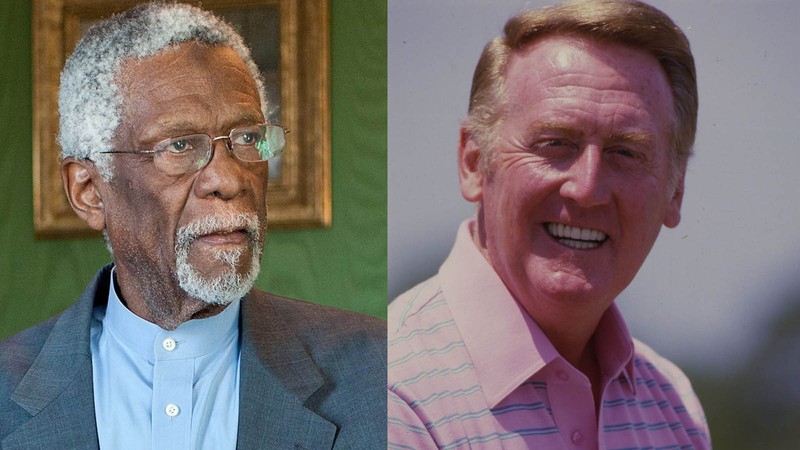

Two towering figures in California sports history have passed away.

Basketball legend Bill Russell (l), and iconic baseball broadcaster Vin Scully (r). Pete Souza / Jayne Kamin / Wikimedia Commons Public Domain / CC. 4.0 Share-Alike License

Two California sports icons died in the past week. One was a native of the Bay Area who built his legend playing for a team on the East Coast. The other, born in the Bronx, N.Y., set new standards for sports broadcasting in a career that took place almost entirely in Southern California.

Vincent Edward “Vin” Scully, who lived to be 94, retired in 2016 after 67 years in the broadcast booth calling Dodger games. The latter 60 years of his career were spent in Los Angeles—when the Dodgers moved west from Brooklyn in 1958 they took Scully, then all of 30 years old, along with them.

Scully had been the lead announcer on Brooklyn Dodgers radio broadcasts since the 1954 season. His predecessor, boss and mentor Red Barber, himself an icon in Brooklyn, abruptly quit the Dodgers and joined the Yankees’ broadcasts after a dispute with Dodgers owner Walter O’Malley following the previous season. Starting with the 1953 World Series, when the Dodgers fell to the Yankees for the second straight year and fourth of the previous seven, Scully was the voice of the Dodgers.

Within just a few years of the move to Los Angeles, as sportswriter Robert Creamer noted in a 1964 profile for Sports Illustrated, Scully had become a major celebrity, his voice “better known to most Los Angelenos than their next-door neighbor's is. … He is stared at in the street. Kids hound him for autographs. Out-of-town visitors at ball games in Dodger Stadium have Scully pointed out to them—as though he were the Empire State Building.”

From 1958 until 1962 the Dodgers played their home games in the cavernous Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum. Their first game there, April 18, 1958, drew 78,672 fans, a baseball record at the time—and there were still almost 20,000 empty seats. The stadium (built in 1921 and home since 1923 to the USC Trojans football team) was so vast that according to a contemporary Los Angeles Times account “the game resembled a pantomime. You couldn’t follow the ball.”

The answer to this problem—Vin Scully.

Fans took to bringing their transistor radios to games, listening live to Scully’s precisely detailed accounts of the action that unfolded on the field somewhere in the distance below them. The practice became an instant tradition, carrying over to the Dodgers' new facility, Dodger Stadium, which opened in 1962 with a relatively modest seating capacity of 56,000. The collective sound of the radios got so loud that Scully could hear himself as he sat in his broadcast booth, and his sound engineers would often need to adjust his microphone levels so his own voice didn’t feed back through his live microphone.

Scully’s voice permeated the Southland. In an era when very few games were televised, Scully’s laid-back style, eschewing rooting or gimmicky “signature” calls, was how most Dodger fans experienced their team’s games. Inviting his listeners to “pull up a chair” at the start of every game (despite the fact that a great many were in their cars, especially for road games which generally started at 4pm Pacific Time) Scully promised an experience of baseball the way it exists in popular mythology—a pastoral, pacifying escape from the worries and rancor of the everyday world.

Bill Russell: Icon of Sports and Social Change

Bill Russell, who passed away at age 88 on July 31, was born on Feb. 12, 1934, in Monroe, Louisiana—the Deep South at the height of the Great Depression. He was forced to fight racism from birth. Both his father and grandfather dodged bullets fired at them for no reason other than that they were Black.

At age nine, Russell and his family—like thousands of other Black people from the South—migrated west to California. They settled in Oakland where Russell would attend McClymonds High School and later, across the bay, the University of San Francisco. It was at USF that Russell began what was easily then, and remains today, the most dominant run of winning in the history of American sports.

With Russell leading the team and playing center, the Dons won back-to-back NCAA national championships in 1955 and 1956 (they haven’t won one since). Then, at the 1956 Melbourne Olympics, Russell led the U.S. Men’s Basketball Team to a gold medal. But Russell’s win streak was just getting started.

He was taken by the St. Louis Hawks with the second overall pick in the 1956 NBA draft, but Boston Celtics Coach Red Auerbach was convinced that Russell was a one-of-a-kind player destined to “change basketball.” Auerbach talked the Hawks into taking two future-Hall of Fame players from the Celtics in exchange for the rights to the USF center. In his rookie season, Russell led the Celtics to their first NBA championship.

After again taking the Celtics to the finals in the following season but coming up short (losing to that same St. Louis team), Russell’s Celtics reeled off eight consecutive championship seasons—the longest title streak in any of the four major American pro sports. (The New York Yankees in baseball and the Montreal Canadiens in the National Hockey League each have a five-title streak, to tie for second.)

Russell still had more championships in him. After the 1966 season Auerbach retired from coaching and named Russell to succeed him, making Russell a player-coach and, more notably, the first Black head coach in American pro sports. After missing the finals in his first season filling both roles, Russell’s Celtics won back-to-back championships in 1968 and 1969.

When he retired at age 34, Russell had played 13 seasons in the NBA and won 11 championships, a performance equalled by no pro athlete before or since. By comparison, Michael Jordan also played 13 seasons (not counting his two-season comeback attempt), and won six championships.

Russell and Civil Rights

His on-court achievements give only a limited picture of Russell’s true stature. In Boston, he was surrounded by supportive teammates, coaches and team ownership, but the same could not be said for the fans. Russell wrote later of the horrific abuse he faced on a daily basis.

“During games people yelled hateful, indecent things: 'Go back to Africa,' 'Baboon,' 'Coon,' 'N****r,’” he wrote in 2020, for the basketball magazine SLAM. His private home was vandalized by racist “fans.” Playing during the Jim Crow era, he was routinely denied service in shops and restaurants, not allowed to stay in the same hotels as white players.

Russell turned his anger at this bigotry into activism. He joined Dr. Martin Luther King’s 1963 March on Washington, and watched King deliver his immortal “I Have a Dream” speech from up close. Also that year, following the assassination of civil rights leader Medgar Evers in Jackson, Mississippi, Russell went to that segregated state to run a racially integrated basketball camp for kids, ignoring death threats and intimidation from members of the Ku Klux Klan.

In 2011, the country’s first Black president, Barack Obama, awarded Bill Russell the Presidential Medal of Freedom.