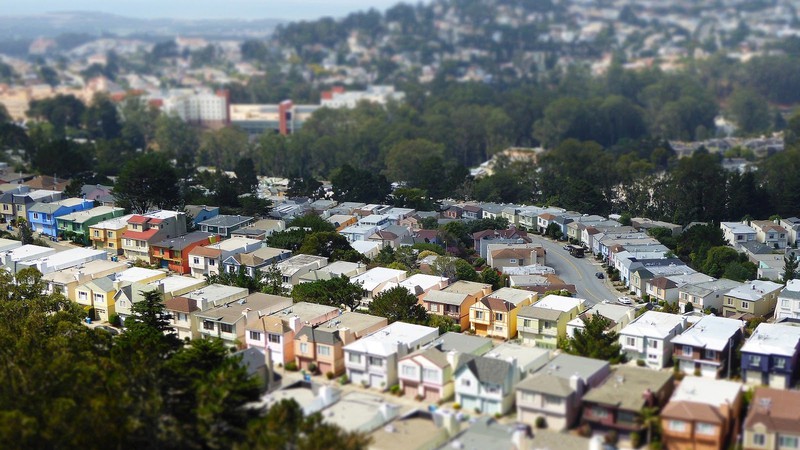

Over the past two decades, the Bay Area has seen almost 700,000 fewer homes built than would be required to provide adequate housing, according to a 2018 study. Photo by Mister Farmer / Pixabay Simplified Pixabay License

The coronavirus pandemic has ratcheted Silicon Valley’s housing crisis up to yet another new level of urgency. The Bay Area has some of the highest median rents in the United States. Now, residents are rapidly losing the income they need to pay those rents, threatening to turn the crisis into a full-fledged housing disaster.

But prior to the pandemic, the region’s housing shortage had persisted for at least 40 years, stretching the definition of “crisis.” A better description may be “chronic condition.” Without four decades of tax policy and zoning regulations skewed toward tightening the housing market rather than opening it up, the impact of the COVID-19 recession on the housing market would likely be easier to manage. Housing advocates, however, won at least a small victory last month when a Santa Clara County Superior Court judge ruled that a five-story, mixed-use development project in Los Altos could go ahead. The project had been designed to comply with California’s three-year-old SB 35 housing law, but was blocked by the city of Los Altos, according to a report by Dean Boerner of the real estate news site Bisnow.

The law—authored by San Francisco State Senator Scott Wiener—allows projects with at least 50 percent “affordable” units—that is, “affordable” by families who earn no more than 80 percent of the region’s median income—to get on a fast track to approval, according to Boerner’s report. But the Los Altos City Council put the kibosh on the 40 Main Street development anyway, claiming that SB 35 simply did not apply. Santa Clara Superior Court Judge Helen Williams disagreed, ruling that the city council “acted in bad faith” when it stymied the project. Wiener was also behind another housing bill that would have allowed for multi-family homes to be built on almost any property throughout the state, and allowed building heights to reach five stories when built in areas where large numbers of jobs are situated, as well as near transit stops. That bill crashed and burned in the state senate earlier this year, with critics saying that it did not do enough to create affordable housing, according to a report by Alissa Walker of the Vox Media-owned real estate news site Curbed. The bill freed developments of fewer than 10 units from affordability requirements. “And those developers could have simply opted to build their affordable housing requirements somewhere else, if they wanted to, for a fee,” Walker reported.

Wiener is now backing a new bill, SB 902, which would eliminate building rules throughout the state that limit developers to single-family homes. SB 902 would allow development of duplexes in small cities of fewer than 10,000 residents, as well as triplexes and fourplexes in larger municipalities, in areas where they would have previously been barred.

The bill would leave in place other local rules, such as height restrictions and design guidelines, according to a KQED report by Erin Baldassari.

“You can add a significant amount of new housing in a way that still fits into the neighborhood, in terms of the size of buildings,” Wiener told Baldassari, explaining “the beauty” of the new bill’s approach.

The bills are meant to address a problem that has been festering for decades—how to create enough homes for Bay Area residents. Between 2000 and 2018, according to a March 2020 “briefing paper” by the urban planning think tank SPUR, Bay Area development came up short by a staggering 690,000 homes, relative to the total required to provide adequate housing.

In that time period, the nine counties of the Bay Area built only 358,000 housing units combined. Only 42,500 were designated “affordable.” Most of the remaining units were rented or bought by what the study calls “those with higher incomes and/or higher levels of wealth.”

In that time period, almost two full decades, the Bay Area would have needed more than 1 million housing units to meet demand—including almost half-a-million aimed at residents with incomes below the regional median. Of the “missing” 690,000 homes, the Bay Area needed just 212,500 for those pulling in incomes above the median.

What happened to the people who couldn’t find housing in those 18 years, due to the construction shortfall?

“Some moved to other places, some decided to stay and pay more of their income toward rent and others never showed up in the first place,” wrote the authors of the SPUR study, “What It Will Really Take to Create an Affordable Bay Area.”

“Some live in overcrowded housing, doubling up with friends and family, or in units that are ill-suited to their family size.”

Still others didn’t go anywhere. They just kept living with their parents—or as the study phrased it, “delaying adulthood.”

According to SPUR, the Bay Area will now require 45,000 new homes every year until 2070 to meet a projected need of at least 2.2 million by that time. That’s about 25,000 more per year than the region managed to build in the 18-year period covered by the think-tank study.

The obstacles to building new housing go back to at least 1978 when the state’s voters passed Proposition 13, which placed severe limits on residential property taxes. That led local governments to place a premium on commercial development, which generated sales tax revenue, according to an analysis of California’s housing crisis published last year by Bloomberg.

And as Wiener pointed out in comments to The Guardian, the housing crisis can also be attributed to “restrictive zoning”—the very problem the San Francisco legislator’s series of housing bills are intended to address. California cities have made a practice of zoning primarily for single-family homes, driving up the price of housing and the land it sits on, as well as causing suburban “sprawl.”

Now, the coronavirus crisis has compounded the problem, with much new construction halted by state and county stay-at-home orders, and developers who are “less incentivized to build below-market-rate housing during an economic slowdown,” according to a San Jose Spotlight report by Nicholas Chan.

In March, however, San Jose passed Measure E, which places a new tax on properties valued at more than $2 million—a step “crucial” to pushing developers to build lower-cost housing, according to Chan’s report.

“Once we move past this health emergency, we will continue to have a housing crisis which will probably be even worse,” Wiener told the Spotlight. “So we can’t ignore housing. We have to continue to move forward with a pro-housing agenda.”