A once-groundbreaking nonprofit working with chronically homeless people in California’s capital closed and filed for bankruptcy in 2023. Here’s what happened.

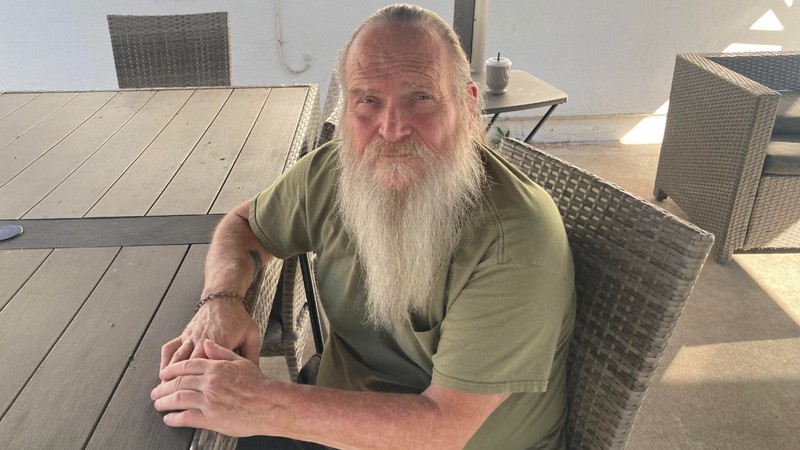

Mark Oden was among the thousands of chronically homeless people helped by Sacramento Self-Help Housing prior to the organization’s failure. Graham Womack

Rick Shrader is nervous. Shrader, 61, lives in permanent supportive housing managed by SHELTER, Inc. in south Sacramento. There’s still a sign posted in front of his apartment for former manager, Sacramento Self-Help Housing (SSHH). That organization, which used to house hundreds of formerly homeless people like Shrader annually, shut its doors and went bankrupt last spring after years of financial issues.

Months later, there’s still fallout. And people like Shrader, who said he left a life of homelessness and drugs to come to SSHH five years ago, are somehow still facing potential displacement.

“I don’t even know if I have hope for the future,” Shrader said. “I thought this was the future.”

This is the first in an investigative series drawing on interviews with dozens of people close to SSHH and an extensive review of public records. This is a story of well-intentioned leadership and board members at SSHH who eventually found themselves over their heads and watched their problems compound. It’s a story of serious financial missteps.

This series also examines how much oversight Sacramento County provided as SSHH was sputtering, and what happened to people SSHH once housed. It includes extensive commentary from SSHH’s founding chief executive officer, John Foley, in his first public interviews since his board put him on leave in January 2023, effectively ending his job.

Work by county officials and other organizations last spring appears to have prevented hundreds of people from going homeless due to SSHH’s failure, as was originally feared. Still, an unknowable number of people likely became homeless due to SSHH’s collapse, based on accounts from several sources.

‘If we were 7-Eleven, we would have shut the doors immediately. We would’ve unplugged the Slurpee machine. Just wrap it up. We didn’t. Because we housed at that time 700 people, we employed 180 people and we owed a lot of people in town money.’

ETHAN EVANS, FORMER SSHH BOARD CHAIR

In general, it is difficult to find precise statistics about people experiencing homelessness. The U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) mandates biennial point-in-time counts of unsheltered individuals, and these counts are notoriously inaccurate. Beyond this, not everyone who winds up homeless will go through an eviction process or have some other official record that confirms what happened to their housing.

Former SSHH board chairman Ted Cobb says most of the organization's clients found other housing after the organization folded.

“I would say that 80, 85 or 90 percent of the people in Self-Help Housing’s programs were able to transition into something else and did not end up on the streets,” Cobb said in late September. “Certainly a few people did. There’s no doubt about that.”

Navigating a Collapse

Ethan Evans, an assistant professor at California State University, Sacramento, became board chairman of Sacramento Self-Help Housing on Jan. 9, 2023, the day Foley was put on leave. That same day, Cobb, who is Foley’s cousin, stepped down as chairman after more than a decade, though he kept a seat on the board.

“If we were 7-Eleven, we would have shut the doors immediately,” Evans said. “We would’ve unplugged the Slurpee machine. We would’ve sent our employees home. That would be it. Just wrap it up. We didn’t. Because we housed at that time 700 people, we employed 180 people and we owed a lot of people in town money. And over the course of two months, we tried to figure out: Is this salvageable?”

One of SSHH’s core offerings was what’s known as scattered-site shelter. This is a type of shared housing SSHH helped to pioneer locally, typically placing a small number of formerly homeless people into a house where they could live and receive services. Each house typically had a monitor, often a person who’d been formerly homeless themselves.

SSHH contracted with Sacramento County for 160 beds of scattered-site shelter, among a series of contracts the two organizations had over the years.

In better times, SSHH helped thousands of people get housing. It’s what Jeremy Baird said he’s most proud of from his tenure. Baird began working for SSHH in 2013 when he was just out of college. He was its final interim CEO in its last two months and is now program manager for City Net, the county’s new scattered-site shelter vendor. “As I’m out and about in the community, I see people that come up to me and recognize me and thank me for the work that we did for them,” Baird said.

In recent years, though, SSHH’s operations began to fracture.

On March 28 of last year, Chevon Kothari, deputy county executive for social services told the Sacramento County Board of Supervisors that the county would be making a break with SSHH.

County Supervisor Patrick Kennedy, who served on SSHH’s board in the mid-2000s, said in June that the county was “working with the landlords who weren’t paid for a while to help them become whole.”

“Due to significant financial and management concerns that we have had with SSHH for some time now, the county has made a decision not to renew our contracts for the scattered-site housing program after our contract with SSHH ends on June 30, 2023,” Kothari, who declined to be interviewed, told the board. “We have not terminated the contract, but will just not be renewing it.”

At the end of 2022, a contract that SSHH had with the county for property related tenancy services, or PRTS, had also ended.

SSHH didn’t work exclusively with Sacramento County. The organization also provided permanent supportive housing, funded by three grants from HUD through its local passthrough, Sacramento Steps Forward. SSHH also had contracts with San Joaquin County and the cities of Elk Grove and Rancho Cordova.

When Sacramento County made its decision, Evans said, SSHH recalibrated, determining if the organization could continue just serving other contracts.

“We looked at it and said, ‘No, there isn’t a future. How do we stay open long enough to make sure as many people as possible remain housed, as many people as possible remain employed and as many people as possible get paid back?’” Evans said. “And we somehow did that.”

Still, the process has been anything but smooth. And there was no guarantee that every person SSHH had housed would avoid displacement.

How SSHH Worked and Who it Housed

In June, SSHH listed its assets and creditors in a 148-page bankruptcy filing. Liabilities totaled $2.98 million and assets totaled $1.28 million, including many security deposits SSHH still held for properties it had leased, as the organization typically didn’t own the houses its clients lived in.

The filing also provided addresses for more than 100 of SSHH’s leases, many of these properties concentrated around some of Sacramento’s roughest areas.

Visits last summer to a dozen such addresses in south Sacramento showed that the majority of the houses still had SSHH signage up and people living inside.

“I think there’s been a reduction in the number of people housed,” said Ron Javor, who served on SSHH’s board for more than 20 years before quitting in early 2022, and has since been an unpaid consultant to a subordinate nonprofit, Housing Solutions, Inc. “There’s been some really serious attrition. I heard as many as 20 landlords pulled out of the program, and a number of them had more than one unit.”

Some people who’d had housing through SSHH were moved around as properties went offline. The county engaged in landlord recruitment efforts last year to make up for the ones who’d bailed on SSHH. Sacramento County Board of Supervisors member Patrick Kennedy, who served on SSHH’s board in the mid-2000s, said in June that the county was “working with the landlords who weren't paid for a while to help them become whole, or as whole as we possibly can.”

A former SSHH landlord who spoke in late September said that when they recovered their rental property from the nonprofit, it had been trashed and they were owed months of back rent. This person, who did not want to be identified, said the county has reimbursed them for rent.

Julie Clemens, development manager for SHELTER, Inc. said she’s confident her organization won’t have anyone involuntarily go homeless because of this transition.

At an address that no longer had SSHH signage up last June, two women came to the door and said they’d moved in recently but declined to talk further. Meanwhile, at another south Sacramento house that day, Jennifer Ganz and Todd Bowser, who are each formerly homeless, said they were preparing for everyone in their house to move.

The landlord for the house Ganz and Bowser were living in was among those SSHH acknowledged owing money to in its bankruptcy filing. Last May, the owner sent a 30-day notice to terminate tenancy at the property to Laura Wolff of SSHH and Rolf Davidson, a program manager for Sacramento Steps Forward.

Davidson said in September that Sacramento Steps Forward had gone from housing 204 people when it took over management of permanent supportive housing for SSHH to about 176, but that no one had lost their housing. Some people moved on to different housing and some people had died, with the population served on the older side, Davidson explained.

Sacramento Steps Forward had the same number of total properties at the time for permanent supportive housing, with 50, but experienced other impacts with SSHH’s collapse.

“There were some landlords who chose not to participate going forward,” Davidson said. “There were some changes that had to be made in where people were housed.”

Shutting Down Programs

Change is still afoot at former SSHH leased properties, including permanent supportive housing locations that could face closure in the coming months.

In mid-November, Sacramento Steps Forward contracted with Concord-based SHELTER, Inc. to take over managing permanent supportive housing units that SSHH had managed. These include two units in a south Sacramento triplex that Javor owns. Shrader lives in one of these units.

On Feb. 1, a SHELTER, Inc. representative wrote to Javor that the “program was funded by a (HUD) federal housing grant that was not renewed” and that the master lease for the two apartments would be terminated on April 1.

Julie Clemens, development manager for SHELTER, Inc. told California Local that Sacramento Steps Forward brought her organization in to wind down two programs by June 30. This will necessitate closing approximately 31 housing locations and finding new homes for residents if they can’t make separate arrangements with those property owners.

Clemens said she’s confident that her organization, which operates a shelter for the county in the River District and has relationships with landlords in the region, won’t have anyone involuntarily go homeless because of this transition.

“We’ll provide a place if they’ll accept it,” Clemens said.

Shrader doesn’t want to return to the street. But he’s also uneasy about potentially being moved to a bad environment for his new permanent supportive housing.

“You’re housing people that are sick, you’re housing people with problems, you’re housing people that are broken,” Shrader said.

On a visit to his triplex on Feb. 18, Javor chatted amicably with two men, Oscar Darden and Robert Butler, who’d been moved into the property by Sacramento Steps Forward or SHELTER, Inc. in recent months. Javor acknowledged the tricky logistics in front of them. HUD, he told the men, had given him a lot of money. He wasn’t sure if he could rent privately at a high enough rate to make things work.

Javor said on the trip back to his South Land Park home that he hoped to find a resolution in the next week.

The men appeared to be taking the situation in stride. Darden, 67, who was homeless for approximately 30 years, told California Local that he was “nervous and wondering what’s going to happen next.”

Butler, 65, came to Sacramento Self-Help Housing nearly five years ago after being released from prison. He now works as a truck driver and is house leader for the two permanent supportive housing units at Javor’s triplex facing closure. Butler said he isn’t worried about going homeless.

“I was doing this as a part of my parole plan to kind of give back to the community,” Butler said. “I knew it was going to come to an end sooner or later, so I prepared myself.”

Going Homeless

There was always some risk for people SSHH housed to go homeless, even before the organization began to struggle.

“In any given month of operation, even when Self-Help Housing was operating at full bore, there would be transitional things where a landlord would quit the program or things like that,” Cobb said. “Stuff happens.”

Cobb said a “small number” of people went homeless because of SSHH’s collapse, adding, “I think what happened was when, just before the bankruptcy, Self-Help Housing worked diligently to try to transfer people into other programs.”

Told that numbers he’d provided suggested that as many as 100 people might have gone homeless through SSHH’s collapse, Cobb said it was possible. “I think that probably is a high number, but it could have been as high as that,” he said.

Kennedy was skeptical that the number could be that high. “Typically, if something like that happens, my phone would ring off the hook and it has not,” he said.

County officials worked with Baird and organizations including City Net as SSHH was on its way out. “Our primary concern was to make sure nobody lost their housing,” said Emily Halcon, Sacramento County Department of Homeless Services and Housing Director.

Halcon said that no one who’d had scattered-site housing through SSHH left involuntarily because of the transition. She also acknowledged that some people had moved around because a different SSHH contract expired at the end of 2022, appearing to reference the end of SSHH’s PRTS contract.

Cobb acknowledged even 50-100 people going homeless due to SSHH’s collapse would be significant. “Only compared to how bad it could have been was it good,” Cobb said.

There are signs people might have been falling through the cracks as SSHH collapsed in recent years.

Mark Oden, 64, identified himself as a former truck driver who spent time living along the American River some years ago after being injured on the job. He said he’d like to get back to work and that he’d resisted applying for Social Security retirement benefits.

Oden said he went to live at SSHH housing in 2022 but soon went in and out of the hospital and had surgery in April 2023. As of early October, Oden was at an acute care facility in south Sacramento where, he said, he’d spent several months.

“I feel like I’m stuck here,” Oden said.

All in all, SSHH’s final months of operation were a bleak state of affairs. And it was a far cry from the days the nonprofit helped even tough cases get housing.

Coming next week: How Sacramento Self-Help Housing became a force