Daughters of Bilitis, the Mattachine Society, ONE Inc. and many other groundbreaking ‘homophile’ organizations were born in the Golden State.

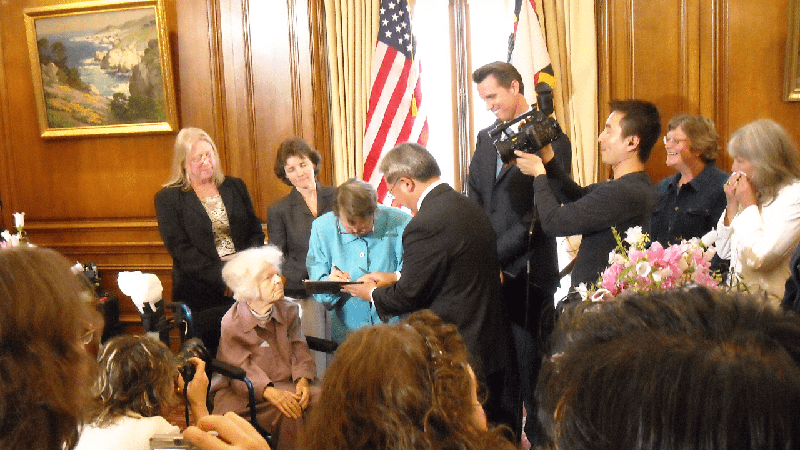

Del Martin and Phyllis Lyon were married twice in San Francisco: in 2004, when Mayor Gavin Newsom began issuing same-sex marriage licenses, and again in 2008 (pictured). Nick Gorton Creative Commons 3.0

Ask your favorite search engine to identify “the birthplace of gay pride,” and right at the top, in the first blurb, you’ll find the Stonewall Riots—the uprising that began June 28, 1969, in a Greenwich Village club and led directly to the creation of Gay Pride Month. But a quick perusal of “Milestones in the American Gay Rights Movement” proves that the Left Coast contributed more than its fair share to the cause.

On its way to becoming the world’s gay mecca, the city of San Francisco (as of 2021, it boasted the highest percentage of LGBT adults of any metro area) became home to many charismatic figures in the 1950s and 1960s who achieved milestones in what was then called the “homophile movement.”

More than 60 organizations existed before 1969, and many of the earliest and most influential organizations and publications devoted to breaking the constraints of gender orthodoxy came into being in San Francisco and Los Angeles. Back in this period, groups had to be secretive due to police harassment; hence, California also was the site of several key protests, including an uprising in 1966 led by transgender women in San Francisco’s Tenderloin District and chronicled in the documentary Screaming Queens: The Riot at Compton’s Cafeteria. And eight years earlier there had been a confrontation at Cooper Do-nut in downtown Los Angeles when bystanders at the gay hangout protested vigorously when five patrons were arrested. Novelist John Rechy, who was on the scene at Cooper Do-nut, later said, “That’s the difference with Stonewall—there were a lot of writers in New York and they wrote about it.”

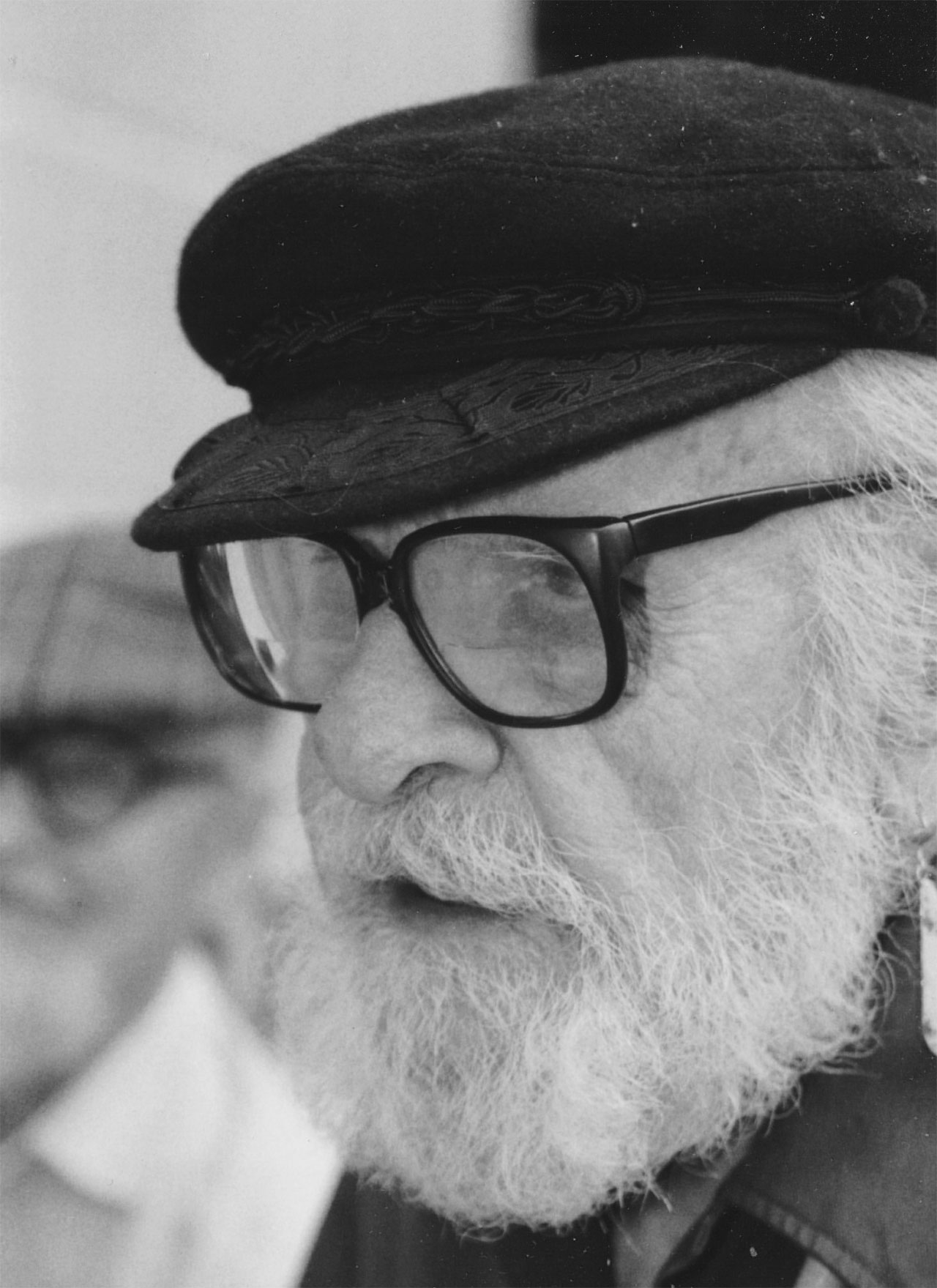

Born in England to a father who was a mining engineer for quintessential imperialist Cecil Rhodes in South Africa and Ghana, Harry Hay traveled far to reach California. In 1950 he founded the Mattachine Society in Los Angeles with Chuck Rowland, Bob Hull, Dale Jennings, Konrad Stevens and John Gruber. The secret network of support groups became “the catalyst for the American gay rights movement,” according to Hay’s obituary in The New York Times. Hay was kicked out of the Mattachine Society over his communist ties and ousted from the Communist Party for his homosexuality. Ultimately, he went on to form the Radical Faeries in 1979 with Don Kilhefner—a group described by biographer Stuart Timmons as “a movement affirming gayness as a form of spiritual calling.” In addition to his longtime relationship with John Burnside, a cofounder of the Radical Faeries, he was also involved with actor Will Geer (who brought him into the Communist Party) and fashion designer Rudi Gernreich.

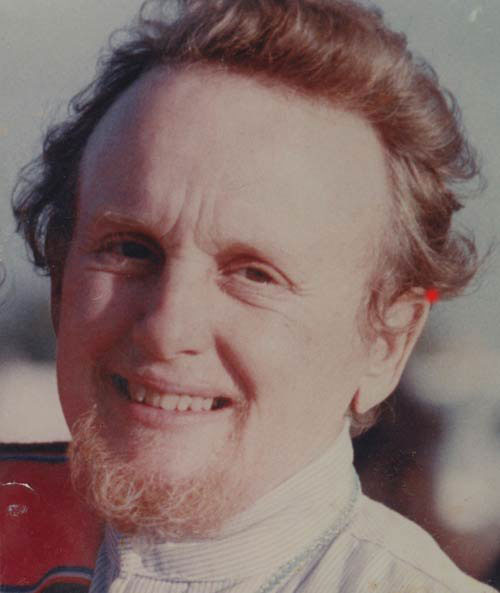

Born in Texas, novelist and playwright Dale Jennings moved to Los Angeles in his late teens to further his career, eventually publishing three novels and writing numerous plays. In 1950, he and his then-boyfriend, Bob Hull, became core members of the Mattachine Society, formed to advocate for gay rights. As The New York Times reported, Jennings became “the infant movement’s first hero” when he was arrested on a sexual solicitation charge and publicly contested it in court in 1952. That same year, he founded ONE Inc. with editor Don Slater and publisher Dorr Legg—the first LGBT organization in the United States to have its own office. (Legg is also known for his involvement in Knights of the Clock, an interracial homophile social club cofounded by his African American lover, Merton Bird.) In 1953 they began publishing ONE Magazine, the nation’s first widly circulated homosexual periodical. That move eventually led to another court case when the United States postmaster in Los Angeles confiscated it as “obscene, lewd, lascivious and filthy.” In 1958, the Supreme Court unanimously reversed lower court rulings and affirmed the magazine's rights.

One of the angel investors behind the aforementioned ONE Inc. was a trans man named Reed Erickson. Born in El Paso, Texas, to a family that owned a lead smelting empire, Erickson got a degree in mechanical engineer, parlayed his inherited assets into a fortune of roughly $40 million, and underwent a female-to-male gender transition in 1963 as a patient of Harry Benjamin, one of the doctors who had assisted in the treatment of trans woman Christine Jorgensen. Erickson devoted his time and fortune to various causes, including the creation of the Harry Benjamin Foundation and the Johns Hopkins University Gender Identity Clinic, as well as various New Age causes—specifically areas of study that were “too new, controversial or imaginative to receive traditionally oriented support.” (Details of Erickson’s extraordinary life—which included three marriages and a pet leopard—can be found in the Transgender Archives compiled by the University of Victoria and the Online Archive of California.)

For half-a-century, Del Martin and Phyllis Lyon shared a life so intertwined that they’re listed as one entry by Wikipedia, the GLBT Historical Society, and the LGBTQ Religious Archives Network. They met in Seattle in the early 1950s and moved to San Francisco, where they were among a group of eight women who founded the Daughters of Bilitis, the first lesbian rights group in the United States. Lyon was editor of the group’s publication, The Ladder, which in 1956 became the first nationally distributed lesiban periodical. (The idea to create Daughters of Bilitis actually came from Rosalie “Rose” Bamberger, a working-class Filipina woman who wanted a safe place to socialize where her lesbian friends wouldn’t be harassed by the police.) Their 55-year relationship included other firsts: They were the first lesbians to join the National Organization for Women, and they helped form the Council on Religion and the Homosexual. In 2004 they obtained the first same-sex marriage license issued by Gavin Newsom, then mayor of San Francisco. They followed up with a second ceremony in 2008, after the state Supreme Court ruled that banning same-sex marriages violated the California Constitution. Just a few weeks later, Martin passed away. The Guardian notes that Lyon said at the time, “I take some solace in knowing we were able to enjoy the ultimate rite of love and commitment before she passed.”

This iconoclast encompassed three identities during her long life. Born in San Francisco as Edythe Eyde, Lisa Ben grew up on an apricot ranch in Santa Clara County and started her professional life quietly, heeding her parents’ desires by taking a secretarial course. In 1945 she broke away from that path and headed to Los Angeles, working as a secretary at the Society of Independent Motion Picture Producers. Once in L.A. she could explore lesbian relationships; out of her desire to meet like-minded women, from 1947 to 1948 she edited and published Vice Versa, acknowledged as the first lesbian publication, while she worked at RKO Studios. In the 1950s, while writing for The Ladder, a magazine published by pioneering lesbian group Daughters of Bilitis, she took the pen name “Lisa Ben” (an anagram of “lesbian”) after her colleagues nixed “Ima Spinster.” Ben continued her publishing adventures, writing and creating illustrations under the name Tigrina. (Read more in a Medium.com article that labels her “America’s most lovably eccentric renaissance woman.”)

Unlike many of California’s early champions of gay rights, José Sarria didn’t move from elsewhere seeking liberation. Born to an upper-class single mother who fled Colombia’s Thousand Days War and ended up in San Francisco, Sarria is inextricably linked with many nascent gay organizations, and is widely believed to be the first openly gay person to run for public office in the United States. That campaign came in 1961, when Sarria came in ninth in a wide field, but though he didn’t win, he did demonstrate the power of the gay vote. “From that day on, there’s never been a politician in San Francisco, not even a dogcatcher, that did not go and talk to the gay community,” he’s quoted as saying in a New York Times obituary. Sarria is also known for his campy opera satires—performed at the Black Cat Cafe gay bar in North Beach—and his involvement in founding the following organizations: the League for Civil Education (1960), which fought against laws that prohibited the sale of alcohol to gay people; the Society for Individual Rights (1963), a more broad-based advocacy group serving the gay community; and, most colorfully, the Imperial Court de San Francisco (1965), which has since grown into the International Court System, with chapters in the United States, Canada and Mexico.

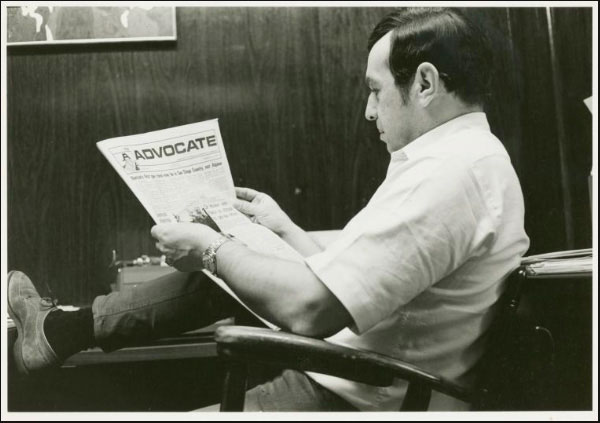

The Advocate, one of the most prominent gay publications in the United States, got its start after Richard Mitch (aka Dick Michaels) was galvanized by police harassment and arrests in 1966 at the Black Cat Tavern, a Los Angeles gay bar. Along with other members of the L.A.-based group Personal Rights in Defense and Education (PRIDE)—Mitch and his boyfriend, Bill Rau (aka Bill Rand), along with Aristide Laurent, and Sam Allen (also referred to as Sam Winston—published the first issue of The Advocate in 1967. According to Encyclopedia.com, the goal was to create “a written record for the gay community of what was happening and impacting their world,” and the first copy of what was then called the Los Angeles Advocate could be purchased for 25 cents in gay bars and shops. In 1974 the publication was sold to San Francisco investment banker David B. Goodstein, who moved the paper to the Bay Area and transformed it into a national news magazine. Online information on the founders of the Advocate is scarce (we were unable to find Mitch and Rau’s birth years), due partly to their use of pseudonyms, but one can hear Mitch’s voice on this audio recording. “The paper grew out of the interest of the people who got ahold of it,” Mitch says, explaining that once it got national distribution, he began to notice civil rights activity spreading to other parts of the country, particularly on campuses. “The Advocate worked as a catalyst,” he asserts.

Born in New York, Jim Foster ended up in San Francisco shortly after a dishonorable discharge from the military in 1959. His involvement in what was then called the homophile movement began in 1964, when he cofounded the Society for Individual Rights. Writing for Black Sheets magazine in 1998, Bill Brent opined that SIR represented a “new breed” of organization that was “liberationist” as opposed to “assimilationist.” Brent writes, “It was also more democratic and inclusive, and this new style would become a model for gay political organizations to follow.” In 1971 Foster joined forces with Del Martin and Phyllis Lyon (see above) to create the Alice B. Toklas Memorial Democratic Club, named after the famed Oakland resident. The club supported presidential candidate George McGovern’s campaign, and on July 14, 1972, Foster spoke at the Democratic National Convention—the first openly gay delegate to do so—advocating for a gay rights plank.

Raised as a Southern Baptist in Florida, Troy Perry found a new path to a spiritual life in California. First he married a preacher’s daughter and joined a Pentecostal church—but he couldn’t deny his attraction to men. After his five-year marriage and a stint in the Army ended, Perry found a new calling: to create a church for the queer community. In 1968 he founded the Metropolitan Community Church out of his living room in Los Angeles. According to the LGBTQ History Project, by 1971 the MCC had its own church that accommodated 1,000 people, and has grown to have more than 200 member congregations in 37 countries. Perry also made a contribution to the fight for gay marriage when he wed Phillip Ray De Blieck in Toronto in 2003 and filed suit against the State of California, seeking recognition of the marriage. But his involvement in the issue began much earlier, when his church performed its first same-sex marriage in 1968. Now retired, Perry is still an active voice for equality on social media.

Article exploring songs, books, movies and other works from art and culture which feature our beautiful state.