioned Friendship Housing (with Foley listed as a contact person) and pitched an old idea: rooming houses.

“Offering traditional month-to-month leases but renting at about $150 or less per month, rooming houses provide single adults—sometimes with children—shared rooms, cooking facilities and other residential amenities,” Javor wrote.

By the end of the 1990s, Foley said, Friendship Housing provided homes for around 120 people. But by this point, Foley said, Chatfield “thought it was just too big and too far away from the Loaves & Fishes campus, so he found a small grant for us and spun us off.”

Javor and Foley launched their new version of SSHH on Jan. 1, 2000, expediting its tax-exempt status by turning to the dormant nonprofit of the same name that had once sought to rehab houses.

What SSHH Was Early On

For many years, SSHH was small and, generally, fiscally sound. In 2001, the earliest year that tax returns are available, the organization had $143,105 in revenue and $136,095 in expenses. At that time, its work was based around policy advocacy rather than housing hundreds of people.

Foley spoke to the Sacramento Bee in June 2001 as the Biltmore Hotel, a former single-room occupancy hotel at the corner of 10th and J streets in Sacramento, was in danger of being demolished.

“We think the city has a really stinky policy when it comes to these old hotels and we thought this would be a good occasion to call attention to it,” Foley told The Bee. The Biltmore escaped the wrecking ball, but sat vacant for years before being extensively damaged by fire in 2015. It no longer stands.

Foley and Javor also had some involvement over the years in the Sacramento Housing Alliance, a local policy-based group that advocates for affordable housing.

For years after Javor and Foley resurrected SSHH, it remained a small operation. Foley recruited his cousin Ted Cobb, a former California Environmental Protection Agency attorney who had begun his legal career as an AmeriCorps VISTA volunteer, to join SSHH’s board in 2005.

“We had nine board members and five staff members, and staff meetings were held in John’s office,” said Cobb, who became board chairman in 2011 and would serve in that role through the beginning of 2023.

Foley’s pay was very modest in SSHH’s early years, such as when he received $40,500 in 2003. SSHH’s tax filings as a nonprofit show him receiving no pay in 2001 or 2002, though he noted that he would have received a comparable amount for those years.*

His pay remained in this general range for many years before beginning to increase markedly in the late 2010s and reaching just over $127,000 in 2021. Still, even this is below market for nonprofit heads in the Sacramento region.

“We came out of Loaves and Fishes, which of course came out of the Catholic Worker Movement,” Foley said. “And there really wasn’t a sense of it being a career-type situation where you’d be compensated adequately.”

The work that SSHH and Foley did won praise locally during its heyday. And even after the organization’s collapse, there were still people willing to speak highly of Foley.

“I’ve never known a more caring, wonderful human being,” Kennedy said. “Not necessarily with a great deal of business acumen. But John led with his heart. And we need that in this community.”

Expanding Services

After bringing in an average of $150,000 in its first several years, SSHH’s revenue began to flow higher in the mid-late 2000s. SSHH noted in its 2007 tax return that its annual revenue was more than $500,000 and that it had “housed 145 individuals in our shared housing called ‘Friendship Housing.’”

The organization was getting positive media attention around this time for its work.

“If it wasn’t for Self-Help Housing, I’d still be living in a shelter trying to save up to get a place,” a former chronically homeless man named Steve Garrett, who was living with others in a downtown Victorian overseen by SSHH, told the Sacramento Bee in 2008.

Monitors in SSHH shared housing were sometimes formerly homeless people. Even staff sometimes came from unlikely places.

Jeremy Baird, 50, served as SSHH’s final interim CEO over its last two months and is now regional program manager for City Net, which is county’s new vendor for its scattered-site shelter program. Baird said he was originally hired by SSHH in 2013.

“There were only about 12 to 15 permanent staff members for those first five or so years that I worked there,” Baird said. “We just were very tight-knit, very much like a family outfit. Just kind of informal. We had the attitude of, ‘Do whatever it takes to make it work.’ Nobody was really an expert in the field. At that time, we were just an upstart agency.”

In the mid-late 2010s, however, things started to change. In 2014, the county voted to abolish its Regional Human Rights/Fair Housing Commission. The Sacramento Bee noted that the commission had struggled “since an audit by area cities found questionable spending and work practices.”

Javor, who had served on the commission, said he spoke to a couple of commissioners and was able to get its leftover money and a tenant hotline moved into SSHH.

“My rationale was, if we can prevent homelessness, we’re doing as much good as we are by providing the housing,” Javor said. “And the board took a little selling, but eventually we did it. And that was the first big growth program, besides just getting housing money.”

There are signs that at some point, SSHH might have started overpromising and underdelivering to people it was helping. Terrie Tabb, who had previously experienced homelessness, joined the program with a friend in 2010.

“They took us in and gave us our first place to stay and I was very grateful for that,” Tabb said of SSHH. “And there was a whole lot of stuff that they didn’t do that they said they would.”

Tabb eventually went into independent living with assistance from SSHH, moving into a Gloria Drive triplex owned by Javor around 2016. She now has a private rental arrangement with Javor. He said he loses money but that he made a commitment to Tabb and her roommate.

The overall amount of money flowing to SSHH continued to rise steadily over the years, hitting $3 million in 2017. Around this time, SSHH also found offices at 1010 Hurley Way. where, in time, it would have space spanning two floors. The growth was coming as more and more people were beginning to experience homelessness in the greater Sacramento region.

It would set the stage for SSHH to morph from a small, efficient nonprofit into something entirely different.

Coming next week: Part 3—Growth and Problems for Sacramento Self-Help Housing.

* A previous version of this article stated that Foley took no salary for at least the first five years SSHH was in existence. This is inaccurate. His compensation was reported in a different part of SSHH’s tax returns early on than it was in later years.