There’s more to celebrate than just the San Francisco underground scene.

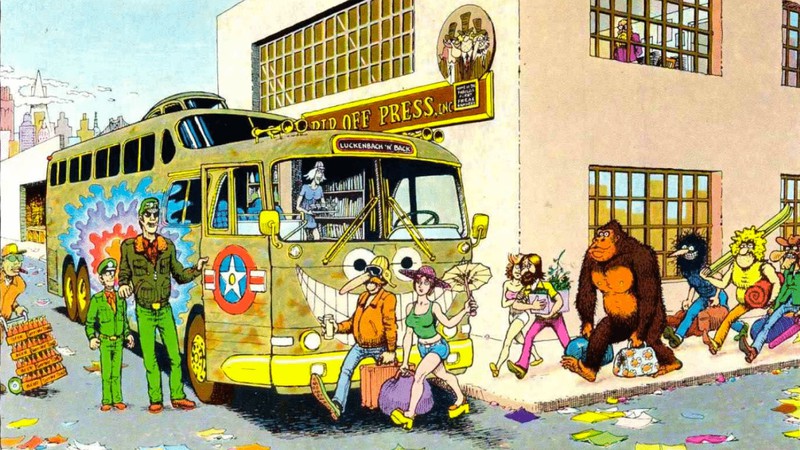

Rip Off Press, once located in San Francisco's Sunset District and now headquartered in Auburn, was part of a movement that blossomed in California. Drawing by Gilbert Shelton from Rip OffComix #9 Courtesy Fred Todd & Rip Off Press

People come to California for freedom, and one of those freedoms is the freedom to draw. Our state’s central place in the wave of adult, autobiographical and underground comics can’t be overstated—especially in the unrestrained exuberance of cartooning’s heyday, roughly 1967 to 1993.

These below-the-radar comics, made in California, are a perennially out-of-bounds form of art. Generally they have something to outrage everyone, from conservatives furious about blasphemy to feminists disgusted by caricature. To the person who loves them, comics can have a mojo like nothing else, an irreplaceable energy.

California’s history as a lodestar for alternative cartoonists has something to do with the bicoastal cultural rift. As usual, NYC acted and California had an opposite reaction.

In New York the scrappy and disreputable comic book industry of the postwar years published reams of pulp about detective, superheroes, romance, wacky animals and horror tales. Blogger Blaise Tassone claims that 1952 was the peak year of comic book publishing, with some 2,800 titles out. Modern-day comics publishers will never see those numbers again.

Many of the cartoonists mentioned below would have been children in the early 1950s, delving through these tons of comics. The variety of what they later created is partly due to all the different kinds of material they saw.

Concerns about sex and violence in the comics led to the Comics Code of America in 1954. Dr. Frederic Wertham’s frighteningly titled Seduction of the Innocent caused the furor: a Freudian analysis of our national weakness for superheroes. The doctor had a point; sometimes horror and crime comics were too extreme for children. But Dr. Wertham feared homosexual subtexts and subliminal images would lead to juvenile delinquency.

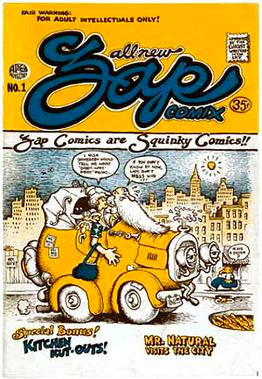

By 1954 the comics publishers agreed to accept the Comics Code to avoid censorship. Slick magazines didn’t have to subscribe to the code; Mad magazine could print their rule-breaking satire without interference.

The idea of publishing one’s own comics struck some Texans in the very early 1960s. Frank Stack and Gilbert Shelton were students in Austin; Stack’s still-funny The New Adventures of Jesus took on the epic Hollywood cruciflixes of the day.

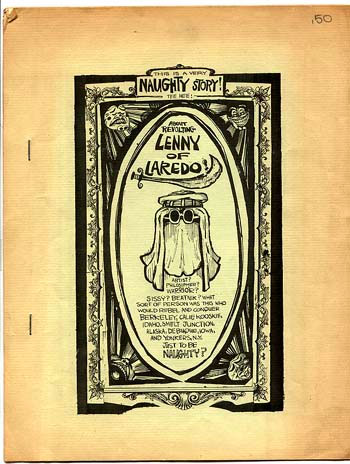

But the Pacific Coast’s first underground cartoonist, Joel Beck, was raised in El Sobrante. This unincorporated town has been called a bit of Bakersfield in the East Bay. In 1965, the Berkeley poster shop the Print Mint published Beck’s Lenny of Laredo, a burlesque of the career of comedian Lenny Bruce.

Beck’s pamphlet-sized comic came out years before the rise and fall of underground comics. Eventually the term “comix” debuted, spelled with an x to differentiate them from the caped and masked assets of Marvel and DC.

One could generalize that the first wave of comics, 1968–72, told of life on the street, of vivid sexual fantasies, wrenching personal experience, and satires of the pitilessness of the police. Sometimes they were mere laughing matters, obscene or ultra-violent versions of the cat and mouse comics of the 1950s. The targets of underground comics have aged—satires of forgotten mainstream comics, the Vietnam war, Spiro Agnew.

Many years later, Beck collaborated on his best work: Banzai! (1978). There he teamed up with two other artists, one being his childhood friend from El Sobrante, Roger Brand. (The third party on the book was the talented, funny and indefatigable Kim Deitch, a New Yorker and the son of the noted studio animator Gene Deitch.)

Amphetamines and alcohol ended Brand’s life early. But before he died, Brand gave Bill Griffith a couple of pages in a comic book he was editing for the Print Mint, Real Pulp Comics #1 (1971). It’s there that Griffith debuted his famous dadaist character Zippy the Pinhead.

Lines on Paper

The East Bay, then, was the launching pad for a national craze, those lawless comic books produced first by the hippies and then, years later, by the punks. But San Francisco, as always, got the credit. Mostly this is because of the success of Robert Crumb, who left his greeting card illustrating job in Cleveland to go west. In 1967, Crumb famously began selling his comics on Haight Street to passing idlers, using a baby buggy as a pushcart.

Crumb later complained that he’d been forced in Ohio to do cute drawings for hire (he worked at American Greetings under Tom Wilson, famous for creating the character called Ziggy). His libidinous and rage-fueled work is still very dangerous 60 years on. Pity the professor trying to teach something like Crumb’s 1969 Joe Blow to contemporary art students, as Chloe Maval describes it in an essay for The Gutter Review. How offensive is it? Enough so that Crumb was, for a time, ordered not to enter the city of New York by the mayor himself.

People imitated Crumb or thundered against him. Crumb would draw the unspeakable and then excuse himself: “it’s only lines on paper!” Still, there were obscenity busts galore.

When the summer of love ended and the messy days of speed and heroin overtook the City, the market crashed, leaving only four publishers behind. Crumb and his wife to be, Aline Kominsky-Crumb, moved to the sticks, outside of Davis in the pretty town of Winters. He had a friend that lived out there: the Pasadena-raised cartoonist Robert Armstrong, who played old-timey music with Crumb in their band the Cheap Suit Serenaders.

Crumb never stopped drawing, as is seen in Terry Zwigoff’s hit documentary about him. But the late 1970s represented a lull in comic publishing, a doldrums somewhat relieved by Arcade, an anthology put out by the Print Mint and edited by Art Spiegelman and Bill Griffith. These issues were some of the most intelligent comics being published. And unlike earlier comics, they didn’t neglect the female artists: the late Dianne Noomin and M. K. Brown were among those included.

Armstrong appeared in Arcade; he’s a serious painter, but he’s maybe best known for his badly behaved rodent Mickey Rat. Going after Disney is a natural response for a rebel growing up in Southern California, as Armstrong did. Another Arcade artist, North Hollywood’s Robert Williams, had a character called Coochy Cooty, a crab louse with a little feathered cap who’s visually not far from many animated Mickey knockoffs of the early 1930s. The Air Pirates—a group of San Francisco cartoonists—did what time would prove to be a fair-use satire of Mickey and Minnie. But back in the day, they felt the full fury of Disney’s lawyers; it’s a long and painful saga.

Low Art Goes High

While he was in San Francisco in the 1970s, Spiegelman published scratchboard-illustrated studies for what would become Maus, his Pulitzer-winning autobiographical comic. One installation was in the San Francisco-published anthology Funny Aminals (sic); the other was in Short Order Comics (1971). By the 1980s, Spiegelman had moved back to New York, where he and his wife, Françoise Mouly, created the graphic anthology Raw, intricately produced and at home in any fancy gallery’s shelves.

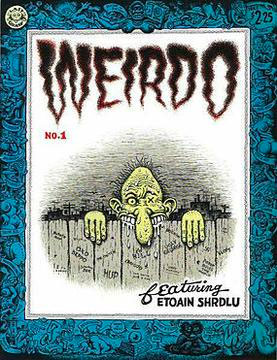

Once again, the West Coast reacted to NYC. Spiegelman went for high art, exposing America to the best comic talents in Europe. In reaction, Weirdo, published by San Francisco’s Last Gasp, went low, cryptic and strange—seeking outsider art, found objects and, as always, Robert Crumb. Weirdo was first published two months after Ronald Reagan’s inauguration in 1981. The magazine now seems a bold counter-reaction to all that enervating national optimism and obsession with fitness and wealth management.

Weirdo was, or could be, a rainbow of adult work, sometimes grim, sometimes juvenile. Still, it contained Crumb’s finest hours as a cartoonist, showcasing him as the one underground cartoonist who had excelled the most over the decades. Crumb’s slaved-over illustrations to Sacher-Masoch’s Psychopathia Sexualis or Boswell’s Journals raised Weirdo’s tone. These pieces rubbed shoulders with the kind of cartooning Weirdo’s later editor, Peter Bagge, aptly described as the work of bright high school kids.

Here was the last great flowering of California underground cartoonists. Kominsky-Crumb, who finished off the magazine’s run as editor, wanted out of the USA, to emigrate to France where cartoonists are revered. (Here’s an excellent summing up of Aline’s life and work, highlighting her pioneering of the autobiographical form.)

Focusing on the Crumbs neglects the dozens of early 1970s contemporaries beavering away in a range of styles and aptitudes.

Gary Arlington’s San Francisco Comic Company was an early direct comic book sales shop. The Hayward-raised collector’s cubby hole on 23rd Street hired cartoonists as employees. These were figures as unique as that shaky limner of scary monsters, Rory Hayes, as well as Dori Seda, an autobiographical adventuress whose work needs to be back in print, and will be soon.

The Mission was home to Manuel “Spain” Rodriguez, whose fantasies of bikers and big tough booted women were informed by his ardent left-wing politics. S. Clay Wilson dreamed up ridiculously violent yet well-spoken gangs of pirates of both sexes, including a blasé demon that looked like a horny toad in skin-tight checkered britches.

The still existent Last Gasp keeps up the tradition of rogue and outsider comics. Fearless publisher Ron Turner just came out with an anthology of the rowdy yet painstakingly drawn surrealism by Robert Williams, whose aesthetic is as appealing as the Route 66 bric-a-brac one finds in the desert, an array of chrome, skulls, carnies, hot rods apocalypses, ravening insects, and pinup girls. This well-read wit is an intricate artist. For years, he’s reveled in his personal idea of fun, and has managed to attract scads of uptown followers.

Comix Come Out

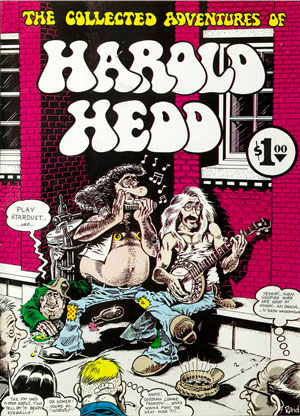

Unsurprisingly, gay comics in San Francisco also go back a long way. The British Columbian artist Rand Holmes, who drew the adventures of the ever-stoned hippie Harold Hedd, published a highly explicit gay storyline in 1971. It was all the more effective since Holmes was one of the best draughtspeople in the underground.

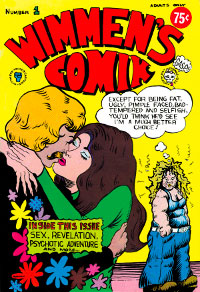

San Francisco’s Trina Robbins edited the earliest anthologies of women-created comics, a natural reaction to what was too often a boys-only scene. Robbins published “Sandy Comes Out” in Wimmen’s Comix, supposedly the true-life story of Robert Crumb’s sister. The rise of women cartoonists matches the rise of women’s liberation, and Robbins was there at the beginning; later on she was hired to pen Wonder Woman for a DC limited series.

Mary Wings, still alive and writing, is an out lesbian from the City, and she didn’t care for a straight woman’s angle on the subject. Thus she published her own Come Out Comics, seemingly the first comic book published entirely from a lesbian perspective.

Today’s San Francisco cartoonists follow the leads of these pioneers. On the one hand, it may be very, very hard to get paid for doing comics now. On the other hand, there’s no bar against publishing whatever you want…as long as you stay out of Florida. The Baylies is a web page gathering for SF Bay Area queer cartoonists and cartoonists of color. And the NYC-based webcomic The Nib, founded by Matt Bors, produces art from a political slant. San Francisco-based cartoonist and teacher Breena Nuñez is among The Nib’s roster of artists. They tell a story of their adventures of a trip back home and an encounter with a cursed block of El Salvadoran cheese.

Also notable from The Nib is an anthology on the subject of working for a living. You may recall the Faulkner quote that was the epigraph for Studs Terkel’s book Working: “You can’t eat eight hours a day nor drink for eight hours a day nor make love for eight hours—all you can do for eight hours is work. Which is the reason why man makes himself and everybody else so miserable and unhappy.”

Comix in the Capital

When the Crumbs spent time in Winters, there were other artists living and working in the Central Valley.

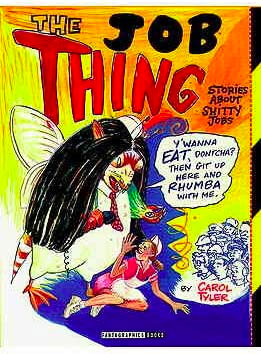

Temporarily, Sacramento was the home for Carol Tyler. When her book The Job Thing came out in 1993, it was clear she was going to be around for the long haul. Her subject was devastating workplace humiliations—not the cute foibles found in Cathy and Dilbert. She would later write and illustrate one of the most honored graphic novels about World War II, Soldier’s Heart. (It’s an unmissable book, deeply researched and suffused with compassion and pain, that required Tyler to do a bit of detective work to unearth the mystery of her father’s service in the winter of 1944-45.) Tyler is quite well known now, but in the 1980s life was sometimes a struggle.

There weren’t many other cartoonists in the scene, except in the outskirts. “Every now and then we’d go see the Crumbs or go to a party at Robert Armstrong’s place,” Tyler recalls.

“My time in Sacramento was mixed,” she told me. “I loved raising our daughter there, so those memories are sterling.” She and her late husband, graphic artist Justin Green—about whom more presently—lived on Elvas Avenue in a duplex.

“I really got my comics career started in that little duplex. I remember being so damn hot because we didn’t have an air conditioner, but it never dried out the ink in my pen because it was the old formula ink, shellac based.”

“A million trains went by on the levee. We had so much fun there. I worked at the Sacramento History Museum as the exhibit person for five years. Kept food on the table and we had health insurance. We traded artwork with Aline Crumb in order to get her used car, which allowed me to go to work.”

Tyler worked at an indie newspaper and tried to get her work syndicated but was told by editors “we already have a girl cartoonist”... meaning Lynda Barry. Faced with the bottoming out of the comic business at the end of the 1970s, Justin took up the trade of sign painter; an exacting business just right for his painstaking tendencies as an artist.

Tyler remembers, “Justin was the official state fair sign painter. That meant we got to go to the state fair whenever we wanted through that back gate.” When not doing hand-painted custom signs for businesses, Green created a regular comic for the sign painters’ trade magazines.

“Sign painting fizzled out during the time we lived there,” Tyler recounts. “So hard on Justin. He was a sign lettering master. He did not want to do vinyls. I’m here to publicly say I think the reason why the world is going to shit is because there are no more hand painted signs!”

She’s written about these troubled times elsewhere in her book Soldier’s Heart. Tyler is in mourning for her partner, who passed away in the spring of last year.

Justin Green, a sometimes San Franciscan, was originally from Chicagoland. Green was the composer of one of the undergrounds’ true classics and best-sellers, Binky Brown Meets the Holy Virgin Mary. This much-reprinted comic is the confession of an adolescent strung out on a lethal mix of clinical OCD and rock-ribbed 1950s Catholicism.

Green later worried about the book, calling it “a folly of my youth.” Yet it remains a masterpiece of the autobiographical comic and a solace to every former child dragged through the mysteries of a faith. Green was one of the geniuses of this era of comics. With these pioneers of the autobiographical comic, sex was not there to titillate as much as it was to illustrate the hook that’s deep in us all—in Kingsley Amis’ words, “to remind animals who are pretending not to be animals that they are animals.”

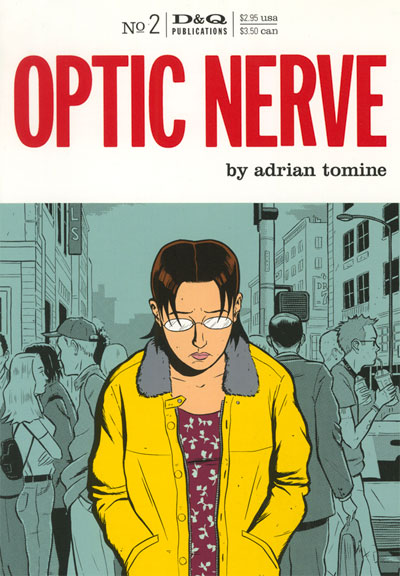

Adrian Tomine grew up in Sacramento; his Optic Nerve comics are similar to the work of Oakland’s Daniel Clowes, with similar moods of loneliness, disenchantment, and swallowed anxiety. I prefer Clowes for the depths of his disdain, and for enshrining the sweaty weirdos, glazed of eye and strange of demeanor…as well as the intelligence of his disenchanted young girls (as in his classic Ghost World).

But Tomine’s work has its own fine qualities. It is spare and delicate. Both artists draw perfectly accurate Northern California cityscapes that ought to look appealing, but are somehow too normal for comfort. Tomine’s work seems proto-cinematic: clear, cold and right to the point. The film of Tomine’s graphic novel Shortcomings—about a man simultaneously fighting and accepting his Asian heritage—debuted in 2023 at the Sundance Film Festival. It’s directed by Randall Park (who plays SHIELD Agent Woo in various Marvel franchises).

Sacramento’s nearby Sierra foothills were a refuge for publishers escaping the high prices of San Francisco.

Auburn is the HQ of Rip Off Press; their roof has been kept on over the decades by the Fabulous Furry Freak Brothers. This trio is currently in an animated series, having been given the Rip van Winkle plotline. Creator Gilbert Shelton, a Texan, lived temporarily in San Francisco before clearing out to Europe decades ago.

Grass Valley is home to the offices of San Jose-born Bud Plant, a giant in direct sales of comics. Plant’s business once included the Comics and Comix chain of stores, essential to Telegraph Avenue’s long lost bookstore stroll. San Jose’s place in the underground comic business requires an aside, thanks to one of the nation’s first direct-sales comics shops: Bob Sidebottom’s Comic Collector Shop. George Metzger (Moondog Comics, 1970) was also a San Jose local. His graphic novel Beyond Time and Again was reprinted in 2016 by Fantagraphics. Lee Hester’s much-missed Lee’s Comics brought a number of famed talents to the area on visits, from Melinda Gebbie to Jim Steranko to the 1990s’ Clowes/Bagge “Hateball Tour.”

Comic-Con and Beyond

For comics, as opposed to comix, California’s focal point is the San Diego Comic-Con, now the preferred occasion for movie studio revelations of sequels, prequels and spinoffs and this fiscal quarter’s MCU film. The gargantuan annual convention, held in July, is now 72 years old. It is the mobbed playground of giant communication companies, protected by a web of velvet ropes.

It’s a drastic change from the original purpose of the SDCC, which was a site for the study, worship and collection of lines on paper. Recently a counter-convention has come up, held in different vintage hotels in Old Town. Here fans gather…not to talk about release dates or script deals, but to inhale the scent of rotting old pulp in long cardboard boxes. (A similar roots comic book convention is taking place on a quarterly basis in Berkeley now.)

Connected to the convention, since it was a gathering of maybe 10,000 people tops, is cartoonist/historian Scott Shaw! (the exclamation point is self-styled). Shaw! drew for the Simpsons’ Bongo Comics and also animated Hanna-Barbera’s legacy characters such as Fred Flintstone. He’s a reliable student of the scene…and his lectures on the absolute oddness of old comics have no peer. Plus, his cartoon memoirs of growing up in San Diego are a treat.

Some could pinpoint San Diego’s emergence as a comic book town back to when Jack Kirby moved to San Diego. He was called “The King”: the most celebrated artist at Marvel, and the co-creator of Captain America, he spent his residual years in the San Diego sun.

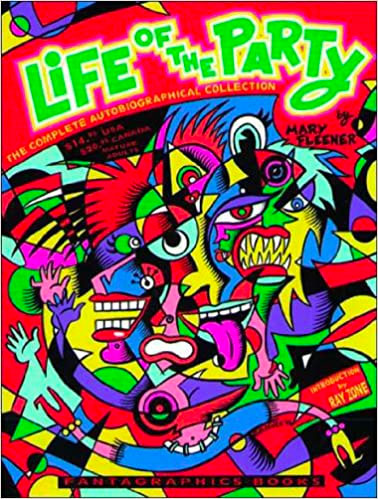

Farther up the coast in Encinitas is Mary Fleener, a hugely amusing autobiographical (and otherwise) cartoonist who loves to work in a jittery, manic cubist style. She’s currently writing a book-length autobiography about her wild life as a musician—her 1996 book Life of the Party is an outstandingly ribald and hilarious set of stories of LA-based degeneracy. Her newest work has been previewed in the South Carolina based periodical Mineshaft.

L.A. and Environs

In Los Angeles, a person who draws comics is likely going to be headed for a job in animation. While this is changing, 20 years ago a person who wanted to sit in a room and draw would rather have that room in Brooklyn or San Francisco. Despite that, the Los Angeles scene is full of feminists who distinguished themselves.

Barbara Mendes turned a storefront on Robertson in Beverlywood into a gallery with traffic-stopping murals. A while back, she was the co-editor (with Trina Robbins) of an all-female comic anthology titled It Ain’t Me Babe in 1970.

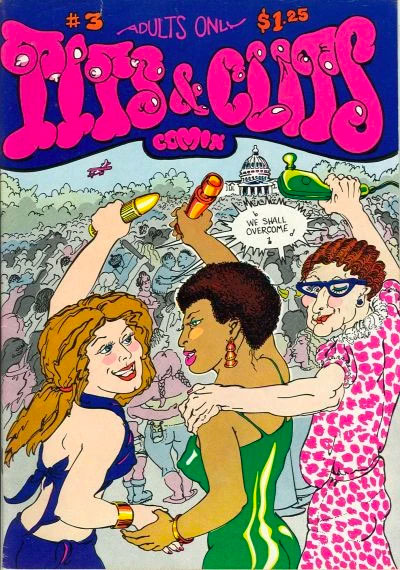

The complete 15-year-long reprinted run of Tits & Clits was released in March by Fantagraphics. Orange County feminists Joyce Farmer and Lyn Chevli wrote, drew and published their rejoinder to the id-rich comics of men. The two and their collaborators wrote about sex and menstruation with the kind of explicitness that brings out the cops: Laguna Beach’s Fahrenheit 451 bookstore, which at one point had been co-owned by Chevli, was busted for obscenity. Chevli and Farmer also wrote a comic book about five women’s stories of abortion, called Abortion Eve, which will be included in the anthology.

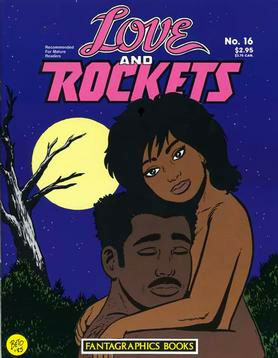

In their 40th year composing Love and Rockets comics, Los Bros Hernandez are perhaps the most eminent comic book artists in the Los Angeles area.

They were raised in a matriarchal family in Oxnard, a majority Hispanic, agricultural seaside town in Ventura County—“far from the city of class,” in Bruce Jay Friedman’s phrase.

Brothers Mario, Jaime and Gilbert put down an inimitable mix of fanboy action and tenderly observed daily life, on both sides of the US/Mexican border. Much was concerned with the duo of Maggie Chascarillo (Chascarillo–a jest, a funny story) and Esperanza “Hopey” Glass: an enduring friendship with benefits…and liabilities.

By the time Love and Rockets came out, the comic code meant less than it had in decades. Part of the rise of these artists had to do with Reaganism and the punk rock years, c. 1977-83—a small, short-lived but powerful societal leveling.

Second-wave undergrounders like the Hernandezes were stimulated by the direct-sales comic shops popping up all over North America. Suddenly, creators could hit the road; they had a circuit of stores to visit, meet fans, and make a little money. Love and Rockets is now well-known enough that it transcended the rep of out-of-the-code comix, and is now being honored by PBS and The New York Times.

In honor of the 40th anniversary, the Love and Rockets legacy is now republished in a whopping 50-issue reprint for those with a few hundred dollars to spare…worth every cent to see the endurance of their four decade-long saga.

Article exploring songs, books, movies and other works from art and culture which feature our beautiful state.