This is part of an 8-article package of California Local stories about the energy sources that power California.

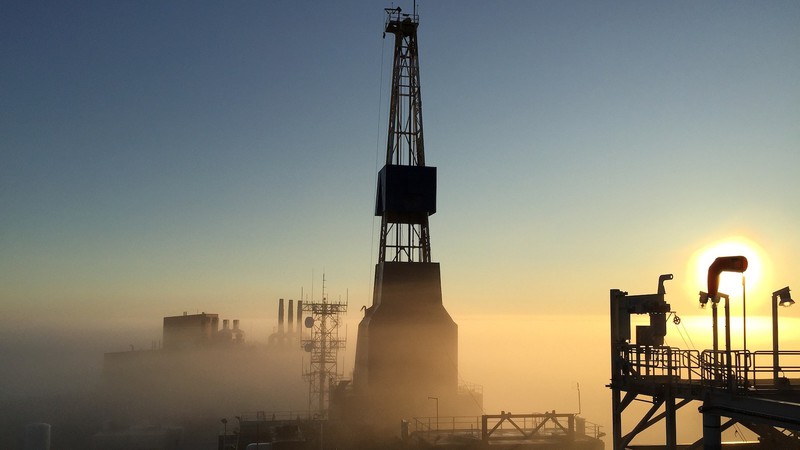

How did oil come to dominate both California's and the world's economy—and daily life? Shaun Undem / Pixabay Pixabay License

California is making progress toward its goal of becoming a net-zero carbon emissions state by 2045. With 24 years to go, the state drew slightly more than one-third of its electricity from renewable sources in 2021. The problem is, electricity is far from the whole greenhouse gas emissions picture. In fact, according to California Air Resources Board (CARB) data, electricity generation accounted for only 14 percent of those climate change-causing emissions in the two decades beginning in 2000.

The worst offender when it came to pouring carbon dioxide into the atmosphere was the transportation sector—41 percent of all greenhouse gas emissions in the state came from transportation over the two decades covered by the CARB data. Most of that pollution, unsurprisingly, came from cars. According to a study at UC-Davis, 70 percent of transportation-sector emissions come from light-duty vehicles, in other words, cars and small trucks.

With more than 14 million registered automobiles, California far outpaces the state with the second-most, Texas, which has about 8 million, per 2020 data. So one thing is clear: if California wants to get to net zero in the next two decades, it will have to do something about all those cars. And what is it about cars that makes them so damaging to the environment?

The answer is simple: they run on gasoline, a fuel made from petroleum, also known as oil—the substance that provided 33 percent of all of the world’s energy in 2019, according to the Statistical Review of World Energy by the British oil giant BP. (All fossil fuels combined—oil, natural gas, and coal, provide more than 80 percent of global energy)

California is also the country’s seventh-most prolific oil-producing state, pumping out more than 134 million barrels (each barrel is 42 gallons) in 2021 alone according to U.S. government stats. Californians consume about three times as much oil as the state produces.

What is petroleum, and what can California do to stop using so much of it?

CARB handed down a ruling in August of 2022 banning the sale of all new gasoline-powered vehicles by 2035. There is no scenario for getting to net zero carbon in California that does not involve electrifying the transportation sector as fully as possible, according to a report by the San Francisco-based consulting firm Energy and Environmental Economics, Inc.

That’s because oil is not used much in the production of electricity. In fact, in 2021, California listed oil as producing only 37 gigawatt hours of electricity, which was counted as zero percent of the state’s total energy mix. Nationally, only one-half of one percent of electricity was generated using petroleum, though other fossil fuels, namely natural gas and coal, accounted for 60 percent.

But electricity may be the only part of the world’s energy picture that does not rely on oil.

Humans and Oil: The Early Days

A combination of the Greek word for rock, “petra,” and the Latin word for oil, “oleum,” petroleum is literally “rock oil,” so termed because it is found among the layers of rock that make up the Earth’s crust.

Many millions of years ago, the world was populated primarily by plants and algae. A type of green algae that lived in the sea has been found to be a billion years old, and may be the ancestor of every plant on Earth. In any case, over the course of millions more years, the prehistoric plants and algae sank into sediment and were buried under new layers of dirt and rock, where the Earth’s heat and the weight of the rock slowly but surely converted the dead organisms into the hydrocarbon-based substance we know today as “rock oil.”

Petroleum, believed to be the second-most abundant liquid on the planet (behind water), is not a recent discovery. As long as 6,000 years ago, settlers in Mesopotamia found a sticky, black substance seeping from between rocks on the banks of the Euphrates River. For centuries, the ancients used this semi-solid petroleum, which today we would probably call asphalt, as building and caulking material for a wide variety of structures from ships and stone houses to bathtubs.

What we would recognize as early oil wells first appeared in China, in about 347 CE. The ancient Chinese had discovered oil about 900 years earlier and used it to boil sea water for desalination, as well as to fuel fires for cooking and heating. Eventually, they figured out how to use iron rods and bamboo pipes to penetrate deep into the Earth and bring oil to the surface.

Of course “deep” in those days was relative. The fourth-century Chinese wells went down about 800 feet. Even wells drilled at the inception of the modern oil industry in the 19th century went down 1,000 feet or more.

How Dependent on Oil Are We?

The site of the world’s first oil well in the modern era was not in Texas, the Middle East, or any now-famous petro-state—but in Titusville, Pennsylvania. It was drilled by Colonel Edwin Drake, who was not a “colonel” at all (he just thought the title made him sound more serious), but a struggling entrepreneur of the type common in the mid-19th century, always on the make for some scheme that would let him earn a living and even, if he was really lucky, get rich.

Drake’s idea was to find some kind of fuel to burn in lamps instead of the increasingly expensive whale oil. And lighting lamps was, in fact, the primary use of oil in the ensuing half-century after he essentially invented the oil drilling industry. But in 1908, another entrepreneur, Henry Ford, introduced the Model T, which was not the first fuel-driven car but was the first that was priced to be affordable by large numbers of Americans. The era of car culture had begun, and with it, the era of mass oil consumption.

Well over a century later, according to the U.S. Energy Information Agency, gasoline—refined from crude petroleum—comprises 44 percent of all the oil used in the United States, where drivers burn through about 370 million gallons per day, 365 days per year. But while cars may be the biggest consumers of petroleum, along with diesel-powered trucks, and every variety of aircraft, the substance permeates our entire culture.

There are more than 6,000 items currently in general use that are produced from petroleum, according to the nonprofit energy information group The Norwood Resource. They range from fertilizers to Scotch tape, cosmetics to candles, dentures to surfboards, and hundreds of products in between.

Eliminating petroleum from daily life, then, will involve a far greater effort than converting to electric cars—though that will indeed be a significant step in the right direction. Freeing society from the grip of climate change-causing petroleum will mean revamping individual behavior and consumer culture from top to bottom.

Our Oil Addiction is No Accident

Consumer demand for cars and other products certainly drove the sudden dominance of oil over American, and global, society. And to be fair, life before the advent of petroleum was no walk in the park. Oil use improved the quality of daily life considerably. The transportation sector alone made daily existence insufferable in many ways.

In London, England, at the turn of the 20th-century transportation was almost completely reliant on a fleet of 50,000 horses who collectively dropped well over one million pounds of excrement in the city’s streets every day. Stateside, in New York City, the problem was even worse. About 100,000 horses produced roughly 2.5 million pounds of dung, plus an average of 200,000 pints of urine, on a daily basis. Not only did this create an unbearable stench, but the waste drew massive clouds of flies which spread typhoid fever and other diseases—as did the carcasses of horses worked to death and often simply left to decay in the street.

So the rise of petroleum, at least at first, appeared to solve a lot of problems and to make life much more tolerable. But the grip of oil, as opposed to other forms of energy over every aspect of modern life was not inevitable either. The giant corporations and cartels that created the market for oil are the same ones who now make it difficult to transition away from fossil fuels to renewable, carbon-free energy sources.

In 1870, John D. Rockefeller founded the Standard Oil Company, and within a decade Rockefeller had a near monopoly on oil production in the country—owning 90 percent of all oil refineries and pipelines. Standard Oil also controlled the world’s largest fleet of oil tankers. A 1911 Supreme Court decision broke up that monopoly, but in doing so also created most of the oil companies that continue to dominate the industry more than a century later. Chevron, Exxon (formerly Esso), Mobil and others were all formed from the splinters of Rockefeller’s original mega-corporation.

Until about 1970, the major U.S oil companies—which also included Texaco and Gulf—along with British Petroleum (now BP) and Dutch giant Shell Oil formed a de facto cartel known as the Seven Sisters. After various mergers and sell-offs, the giant companies are now generally referred to simply as “Big Oil.” But they continue to wield collective power.

They have a partner, however, in government, which serves as a foundational pillar of Big Oil’s power. According to a report by the International Monetary Fund, governments around the world shower oil companies with free cash, $5.9 trillion—$11 million per minute—in 2020 alone, equivalent to 6.8 percent of the world’s gross domestic product. Those subsidies, the IMF predicts, will reach 7.5 percent of global GDP by 2025. (Subsidies cover coal and natural gas as well as petroleum.)

How Governments Prop Up Big Oil

Two-thirds of those subsidies are handed out by just five countries, the United States, China, Russia, India, and Japan. They ensure Big Oil’s continued vice grip on the world’s energy economy. Why? Because they allow the oil companies to keep their prices low.

Drivers confronted with startling prices reaching up to $7 per gallon at the pump may scratch their heads at IMF’s description of oil prices as "low." But according to the IMF, more than 90 percent of the subsidies are handed out for no other reason than to let oil companies undercharge for environmental costs. “Efficient” pricing, that is prices that reflect the true and full costs of producing oil and other fossil fuels, would reduce global carbon emissions by 36 percent by 2025, generate revenue equal to 3.8 percent of world GDP and, not incidentally, would prevent almost a million deaths caused by air pollution, the IMF reported.

The G20, the organization of global states to which the five most prolific subsidy-granting countries belong, has resolved to phase out “inefficient” subsidies. But that resolution came at the G20's 2009 meeting. According to the IMF, the subsidies have only kept growing since then.

What’s the result of this consolidation of power in the hands of Big Oil, propped up by trillions of taxpayer dollars? The oil companies have an almost unlimited ability to block alternative energy initiatives. In the western United States, for example, 77 percent of public land that could be used for renewable energy such as wind and solar—and which have little or no potential for oil production—remain prioritized by federal and state government for oil and natural gas development, according to a study by the Center for American Progress.

Oil companies have used their government-subsidized vast resources to keep favorable policies like land use priorities firmly in place, through a network of highly-funded lobbying groups. The groups also push for cuts in subsidies for renewable energy sources. In 2013, according to the Environmental Defense Fund, the clean energy industry in the United States received only 1/75th the amount of subsidies doled out to oil and other fossil fuel companies.

“We need a Separation of Oil and State to reduce the fossil fuel industry’s ability to buy off politicians,” wrote the advocacy group Oil Change International in 2021. “We need to make a subsidy shift away from fossil fuels and towards renewable clean alternatives. And we need to free our imaginations from a fossil-dominated future.”

In 2022, the California Public Utilities Commission announced that California would be the first state to end subsidies for natural gas line hookups, a small but first step toward reducing the dominance of the fossil fuel industry. And Gov. Gavin Newsom has set a goal of ending oil extraction completely by 2045.

Long form articles which explain how something works, or provide context or background information about a current issue or topic.