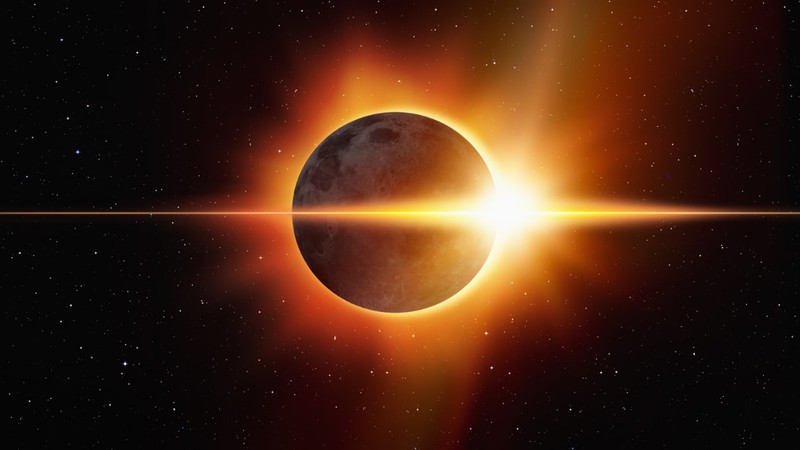

A total solar eclipse can offer a rare opportunity to see stars and planets during the day. Photo illustration by muratart. Elements of this image furnished by NASA

Today's solar eclipse is only possible because of a curious fact: From where we stand here on Earth, the sun and the moon appear to be almost exactly the same size. There is no scientific explanation for this situation. And even though the odds against such a thing are (ahem) astronomical, no one gives it much thought.

We might say it’s just a coincidence. Or we might decide it’s a miracle. Three articles in the Sunday papers talk about Monday’s eclipse in the latter terms.

A piece in the Los Angeles Times suggests a literal miracle, proposing that the eclipse may have the power to bring an end to the partisan wars in America.

The idea may sound far-fetched—until you talk with Paul Piff. The UC Irvine professor of psychology and social behavior has spent the better part of two decades researching what triggers us to set our personal needs aside and shift our focus to the greater good.

One of them, he and other scholars have found, is awe: the feeling you get when you contemplate something that is so vast and so mysterious that it forces you to reevaluate your understanding of the world.

And few things generate awe like watching the moon blot out the sun and plunge a sunny day into eerie darkness. …

“Awe seems to trigger more kind, compassionate and empathic behavior,” he said. “It reminds you of the bigger things that we’re a part of. People talk about eclipses as one of the coolest or most mind-blowing things they’ve ever seen,” Piff said.

One such enthusist is Ryan Milligan, solar physicist at Queens University in Belfast, who has traveled the world to witness 10 total solar eclipses. In an opinion piece for the New York Times on Sunday, he explains why.

A total solar eclipse is not something that you see—it’s something that you experience. You can feel the temperature around you begin to drop by as much as 15 degrees over the 5 to 10 minutes that lead up to the eclipse. The birds and other animals go silent.

‘What I love so much about science is, for me, it is informed worship.’

Ann Druyan, co-creator of the TV series ‘Cosmos’

The light becomes eerie and morphs into a dusky, muted twilight, and you begin to see stark, misplaced shadows abound. A column of darkness in the sky hurtles toward you at over 1000 miles per hour as the moon’s shadow falls neatly over the sun turning day into temporary night—nothing like the calming sunset we take for granted every day. Sometimes a few stars or planets begin to appear faintly in the sky as your eyes get used to the new darkness.

The hair stands up on the back of your neck and the adrenaline kicks in as your brain tries to make sense of what is going on. But it cannot. It has no other point of reference to compare the sensations to. A total eclipse elicits a unique, visceral, primeval feeling.

Brother Guy Consolmagno, director of the Vatican Observatory, is quoted elsewhere in the NYT yesterday referencing the eclipse's “moment of awe.”

“The universe is elegant, it is beautiful, and it’s beautiful in a way that surprises you,” Brother Consolmagno said. “Maybe it’s a sense of what God is like.”

Ann Druyan, a science writer who co-created Cosmos with her husband the late Carl Sagan, agrees that an eclipse has a “mythic, biblical power to it. And it should.”

“What I love so much about science,” Druyan says, “is for me, it is informed worship.”

Indeed, here in California, some of us use the word “universe” exactly the way Brother Consolmagno uses the word “God.” We think of nature—including the stars, planets, mountains and critters—as being sacred. We believe the real world is holy.

And today, in this way of thinking, it’s as though the universe is winking and whispering in the darkness of the day: “Pssst. Check it out. This stuff is magic!”