Professor Dustin Mulvaney chronicles the Santa Cruz County waterway’s destructive power

A view of the San Lorenzo River from the Soquel Avenue Bridge—which fared better in this storm than in 1982, when it collapsed. Chris Neklason California Local

During January’s storms, fueled by atmospheric rivers and king tides, environmental studies professor Dustin Mulvaney posted an eye-opening history of the San Lorenzo River and its destructive power. Below, with Mulvaney’s permission, California Local reprints his illustrated history.

The San Lorenzo River is a 29-mile-long river draining 138 square miles of the coastal slopes of the Santa Cruz Mountains to Monterey Bay. Its crystal-clear summer currents make it look like an idyllic silver ribbon running through the redwood forest. During the rainy season its powerful flows push away the sandbar that blocks its passage to the sea each dry season. Its winter flows attracted settlers who used its energy and water for lumber and paper mills, dams, and gunpowder production. Settlers learned to harness the power of the river. But every so often the San Lorenzo River becomes a raging torrent.

Spanish settlers met the power of the river soon after the Portola Expedition named it in 1769 and occupied what they called Alta California. They built their 12th mission in 1791 along the San Lorenzo river bank on fertile soil. After heavy damage from two floods in two years, they relocated the mission to an overlooking hill.

The new site they built above the river on Mission Hill is believed to be the location of Aulintak, a village of the Awaswas-speaking Uypi Tribe, who lived with the river for thousands of years. Today they are represented by the Amah Mutsun Tribal Band.

Flood of 1862

There are accounts of major San Lorenzo River floods in 1847 and 1852, but the first documented in local newspapers is from the Great Flood of 1862.

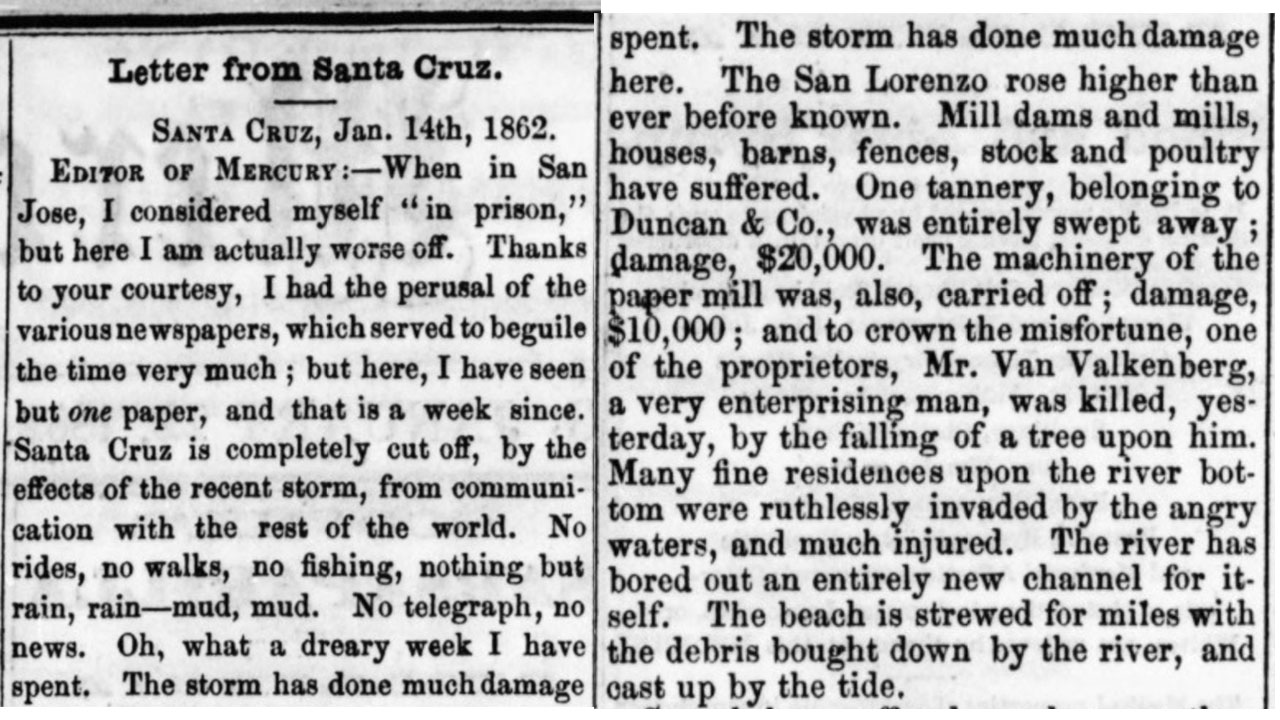

Letter from Santa Cruz, January 14, 1862:

“The San Lorenzo rose higher than ever before known.”

“One tannery, belonging to Duncan and Co. was entirely swept away.”

“Many fine residences upon the river bottom were ruthlessly invaded by the angry water, and much injured.”

“Soquel has suffered much more than Santa Cruz and Watsonville more than either.”

Flood of 1869

“The foot bridge across the San Lorenzo River is gone. Great fears are entertained for the safety of the new bridge on the same stream, near Santa Cruz”

Flood of 1871

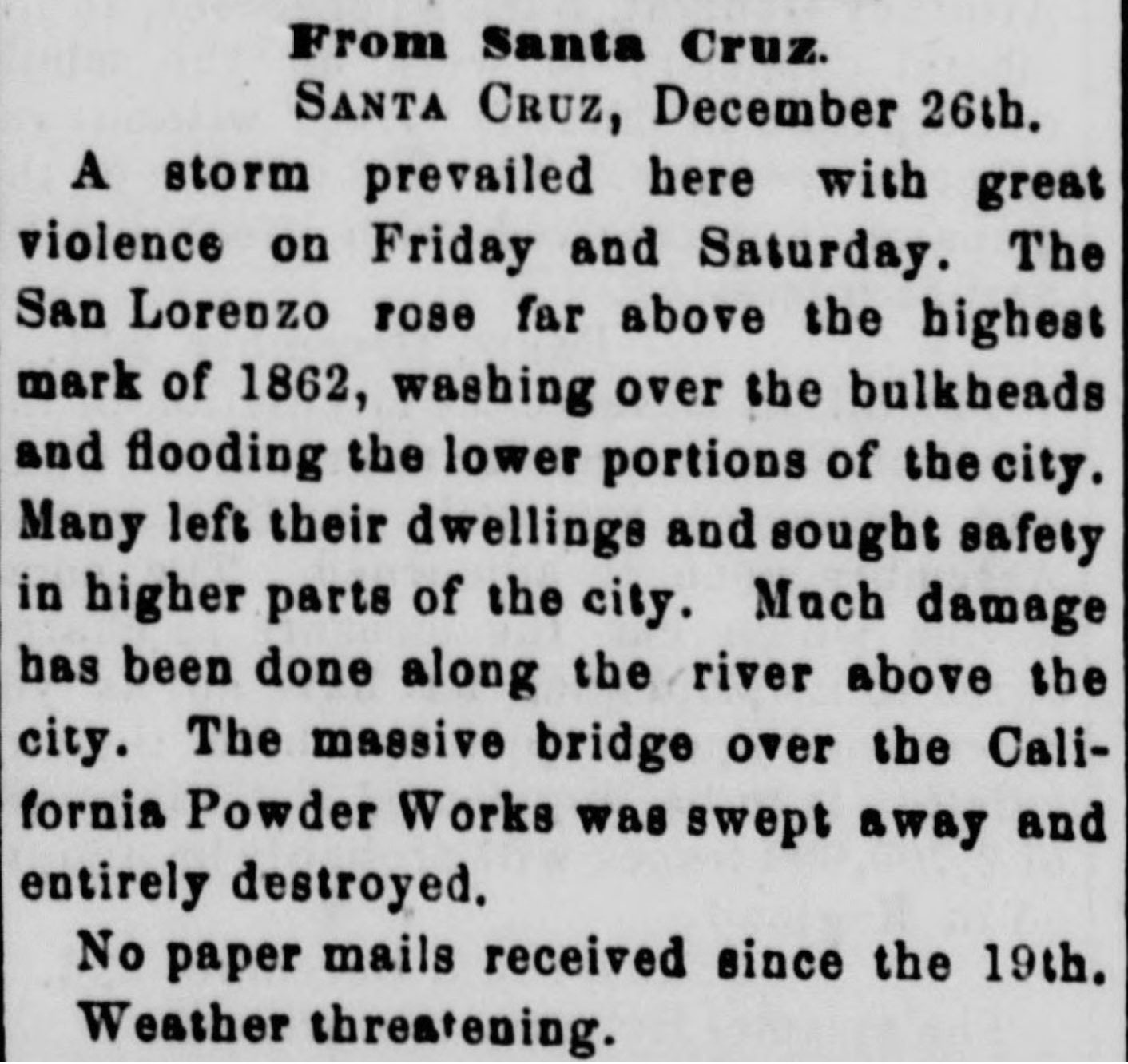

“A storm prevailed here with great violence on Friday and Saturday. The San Lorenzo rose far above the highest mark of 1862, washing over the bulkhead and flooding the lower portions of the city.” San Lorenzo Bridge in part destroyed, “about 240 feet of the bridge was carried away.” With one side of the city cut off from the other, a ferry helped people and supplies cross until it was repaired. An article from the Santa Cruz Weekly Sentinel says 23.5 inches of rain fell in 16 days in December 1871.

“A storm prevailed here with great violence on Friday and Saturday. The San Lorenzo rose far above the highest mark of 1862, washing over the bulkhead and flooding the lower portions of the city.” San Lorenzo Bridge in part destroyed, “about 240 feet of the bridge was carried away.” With one side of the city cut off from the other, a ferry helped people and supplies cross until it was repaired. An article from the Santa Cruz Weekly Sentinel says 23.5 inches of rain fell in 16 days in December 1871.

In the same 1871 storm, further upstream near what today is Paradise Park, “The massive bridge over the California Powder Works was swept away and entirely destroyed.” The powder works was built on land bought from paper mill destroyed in 1862; it was a vital industrial site especially during the Civil War resulted in blockades of explosives to the west. The powder works used the power of the river to make explosive powder from guano for California’s mining industry.

Flood of 1888

“A large amount of driftwood came down the San Lorenzo River this morning and struck the bridge of the South Pacific Coast Railroad, the force of which added to high water, sweeping the bridge out of line four feet, making it impassible.”

Flood of 1890

Again—“the river reached the highest point ever known.”

“20 feet of the upper bridge across the San Lorenzo River gave way, rendering the bridge impassible. ... 100 feet of the railroad bridge on the Southern Pacific, at the mouth of the river, fell into the water.”

Flood of 1906

“RIVER FRONTAGE WELL WATERED – The San Lorenzo quickly converted from peaceful stream into torrent.”

“RIVER FRONTAGE WELL WATERED – The San Lorenzo quickly converted from peaceful stream into torrent.”

“In addition to flooding the flat back of Bulkhead St., the water rose to Front St and the foot of Garfield St. was under water a good part of the night.”

January floods swept away Loma Prieta lumber Co.’s mill at Hinckley Creek stranding 11 workers overnight; Late March rain contributed to a mudslide at the mill site after April 1906 SF earthquake, killing 9.

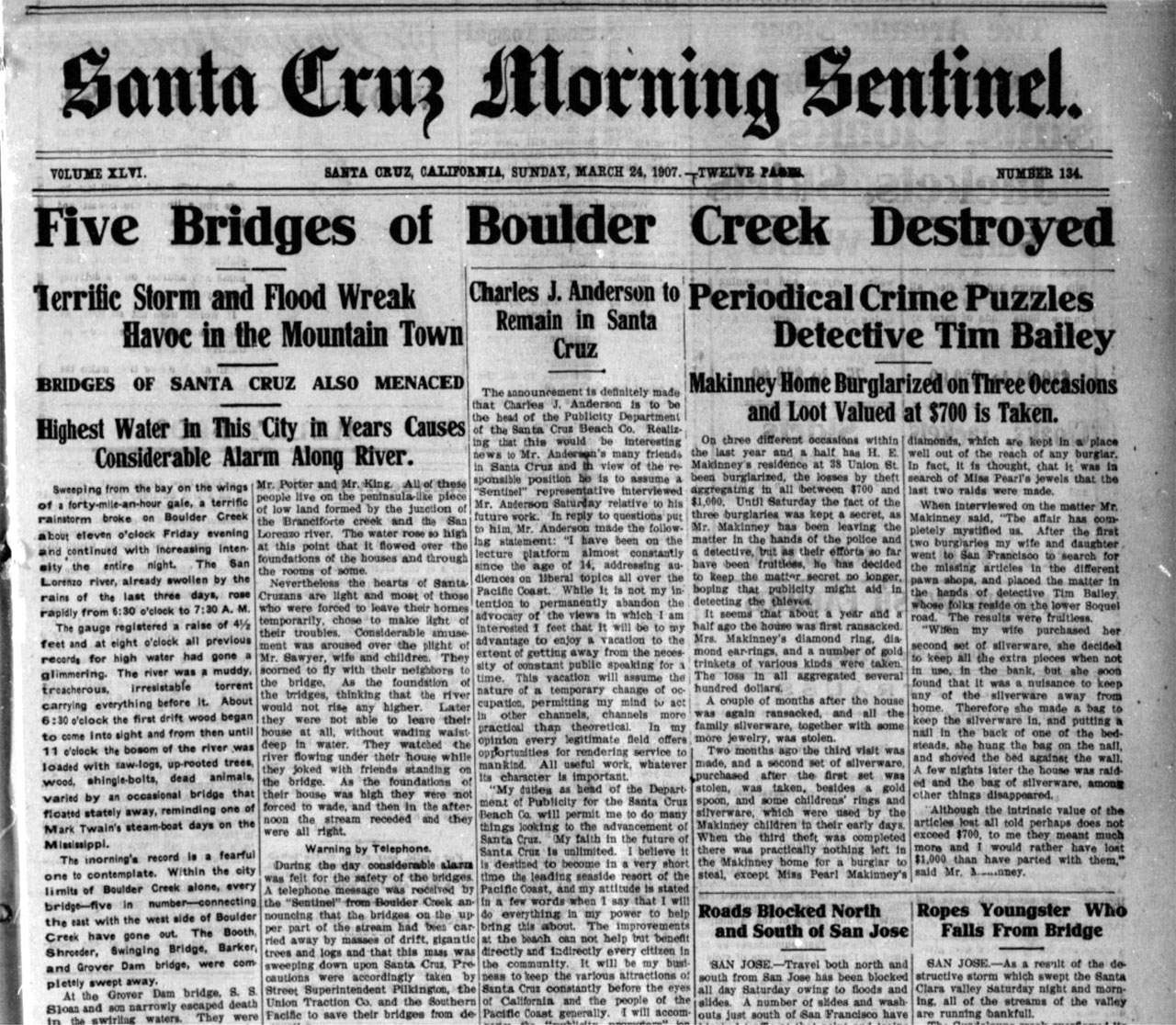

1907 Flood

Boulder Creek had some rough years 1904 to 1907. Curious how this wildfire, which burned for 14 months, and settler clear-cutting and grazing practices at the time contributed to the flooding and flood damage in 1907. #SantaCruzMountains

“The San Lorenzo Bridge on the Bear Creek Road is hanging in the air.” In Santa Cruz, “residents on Garfield St were evacuated.” Pacific Ave flooded at Sycamore, Spruce, Bulkhead. Note: Garfield Street was where San Lorenzo Park benchlands is today.

“The San Lorenzo Bridge on the Bear Creek Road is hanging in the air.” In Santa Cruz, “residents on Garfield St were evacuated.” Pacific Ave flooded at Sycamore, Spruce, Bulkhead. Note: Garfield Street was where San Lorenzo Park benchlands is today.

Businesses and residents had long sought flood control, and after storms there would be renewed interest.

In 1909, there was a push in the city for a bulkhead along the San Lorenzo river to be built by the railroads in exchange for track; this editorial “property holders, think!” emphasized how destruction to the watershed from deforestation was making flood risk worse.

But it wasn’t built, no funding.. so there were floods again in 1911, 1913, 1914, 1926.

Flood of December 28, 1931

San Lorenzo overflows banks for first time in 18 years. This 1931 storm was the first storm to shake the cement ship SS Palo Alto. It moved in three feet that year. (See Lookout Santa Cruz for footage of the ship’s fate in the 2023 storm.)

Floods of the 1940s

February 1940: “San Lorenzo on Worst Rampage of Century” (See image)

The February 1940 floods destroyed six of the nine bridges on Zayante Creek, a San Lorenzo tributary just upstream of Big Trees, and destroyed newly constructed cement bridges on Scott Creek and Liddell Creek.

March 1940: “San Lorenzo Threatens Again” (See image)

Garfield Street lowlands were evacuated several times in 1940 from raging San Lorenzo floods. City commissioned a report on flood control that year and the federal government funded flood control surveys.

February 1941: “Floods, Raging San Lorenzo Sweeps Through Santa Cruz” (See image)

Flooding in the 1950s

Proposals to reduce flood risk included removing a six-acre island from the river mouth, building dams up the San Lorenzo gorge and further upstream, and building a wall along the river.

The flood of 1952 saw log jams as the gage at Big Trees hit a record at the time of 24,000 cfs.

The deadly flood of 1955 flowed at an astonishing 30,400 cubic foot per second plus 8,100 cfs in Branciforte Creek. The confluence of those creeks was called the triangle of death. Downtown flooded in ten feet of water and nine died, including two inside their home on Garfield Street.

The 1955 storm was prior to the Army Corps’ excavating the channel and building levees, so there were a lot more homes and buildings in the floodplain ... and during flood stage, floating by in the floodwaters.

By 1958 the Army Corps committed to building levees—the island was removed and the river straightened. The Loch Lomond dam was built on Newell Creek, completed in 1960, and there was a proposal to dam Zayante.

Life After the Levees

The river height at Big Trees on the San Lorenzo was highest in 1982 than any other time on record (though the river at Ocean Street was higher in 1955), but the levees held through the city. The disaster from the 1982 storms would be the Love Creek Slide.

Levees transformed the river. Big flows in 1996, 2006, 2017, 2022, 2023 stayed in channel through the city. The river is less prone to damage or injury, but the river also no longer supports the coho and steelhead populations it once did. The San Lorenzo River prior to 1955 was famed for its fishing. Taming the power of the river has brought most the city safety from its raging torrents, but forever transformed the river in ways we are still trying to understand to bring back the salmon.

Dustin Mulaney, an environmental studies professor at San Jose State University, is the author of Solar Power: Innovation, Sustainability, and Environmental Justice. To see his original posts, with more historical images, read Mulvaney’s thread on Twitter.

Long form articles which explain how something works, or provide context or background information about a current issue or topic.