The Bakersfield Republican’s rapid rise to power began with a winning lottery ticket.

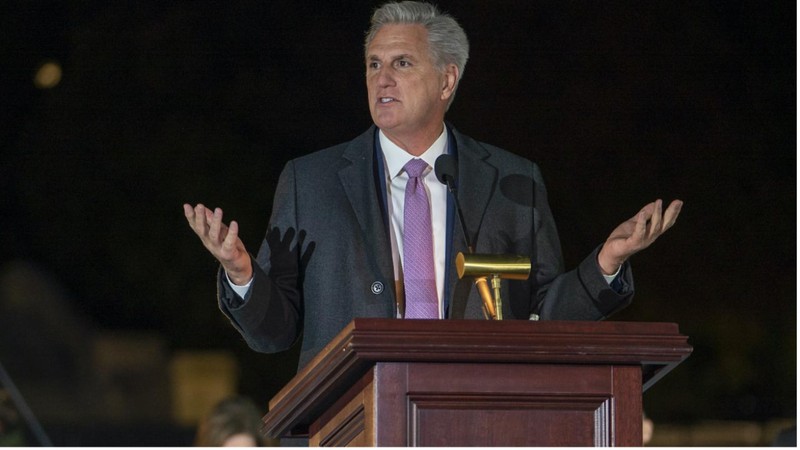

Kevin McCarthy, the Bakersfield Republican whose fall from power was even more rapid than his rise, gave a farewell speech on Dec. 14.

Many conservatives hold to the tenet that success is achieved through hard work and dedication. So how did California’s most prominent conservative politician launch his remarkably speedy path to the top? Kevin McCarthy won the lottery.

McCarthy’s tale is one of a consummate political glad-hander, a man who surfed the wave of the backslapping circuit all the way to a spot just two heartbeats away from the United States presidency.

He started with a stroke of luck, and it wasn’t the last bit of luck he’d have in his career. But it could be argued that Kevin McCarthy’s rapid political rise and fall is the story of a man who made his own luck by making sure he always had the best chance he could of being in the right place at the right time.

McCarthy’s tale is one of a consummate political glad-hander, a man who surfed the wave of the backslapping circuit all the way to a spot just two heartbeats away from the United States presidency—without ever creating any noteworthy legislation or effecting significant political change of any kind.

Lightning Rise and Thunderous Fall

McCarthy was ousted as United States House Speaker on Oct. 3, 2023, voted out by members of his own party after serving just 270 days in the job—the shortest speaker’s term since before the 20th century and third-shortest in American history. Two quick months later, he published an op-ed in the Wall Street Journal announcing that his political career was over. He would, he said, resign from Congress a full year before the end of his elected term.

“He was a hustler, a go-getter. He was an entrepreneurial type when the rest of us were going to college.”

NICK BIKAKIS, FRIEND OF KEVIN McCARTHY

But the Bakersfield native’s rise was, in many ways, equally remarkable. Elected to the state assembly in 2002, Kevin Owen McCarthy at the age of 38 was named Republican leader (he preferred that term to “minority leader”) just a year later—the first time a first-term Assemblymember has risen to the leadership of his party’s caucus. A mere five years after that, he ran for the U.S. Congress and won, taking over the seat vacated by his political mentor, Bill Thomas. McCarthy had earlier served 15 years as a congressional staffer for Thomas.

McCarthy’s Origin Story: Kevin O’s Deli

In 1985, 22 years before he was elected to the House, McCarthy—at the time a 20-year-old student at Cal State Bakersfield—walked into a local store and bought a scratch-off ticket. It was only the second day that California sold lottery tickets. When he was done scratching, the young McCarthy was $5,000 richer.

Already a hustler who made money buying cars at auction in Los Angeles then “flipping” them in his hometown of Bakersfield using a borrowed car dealers’ license—a scheme which he later acknowledged may not have been strictly legal—McCarthy added 30 percent to his lottery winnings in the stock market, then used his newfound cash to open a deli counter in a corner of a frozen yogurt shop owned by his uncle.

“He was a hustler, a go-getter,” his friend Nick Bikakis told the Washington Post. “He was an entrepreneurial type when the rest of us were going to college.”

McCarthy says that after operating the deli counter, which he called “Kevin O’s,” profitably for a year, he used his earnings to go back to college at Cal State Bakersfield—which charged no tuition at the time with student fees limited to $338 per year. McCarthy lived at home during his college years, so he had minimal living expenses as well.

The deli story over the years became a staple of McCarthy’s interviews and speeches, designed to show his roots as a self-starting entrepreneur.

“I tell the story so people realize I don’t give up on things,” McCarthy told the Post in 2018. “ I tell the story so they realize I am willing to take a risk. So they will look at you, not just, ‘Oh, you are a member of Congress.’ ”

Fair enough. But the facts of McCarthy’s career show that running the deli counter was the last job in the private sector he ever had.

A Congressional Lifer

Two years before he graduated from Cal State Bakersfield with a bachelor’s degree, McCarthy made his way into the office of Bill Thomas, the Republican House rep from Bakersfield, talking his way into a role as an unpaid intern. Thomas later hired McCarthy as a full-time staff member, a position he held for 15 years, until 2002, when he won his seat in the California Assembly.

It should be noted that McCarthy, in his 16 years in the House, served on one committee, the House Financial Services Committee, from 2011 to 2014.

The Assembly race was McCarthy’s second election campaign and second victory. In 2000 he won a seat on the Kern Community College Board of Trustees. He also chaired the California Young Republicans, and from 1999 to 2001, the Young Republican National Federation. But as an assembly member, McCarthy set to work immediately on what he was best at—making friends.

“Nobody didn’t like Kevin,” Jim Brulte, a leading state Senate Republican who later became state party chair—and who once took the upstart McCarthy to Washington and introduced him as a future Speaker of the House—told the Associated Press. “Even people who were opposed to him liked him.”

In 2006, as McCarthy was finishing just his second term in the Assembly, Thomas—who was about to lose his seat as chair of the powerful House Ways and Means Committee—announced his retirement from Congress. McCarthy ran for his seat and once again, won.

But where Thomas had been considered a somewhat moderate Republican and serious legislator with accomplishments ranging from health care to tax cuts to protecting worker pension funds, McCarthy appeared to have very little interest in policy or legislation. He had his sights set right away on the House’s top job.

“That was the only job he ever wanted,” Thomas told a Bakersfield TV station after McCarthy’s ouster from the Speaker’s office. “He didn’t serve on committees, where you could become, to a degree, not an expert, but at least very knowledgeable, where you have a bankable skill… That was all he ever wanted.”

It should be noted that McCarthy, in his 16 years in the House, served on one committee, the House Financial Services Committee, from 2011 to 2014.

“My Kevin”

In 2010, McCarthy, then age 45, and two other Republican leaders—Paul Ryan of Wisconsin, who was 40, and Virginia’s Eric Cantor, age 47—authored a book titled Young Guns: A New Generation of Conservative Leadership.

McCarthy outlasted his fellow “Young Guns” largely because he relied on his talent for ingratiating himself to the right allies to become an early backer of Trump.

The “Young Guns” obviously referred to themselves. And at that time, the trio were indeed treated by the media and Washington insiders as the rising young (in Washington, D.C., terms) stars of the Republican Party, who promised to take the tired, old GOP—which just two years earlier had suffered stunning electoral defeats in the House, Senate and, with the election of Barack Obama, the White House—in an exciting, fresh new direction.

Just four years later Cantor was out of Congress, the first sitting House Majority Leader ever to lose reelection to his seat. Ryan, after a failed bid for vice president as Mitt Romney’s 2012 running mate, assumed the speaker’s role in 2016—only to sheepishly retire from Congress two years later after a series of humiliations at the hands of Donald Trump and an election in which Democrats took back the House, handing the speakership back to San Francisco’s Nancy Pelosi.

McCarthy outlasted his fellow “Young Guns” largely because he relied on his talent for ingratiating himself to the right allies to become an early backer of Trump.

The two started off with a contentious relationship. McCarthy made his first run at the Speaker’s post in 2015, and as House Majority Leader, he quickly became the favorite to succeed John Boehner. And then, in October of that year, McCarthy suddenly withdrew from consideration, apparently lacking the full 218 votes necessary to win the post.

Trump, then just a few months into his presidential campaign, immediately took “credit” for blocking McCarthy’s bid.

“You know Kevin McCarthy is out, you know that? Right?” Trump said in a Las Vegas campaign speech. “They are giving me a lot of credit for that because I said you really need somebody very, very, tough, and very smart, you know smart goes with tough, not just tough.”

Trump’s clear implication that he was not “smart” appeared not to bother McCarthy greatly, however. Or if it did, any offense he may have taken was outweighed by his instinct for advancing himself politically. In May of 2016, once it had become clear that Trump would be the Republican presidential nominee, McCarthy volunteered to act as a delegate for Trump at the party’s nominating convention.

As tensions continued to simmer between Trump and Ryan in the early months of Trump’s presidency, McCarthy proved himself a loyal servant, Trump’s reliable confidant in the House. A few weeks into his term, Trump affectionately dubbed McCarthy “my Kevin.”

McCarthy Turns on Trump, then Quickly Turns Right Back

McCarthy managed to stay largely in the mercurial Trump’s good graces until Jan. 6, 2021. Trump, of course, lost the 2020 presidential election to Democrat Joe Biden, but bizarrely, dangerously and falsely maintained that the election was “rigged” and that he, in fact, won. The violent attack on the Capitol on Jan. 6, which followed an incendiary speech by the soon-to-be-former president and resulted in seven deaths, briefly caused a rift between McCarthy and Trump. During the Capitol insurrection, McCarthy reached Trump via phone and the two got into an “expletive filled argument,” according to an NBC News report, as McCarthy allegedly pressed Trump to call off his supporters.

A few days later, McCarthy said that Trump “holds responsibility for what happened.” But three weeks after the attack, about a week after Trump left office, McCarthy visited the former president at his Mar-a-Lago estate in Palm Beach, Florida.

According to former Wyoming Republican House Rep Liz Cheney, McCarthy later claimed that his visit was not an attempt to show fealty to Trump, but instead it was a kind of wellness check. McCarthy told Cheney that Trump was “depressed” and “not eating,” which is what prompted his pilgrimage to Palm Beach.

Whatever the reason, when McCarthy was facing a House vote to remove him from the speakership, Trump stood on the sidelines, declining to say a word on his behalf.

The End, and the Epilogue, for Kevin McCarthy

When McCarthy was elected Speaker in January 2023, it took 15 ballots, and he made a series of concessions to his Republican opponents. One of those concessions was to allow a rule change under which a single House member could force a vote to “vacate” the speaker’s job—in other words, to fire McCarthy.

That’s exactly what happened. On Oct. 3, Florida Republican Matt Gaetz—another Trump loyalist and member of the House Republicans’ far-right wing—filed the “motion to vacate,” forcing the vote. When eight of those far-right Republicans, including Gaetz, voted against him along with all 208 Democrats, Kevin McCarthy lost the only job he ever wanted.

Gaetz had been threatening to file the motion for weeks, but what finally triggered him was McCarthy’s deal with Democrats on a financing bill that would avert a government shutdown—an actual legislative achievement that ultimately ended a career based on his ability to create personal relationships.

In an exit interview with the political news site The Hill two months later, McCarthy offered his thoughts about Gaetz, calling him “psychotic,” and adding, “people study that type of crazy mind, right? Mainly the FBI.”

What’s next? McCarthy in December told the political news site Axios that he plans to work on behalf of artificial intelligence development, acting as a liaison between the tech world and Washington.

On Dec. 14, McCarthy delivered his final speech on the floor of the House.

“I knew the day we decided to make sure to choose to pay our troops while war was breaking out, instead of shutting down, was the right decision,” McCarthy said in the speech. “I also knew a few would make a motion. Somehow they disagreed with that decision ... I would do it all again.”

In his farewell address, McCarthy also declared that he “loved every single day” of his time in Congress.

Long form articles which explain how something works, or provide context or background information about a current issue or topic.