Can anyone make a Mickey Mouse cartoon now? Yes, but it’s not that simple.

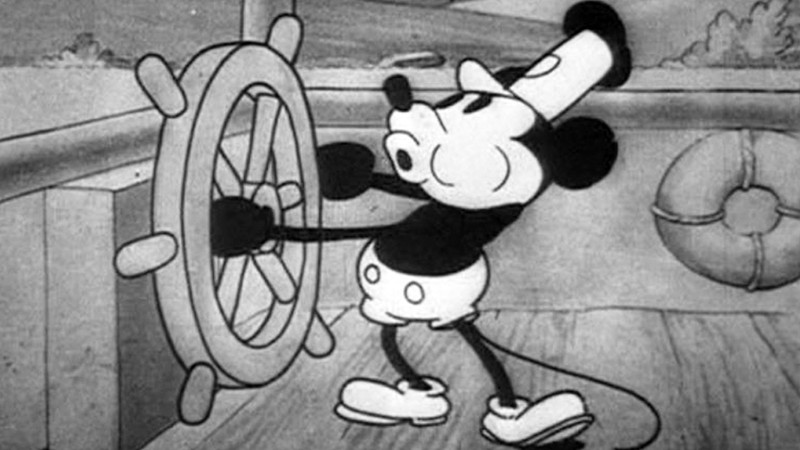

The version of Mickey Mouse seen in the 1928 animated short “Steamboat Willie” is now free for public use. Walt Disney & Ub Iwerks / Wikimedia Commons Public Domain

As soon as the calendar turned to 2024, the sixth-largest corporation in California lost control of one of its most valuable assets. Partially, at least. That corporation is the Burbank-based Walt Disney Company, the largest media conglomerate in the world, with a market value of $183 billion. The asset that it lost? Mickey Mouse.

As economics reporter Zachary Crockett of the site Priceonomics.com put it in a 2016 report, “every time Disney’s copyright on Mickey Mouse is about to expire, the law magically changes.”

To be specific, Disney did not lose total control of Mickey Mouse. But the earliest version of the iconic character entered the public domain on Jan. 1—95 years after its first copyrighted appearance, making Mickey Mouse free for public use. This means anyone can create a film or any other type of creative work featuring the version of Mickey Mouse from the 1928 short “Steamboat Willie” without having to pay a cent to Disney or worry about being sued for copyright infringement.

Disney, Mickey and Congress

Of course, the situation is not quite that simple. There remain restrictions and some potential legal peril to public uses of the Mouse. Still, the passage of Mickey Mouse into the public domain is a momentous event.

If it wasn’t, Disney would not have been spending millions to fight it at least since 1976 when, in response to relentless pressure by Disney and other entertainment corporations, Congress passed a new version of the Copyright Act, significantly extending the time period that copyright owners keep their creations under their own exclusive control. In 1998, Disney won another extension, up to the current 95 years.

As economics reporter Zachary Crockett of the site Priceonomics.com put it in a 2016 report, “every time Disney's copyright on Mickey Mouse is about to expire, the law magically changes.” According to data compiled by Crockett, just between 1997 and 2016, Disney poured almost $88 million into lobbying legislators in Washington, “mostly to influence copyright legislation.”

Mickey Mouse: “Fictional Billionaire”

Walt Disney, then an obscure, 26-year-old animator trying to make it in the nascent motion picture industry, with his creative partner Ub Iwerks, created the character in 1928. They produced three short films that year starring their cartoon mouse: “Steamboat Willie,” “Plane Crazy,” and “The Gallopin’ Gaucho.” Only “Steamboat Willie” was released in 1928. The films turned Mickey Mouse into an instant cash cow. Within five years, Mickey-related merchandise was pulling in $1 million per annum (about $24 million in 2024 cash).

Nine decades later, the Mickey money train was still accelerating. In 2018, merch featuring Mickey and other characters that came to comprise the Mickey Mouse universe did a cool $3 billion in sales. Back in 2004, Forbes listed Disney’s famous mouse atop its list of “fictional billionaires,” estimating Mickey’s total earnings at $5.8 billion that year.

Mickey and the California Economy

But the true value of Mickey Mouse to Disney—and by extension, to California—may be impossible to estimate. Mickey Mouse is possibly the world’s best-known corporate trademark, with a reported global name recognition of 97 percent, higher even than Santa Claus. The character and the company have been virtually synonymous for decades. The company itself, despite its wide range of culturally iconic characters and products, is colloquially known as the “House of Mouse.” When Disney and Iwerks created Mickey, their studio was located on a small lot in the Silver Lake neighborhood of Los Angeles that today is the site of a Gelson’s Supermarket.

In the U.S., the idea that ideas themselves should belong to the people who come up with them is almost as old as the country itself, though even the framers of the Constitution also believed that copyright should not last forever.

Today Disney is headquartered on a sprawling campus in Burbank, with offices and other locations in 18 cities across the United States and dozens more in countries around the world.

The Disneyland theme park in Anaheim—where one of the main attractions is the chance to meet and hug Mickey Mouse—makes Disney the largest employer in Orange County, with a planned expansion of the resort expected to add another 4,500 new jobs. A 2018 study found that Disneyland added $8.5 billion to the Southern California economy. And that’s not taking into account revenues generated by the Burbank film studio, whose movies raked in $4.83 billion at the box office in 2023.

So what will this change mean for Disney and California? To understand that, we need to understand exactly what copyright means and how we got here.

Copyright and the Constitution

In the U.S., the idea that ideas themselves should belong to the people who come up with them is almost as old as the country itself, though even the framers of the Constitution also believed that copyright should not last forever. In 1787, James Madison—the “Father of the Constitution” and later the fourth president of the United States—proposed that the foundational document include a provision that would “secure to literary authors their copyrights for a limited time.”

The provision made it into the Constitution. Article I, Section 8, Clause 8—which became known as the “Copyright Clause”—grants Congress the authority “to promote the progress of science and useful arts, by securing for limited times to authors and inventors the exclusive right to their respective writings and discoveries.”

Congress got on the job right away, passing the first copyright law in 1790, the same year the final state (Rhode Island) ratified the Constitution. The law, however, was extremely narrow. It protected only books, maps, and charts—and then for only 14 years, with the option to renew for another 14.

Over the next century Congress reworked and expanded the law numerous times, adding new requirements and instructions for obtaining a copyright, and most importantly adding new types of works eligible for protection. In 1856, dramatic works could be copyrighted, giving playwrights control of when and how their plays were performed as well as published. In 1897, musical compositions received the same copyright protections.

Photographs became copyrightable in 1865 and other works of visual art five years after that. “Derivative” works—that is, adaptations of existing works, translations, revisions or published works any other creative product “based on” existing ones—received protection in 1870 as well.

Copyright Terms Keep Getting Longer

Congress extended the lifetime of copyright four times since the original 1790 law. In 1831, the initial 14-year term was extended to 28 years, with a 14-year extension if properly requested.

In 1996, the Sonny Bono Copyright Term Extension Act—named for the 1960s pop music star who in 1994 was elected to Congress, and heavily backed by Disney—stretched the term to the author’s life plus 70 years for works created after 1977.

Then in 1909, the first major revision of the Copyright Act lengthened the extension period to 28 years, allowing authors to keep exclusive control of their works for a total of 56 years. The law also expanded the category of copyrightable works to include any type of authored creation, as long as it had an official copyright notice affixed to it somewhere. Works on which an author or publisher neglected to include the now-familiar © symbol, along with the date of copyright, immediately entered the public domain.

The 56-year term, assuming that authors filed for renewal (thousands failed to do so), remained in effect until 1976, when a new copyright law was passed. This one extended copyright to the full lifetime of the author plus 50 additional years. Copyrights held by corporations rather than individuals were extended to a flat 75 years.

For the first time, under the new law, copyright itself became automatic upon the creation of a work. There was no requirement that the work be published. And what was a “work,” anyway? In anticipation of new technologies that would give rise to new forms of media, the law blanketed all works created by “authors,” which meant any type of creator.

In 1992, another revision eliminated the need to renew copyrights on any work created after 1964. Renewals became automatic. Finally, in 1996, the Sonny Bono Copyright Term Extension Act—named for the 1960s pop music star who in 1994 was elected to Congress, and heavily backed by Disney—stretched the term to the author’s life plus 70 years for works created after 1977.

For works published from 1923 to 1977, the Sonny Bono Act now granted a new, 95-year copyright term. The law has not been revised since, and that’s why “Steamboat Willie” entered the public domain in 2024.

Disney itself, the company that spends millions to keep its own works out of the public domain, has built its empire on the public domain. Most of Disney’s most famous and influential films were all based on material in the public domain.

There is no “public domain” mentioned in U.S. copyright law, or the Constitution. That means there is no legal definition for what the public domain actually is. Basically, then, any work not copyrighted is in the public domain. That includes works such as “Steamboat Willie,” for which the copyright term has now expired, as well as works that are exempt from copyright laws—mainly government publications and documents (though not all of them)—and works that fall short on certain technicalities, mainly (for those created before 1989) failure to affix a copyright notice to the published work.

The Public Domain: an Embarrassment of Creative Riches

Promoting creativity and innovation is the purpose of having a public domain. Most of the greatest creative works in history are freely available in the public domain, from Shakespeare to Charles Dickens to Jane Austen to the Tao Te Ching. All are freely available not only to read and to publish, but most importantly to inspire and guide new works of creativity.

Disney itself, the company that spends millions to keep its own works out of the public domain, has built its empire on the public domain. Most of Disney’s most famous and influential films—Snow White, The Little Mermaid, Alice in Wonderland and others—were all based on material in the public domain. Even the first appearance of the modern Mickey Mouse (the one that won’t be in the public domain until 2036) in the movie Fantasia was inspired by a poem authored by the 18th-century German author Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, Die Zauberlehrling (in English, The Sorcerer’s Apprentice).

“Let us hope,” wrote Jennifer Jenkins of the Duke University Center for the Study of the Public Domain, “that Disney remembers its own debt to the public domain as Mickey Mouse enters the realm from which it has drawn so heavily!”

Long form articles which explain how something works, or provide context or background information about a current issue or topic.