The California Journalism Preservation Act, which would force tech giants to pay for news, flew through the State Assembly, but opposition is massing.

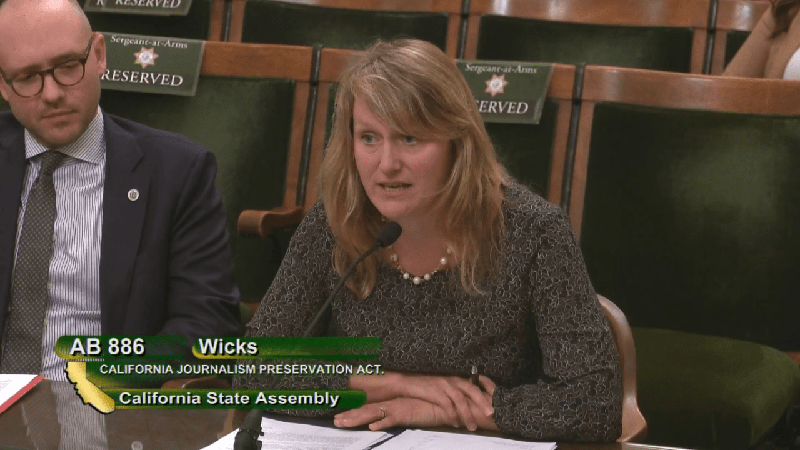

Assemblymember Buffy Wicks, author of AB 886, addressing the Assembly Committee on Privacy and Consumer Protection in April.

Katharine Trendacosta acknowledges an obvious point about the opposition to AB 886, a bill in the California legislature that could compel tech giants such as Facebook and Google to pay for news.

Some of the opposition comes from organizations with close ties to these companies, and is underwritten by the tech giants themselves. Then there’s the organization where Trendacosta serves as associate director of policy and activism, the venerable San Francisco-based Electronic Frontier Foundation (EFF).

“It’s strange bedfellows, right?” Trendacosta told California Local. “Civil liberties organizations and the tech groups aren’t often on the same side. But when it comes to these issues… it’s less about who’s on what side to us.”

Thus far, AB 886, or the California Journalism Preservation Act, has flown through the Assembly, most recently passing its third floor reading 55-6 on June 1. It will head in coming weeks to the State Senate to be heard by the Judiciary Committee. But to become law, the bill is going to have to clear some hurdles, including surviving a persistent effort against it led by people like Trendacosta.

The Road to the Judiciary Committee

AB 886 author Asm. Buffy Wicks (D-Oakland) has had her work cut out for her and others close to her bill, which could get its committee hearing on July 11.

“We’re still working on amendments and trying to really make sure that we’re addressing some of the concerns that I view as more valid,” Wicks said, "because my ultimate goal here really is to help our local newsrooms and that’s what I want to do with the bill."

Among these concerns has been that the bill could help enrich major media concerns or companies like Alden Global Capital that have swept up ownership of newsrooms in recent years. A similar fight cropped up when Australia passed a similar bill, which AB 886’s authors looked to as part of their inspiration.

“I think in Australia, the way that the debate took shape was sort of Mark Zuckerberg versus Rupert Murdoch,” Wicks said. “That is not a fight I care about. I don’t care about either of them.”

Wicks and others on the bill’s team have been talking with ethnic media and smaller publications to ensure they have a seat at the table. She said the team is also looking at amendments to ensure publications “have a significant California footprint.”

The California News Publishers Association has been a consistent supporter of AB 886, with its general counsel Brittney Barsotti helping craft the bill’s language and amendments. “It’s an incredibly important bill,” Barsotti said. “Legislators from our conversations seem to understand that there is a problem.”

Another group that’s weighed in on the bill’s language since early in AB 886’s legislative process has been the Washington, D.C.-based News Media Alliance.

“Our audiences have exponentially grown over the past 10 years and the opposite trajectory of our revenue has plummeted,” said Danielle Coffey, who became CEO of that organization on June 1 and was previously its general counsel. “If you looked at the arrows pointing, it’s almost the exact opposite.”

AB 886 has had little opposition thus far from other legislators, passing the Assembly Committee on Privacy and Consumer Protection on April 25 by a 9-0 vote and the Assembly Judiciary Committee on May 2 by 10-0. It’s also attracted a Republican co-author, Bill Essayli, who didn’t respond to a request for comment, along with Democratic co-author Josh Lowenthal.

Why the Opposition Hasn’t Gone Away

In addition to EFF, there are other civil liberties groups opposing AB 886, including the ACLU of Northern California. The digital news organization CalMatters has come out against the bill, too.

Chris Krewson is executive director of Local Independent Online News, or LION Publishers, which provides training and other programs to digital publishers, many of them small operations. Krewson, whose group opposed AB 886 while it was in the Assembly, said changes have made the bill “less bad,” but that he still fundamentally disagrees with its premise.

“This is just not written with those very small publishers in mind,” Krewson said.

While Krewson, a former journalist, doesn’t hide the fact that Google and Facebook underwrite LION’s programs, his company isn’t the only one to have benefited from tech. “It’s hard for me to argue that Google’s not paying its fair share to The New York Times, which I read,” Krewson said. “They have a significant nine-figure deal… That’s relatively recent.”

But perhaps the most unusual dissent from a tech-heavy group of opponents comes from Trendacosta: That bills like AB 886 would make it harder to break up arguable monopolies such as Facebook and Google.

“Because now, you’ve tied the fortunes of news to the fortunes of those companies,” Trendacosta said.