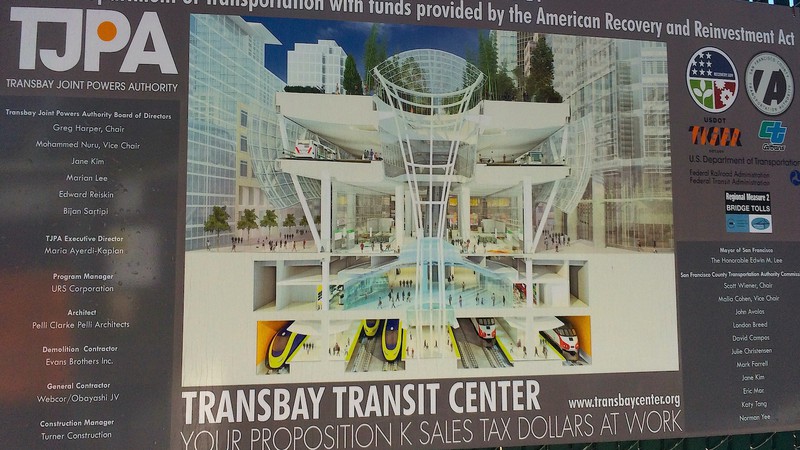

Joint Powers Authorities are important government agencies with little public accountability. Peter Simpsons / Wikimedia Commons C.C. 4.0 License

What if there were a government entity that had the power to levy taxes, to accumulate debt, to enter into contracts, acquire land, construct buildings, and a wide range of other government functions — all without answering to voters, or even to their elected representatives? In fact, in many cases, citizens may not even know that this entity exists.

Sounds bad, right? But in California, not only does exactly this type of government agency exist right now, it’s been around for 100 years. And it’s not just a single entity. There are hundreds, maybe thousands of them in cities and counties throughout the state.

Known as Joint Powers Authorities, this type of entity is not necessarily as suspicious as it sounds and in most cases, JPAs serve a legitimate purpose. But as a 2021 Nevada County Grand Jury report titled “Joint Powers Authorities: What You Need to Know” found, JPAs under the law are subject to little if any oversight or accountability, leaving them open to “possible misuses and abuses.”

Perhaps the most significant problem, the Nevada County Grand Jury found, is the lack of oversight. Civil grand juries are the only public investigative bodies with legal authority to investigate JPAs, and while every California county maintains one, the civil grand jury’s role is only as a watchdog. It has no power to force a JPA or any other agency to correct problems and issues it finds.

A 100-Year Old Potential for Abuse

So what is a Joint Powers Authority? According to a 2007 report by the state Senate Local Government Committee, “joint powers are exercised when the public officials of two or more agencies agree to create another legal entity or establish a joint approach to work on a common problem, fund a project, or act as a representative body for a specific activity.”

The first JPA in California, back in 1921, was created between the city of San Francisco and Alameda County, with the singular purpose of constructing a sanitarium for patients suffering from tuberculosis, a disease then epidemic in San Francisco.

The two Bay Area governments were permitted to work together in an early form of Joint Powers Authority thanks to a 1921 law authored by San Mateo State Senator M.B. Johnson, allowing any two city or county governments to act as a single government, albeit only for a specific purpose.

Not everyone was thrilled with the creation of this new type of potentially quite powerful entity. A challenge to the law made it all the way to the state Supreme Court. But in 1923, the court upheld the JPA law.

The Ever-Expanding Scope of Joint Powers

After that, there was no stopping the expansion of JPAs. In the 1940s, the state legislature broadened the law to allow not just city and county governments to form JPAs, but special districts, such as water and fire districts, as well.

A few years later, another piece of legislation cleared the way for state governments and even federal government entities to create JPAs with cities, counties, and special districts. In 1947, the California legislature decided to allow separate joint powers agencies to govern the functions of JPAs, independently of the governing bodies of each member entity.

And in 1949, all of those previous JPA laws were codified into a single piece of state legislation that also granted JPAs the ability to take on debt and sell bonds, in order fund public construction projects.

As JPAs have proliferated in recent years, they have been formed to address issues ranging from road construction and airport expansion, to habitat conservation and groundwater management. There are two main ways of structuring a JPA, as described by both the Nevada County and Orange County grand juries: “vertical” and “horizontal.” The latter type of JPA involves two or more separate governments—a city and a county, for example, or two cities—with a need or problem in common. Building a road that runs through both member cities in a JPA would be one example of a common interest.

The original California JPA was created because in the 1920s, the damp, chilly climate in San Francisco was thought to be harmful for people trying to recover from tuberculosis. By working together with Alameda County, the city was able to house TB patients in the neighboring county with its drier, more temperate weather.

Horizontal JPAs have some degree of accountability, because if one of the member governments becomes dissatisfied or perceives some sort of malfeasance, it can simply withdraw from the JPA, which would likely dissolve it.

Taxpayers Can be Left Holding the Bag for JPA Debt

Vertical JPAs are where most of the potential problems are found. In a vertical JPA, two or more agencies within the same organization join forces. Until 2012 when California’s local redevelopment agencies were dissolved it became common for a city to form a JPA with its own RDA. That way, the city could issue bonds and take on debt for redevelopment efforts without voter approval, simply by using the JPA as the bond-issuing entity.

In a 2015 investigation in Orange County, the Civil Grand Jury warned that vertical JPAs could be used the way businesses use shell companies to conceal shady financial dealings. “This organizational structure has the potential to cloak funds and accountability of those funds,” the OC Grand Jury warned, adding that “the opaque, layered structure gives the government the ability to obfuscate financial transactions within the parent organization and hence from the taxpayers.”

The Grand Jury in Orange County said that “the use of a JPA to legally by-pass the voting rights of the taxpayers or obfuscate the financial transaction’s real cost is an unacceptable situation for its citizens.”

In Contra Costa County, the Civil Grand Jury in a 2018 report found that each of the county’s 19 incorporated cities reported belonging to at least one JPA, totaling 157. But with multiple cities belonging to individual JPAs, the actual number of JPAs in Contra Costa County at the time was 66. The grand jury report also found that the 19 cities in those JPAs had issued a total of $1.5 billion in bonds — without any mechanism for keeping tabs on the debt rolled up by the JPAs, and that’s a problem. By issuing bonds through JPAs without oversight or voter approval, cities can take on more debt than would otherwise be legally allowed, the Contra Costa Grand Jury noted.

Who could be left picking up the tab for that excessive debt? The answer according to all of the grand jury reports is the same — the local taxpayers.

JPAs Can Set Examples of Governments Working Together

Why, then, do JPA’s exist? There’s a long list of good reasons.

“JPAs exist for many reasons, whether it’s to expand a regional wastewater treatment plant, provide public safety planning, set up an emergency dispatch center, or finance a new county jail,” wrote the state Senate Local Government Committee, in a 2007 report. “By sharing resources and combining services, the member agencies—and their taxpayers—save time and money.”

In its own report on the subject, the League of California Cities noted that, “In this age of regionalism, limited resources available to local governments to carry out their missions, and ever increasing unfunded mandates from the state and federal governments, joint powers authorities have become a cost effective means by which local governments can carry out necessary business.”

At their best, JPAs can serve as an example of governments or agencies with competing interests working in unison to achieve common goals for the public good. But as the county grand jury reports have warned, the “opaque” structure, particularly of vertical JPAs, is a scandal waiting to happen.

“At their worst,” the Nevada County Grand Jury declared, “they can be sinkholes for cost overruns and cronyism, lack transparency, and evade oversight by citizens and officials.”

Long form articles which explain how something works, or provide context or background information about a current issue or topic.