The battle between public and private ownership is at the heart of Monterey County’s water system.

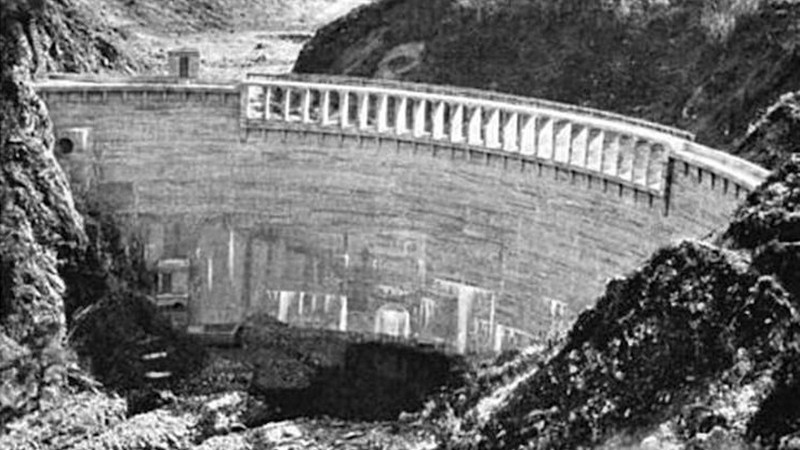

The San Clemente dam on the Carmel River, built by industrialist and inventor Samuel Morse. J.A. Wilcox / Wikimedia Commons Public Domain

Who owns the water? Should the public own it, or should private corporations control this most essential resource? The public-private conflict has been at the center of Monterey County’s effort to bring water to its people for well over a century—a conflict that continues even today as the county’s largest public water district battles to buy out the private entity that owns and operates the system that delivers water to residents within the district’s boundaries.

And that battle is just the latest of several attempts by the district to take over the privately owned water system, dating back almost nine decades. Private ownership of Monterey peninsula water, however, goes back much longer than that.

Rewinding to 1770, a full 80 years before Monterey County was incorporated, Spanish missionary Junípero Serra ordered slaves to dig a channel that would let water flow to his mission from the Carmel River. A century later, the water system was no longer driven by slavery, but had not progressed greatly in sophistication—at least according to the description offered by Scottish novelist and world traveler Robert Louis Stevenson, who stayed in Monterey in 1879 to recover his failing health.

“All the windmills in Monterey are whirling and creaking and filling their cisterns with the brackish water of the sands,” the Treasure Island author wrote in an account of his Monterey stay.

Two years after Stevenson’s visit to Monterey, millionaire tycoon and Southern Pacific Railroad president Charles Crocker acquired the rights with his partners in a holding company to construct a 23-mile water main from the river to the company’s new development project, the Hotel Del Monte. (This luxury resort operated from 1880 to 1942, until the land was leased to the U.S. Navy for the Naval War College.)

After another two years, Crocker’s Pacific Improvement Company backed construction of the Carmel River Dam, which was known at the time as the “Chinese Dam,” because Chinese immigrant workers had labored around the clock to build the dam, which supplied about 400 acre-feet of water to the lavish hotel. (One acre-foot equals 326,000 gallons of water.)

The city of Monterey soon connected to the company’s water system, which became known as the Monterey County Water Works, but remained in the hands of private shareholders. More than a century later, that water delivery system remains the property of a private company. But a public agency, the Monterey Peninsula Water Management District—the largest of six special water districts which manage water delivery in the county—manages and ultimately controls water policy for businesses and county residents on the Monterey Peninsula, as well as the city of Seaside and parts of Carmel Valley.

The actual delivery of water to those residents and businesses is handled by California American Water, or Cal Am, whose parent company, New Jersey-based American Water Works, bought the peninsula water system in 1965. The out-of-state company then created the Cal Am subsidiary to manage its water holdings in Monterey County as well several other counties up and down the state, including Sonoma, Los Angeles, Sacramento, San Diego and Ventura.

American Water Works purchased the Monterey Peninsula water system from the California Water and Telephone Company (CWT). How did the peninsula’s water system end up in the hands of a telephone company?

The answer goes back to one Chester H. Loveland, a former member of the California Railroad Commission (now known as the California Public Utilities Commission) who had left public service to start his own engineering firm, which soon became Western Utilities Corporation, and which in turn created its CWT subsidiary.

In 1930 Loveland bought the system and its attendant water rights from its previous private owner, Samuel F.B. Morse, an entrepreneur and tech industry giant of his day. Best known for his invention of the telegraph (the famous code used for telegraphic communication is named after him), Morse in 1919 bought out Pacific Improvement Company’s interests in the Del Monte Hotel and its connected water system which by then served much of Monterey.

Morse funded the building of a second dam on the Carmel River, the San Clemente Dam (pictured above, circa 1921). Then he sold out to Loveland’s company with the agreement that CWT would supply water to the Del Monte properties without substantially raising the price for the next 50 years.

Loveland quickly broke that pledge, raising water rates on Monterey customers just one year later. That led to a local push to take over the water system and make it a public asset. The movement was strong enough to put the public buyout question on the ballot in 1935—where it was roundly defeated by better than a two-to-one margin.

After CWT hiked rates again in 1952—by 25 percent, after the CPUC nixed a requested 46 percent increase—another movement for a public takeover took hold. This time, in 1958, voters gave a thumbs up to forming a new Monterey Peninsula Water District that would take over the CWT holdings plus those of another company in Seaside, East Monterey Water Service Company.

The companies didn’t want to sell, however, and stalled by forcing the district to petition the CPUC to approve a fair price. The district finally got its price and put a bond measure on the ballot in 1965. This time voters—wait for it—said no.

The same voters who less than a decade earlier approved a public water takeover now put the kibosh on the very effort they had approved. The water district folded, and both private companies began rationing water and deferring maintenance. That’s when American Water Works bought out both companies, consolidating them under the Cal Am label.

The buyout did not halt public efforts to take over the peninsula’s water system. In 1978, an act of the state legislature created the Monterey Peninsula Water Management District (MPWMD) for two purposes—to bring Cal Am’s chronic over-drawing of water from the Carmel River under control, and to have an agency in place for the day when the public is able to take over the water company’s system at last.

Since then, the MPWMD has overseen Cal Am’s operations, but in 2018 voters passed Measure J, which required the district to buy out Cal Am following completion of a study that showed the buyout to be financially “feasible.”

That study itself has been a major obstacle to the takeover. The district study determined that the value of Cal Am’s operation was just over $500 million. Cal Am says that it’s worth twice that—$1 billion. The county’s Local Agency Formation Commission (LAFCO) has also thrown a wrench into the water works. LAFCO must approve all changes to the boundaries of any city or special district. If it takes over Cal Am’s system, the MPWMD would need to expand by 139 acres, territory now served by Cal Am that falls outside of current MPWMD boundaries.

The Monterey County LAFCO has dragged its feet, with the commissioners in October of 2021 demanding that the district perform—and pay for—an entirely new feasibility study, leading MPWMD General Manager Dave Stodlt to grumble that “my gut instinct is they didn’t read the report.” LAFCO now won’t consider the matter until at least December 2021, and according to coverage by the Monterey County Weekly LAFCO staff say until there’s a ruling on a lawsuit by the Monterey Peninsula Taxpayers Association against MPWMD, the district’s finances are not stable.

Perhaps fortunately for the city of Marina, its water district—aptly known as the Marina Coast Water District—does not have the same public-private conflict. Founded in 1960, the district owns and manages water delivery for that city. The district also provides water service for the Ord community, the site of a now-closed United States Army base, Fort Ord. In 2021, the Marina Coast Water District began proceedings to annex the Ord territory and make it part of the district.

The Marina district serves 9,416 connections, making it the second-largest water district in the county behind the MPWMD’s 37,706 connections through Cal Am, according to the state’s Safe Drinking Water Information System.

Monterey County is also served by two water districts that overlap with and are controlled by other counties: Pajaro Valley Water Management Agency, in Santa Cruz County, and Aromas Water District, which is operated by San Benito County. Two other, much smaller water districts also serve largely rural areas in Monterey County. Those are San Ardo and San Lucas water districts, with 161 and 92 connections, respectively. All of San Ardo’s water comes from a single well.

Castroville, Ocean View, Pajaro-Sunny Mesa, and Santa Lucia community services districts provide water services to those communities, as does Pebble Beach Community Services District, which has also acted as the local government of Pebble Beach since 1982.

Long form articles which explain how something works, or provide context or background information about a current issue or topic.