A new study says that climate change has increased the risk of a cataclysmic flood.

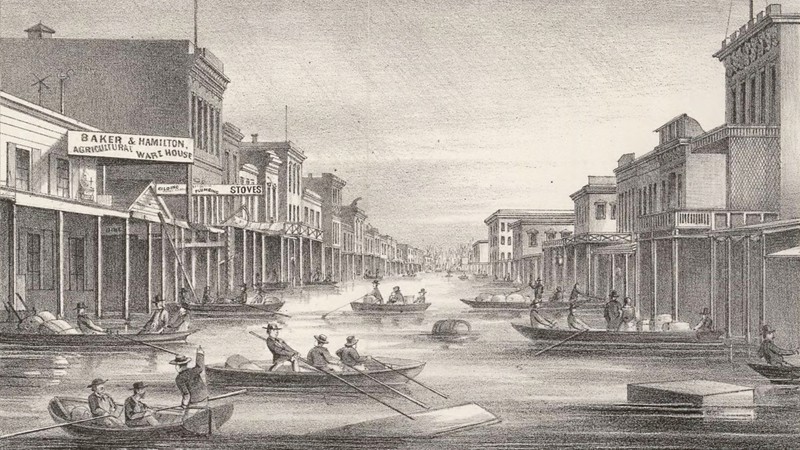

J and K streets in downtown Sacramento during the Great Flood of 1862. Another great flood could be on the way. A. Rosenfield. / Online Archive of California Public Domain

Is California about to be deluged by a massive “megastorm” that will cause flooding of “biblical” proportions? If headlines in media outlets across the country and even the world—including the New York Times, and Britain’s Independent—are correct, the answer is yes, the state is in for rainfall and flooding so overwhelming that the authors of the research paper that sparked the coverage call it an “ArkStorm scenario,” according to the UCLA press release announcing the study.

“Ark” as in “Noah’s Ark,” of course the Old Testament tale of a worldwide flood that wipes out every living thing on the planet, except those gathered by Noah on his wooden boat.

“California, where earthquakes, droughts and wildfires have shaped life for generations, also faces the growing threat of another kind of calamity—a megastorm whose fury would be felt across the entire state,” wrote the New York Times in a Twitter post describing the coming cataclysm.

While a catastrophic storm did, in fact, deluge California more than a century ago, and the risk of a repeat remains, it may not be necessary for drought-stricken Californians to dust off their umbrellas just yet.

Scientists Warn Climate Change Increases Risk

The study co-authored by scientists at UCLA and the National Center for Atmospheric Research and titled “Climate Change is Increasing the Risk of a California Megaflood,” does not offer any concrete predictions as to when an “extreme storm sequence” will hit, or even if it will.

Nonetheless, the researchers offer an ominous warning—climate change has significantly increased the risk that a megaflood-producing event will occur, and largely because Californians have been understandably more worried about getting too little rain, rather than too much, the risk of severe flooding is “broadly underappreciated.”

As global temperature increases, the risk of a catastrophic flooding event also goes up. In fact, according to the study’s co-author Daniel Swain of UCLA, the increased risk produced by climate change has already doubled the chance of a catastrophic storm occurring in any given year from one percent, or 1 in 100, a century ago, to two percent—1 in 50—today.

As the globe continues warming, that likelihood of a megastorm striking California also shoots up. The planet is already 1.1 degrees Celsius higher than it was 150 years ago. If that number goes up by another one degree Celsius, the chance of a megastorm, according to the study, becomes 1 in 30, or 3.3 percent. Under the 2015 Paris Accords, countries have agreed to cut greenhouse emissions enough to keep the temperature from rising above 1.5 degrees Celsius beyond the pre-climate change levels. Whether that goal will actually be met remains in serious doubt, according to a United Nations report.

The Great Flood of 1862

In 1862, just a dozen years after the former Mexican territory joined the United States, a massive storm submerged such large parts of California that it left 4,000 people dead, wiped out 200,000 of the state’s 800,000 cattle, and devastated the economy to the point where state employees went 18 months without pay. Inflation was so bad, due to the sudden destruction of the supply chain, that the price of a dozen eggs shot up to three dollars—about $88 in 2022 cash.

The rainfall began in December of 1861 and continued through late January. The state’s newly elected governor, Leland Stanford, floated to his inauguration in a rowboat where he took the oath of office at a Capitol building that was partly underwater.

The flood was centered in Central California, stretching over 300 miles long and 20 miles wide. The entire population of the state at that time was only about 500,000, meaning that the storm killed one of every 125 state residents. The equivalent today would be a staggering death toll of nearly 315,000.

The study’s authors project that a megaflood today would wreak nearly $1 trillion in damage, due to “widespread, catastrophic flooding… the displacement of millions of people, [and] the long-term closure of critical transportation corridors” among other disasters.

How Bad Would it Really Be?

Unlike an earthquake that strikes with virtually no warning, the hypothetical megastorm would be predictable weeks in advance. That’s because the storm would start as an atmospheric river, a meteorological phenomenon in which warm temperatures cause water to evaporate and gather in the sky. Winds then move the massive flow of moisture until it reaches a land mass.

At that point, the moisture rises further up into the atmosphere where it cools and forms into droplets which fall to the ground in the form of massive rainstorms.

Even with the lengthy period of warning, according to Swain, a lack of planning for a megaflood event would make it impossible to get the 5 million to 10 million Californians living the most hazardous flood zones to safety. At least, that’s what a previous study known as ArkStorm 1.0, conducted in 2010, appeared to show.

The new study, ArkStorm 2.0, hopes to get the state “ahead of the curve.” The state’s preparations should include "letting water out of reservoirs preemptively, allowing water to inundate dedicated floodplains, and diverting water away from population centers in other ways." Other recommendations include stepping up collaborations between the California Office of Emergency Services, the Federal Emergency Management Agency, and other government entities responsible for flood and disaster preparation.

“We got kind of lucky to avoid it in the 20th century,” Swain told the Mercury News. “I would be very surprised to avoid it occurring in the 21st.”