Local democracy is a complex, expensive process. We explain.

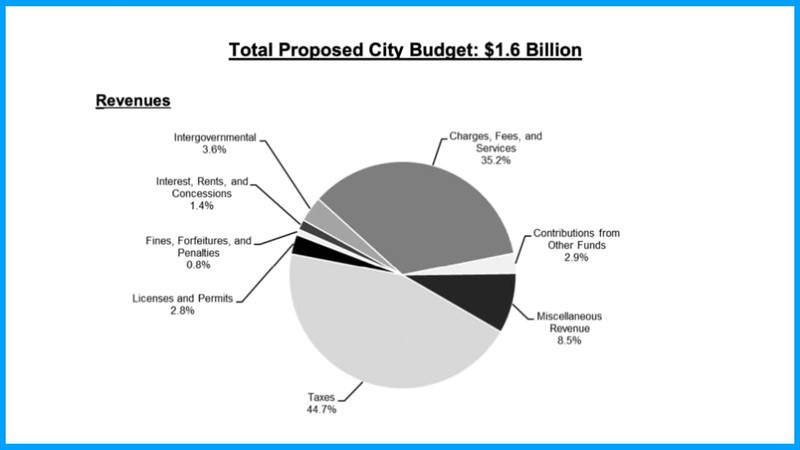

The 2024-2025 City of Sacramento budget is dry reading, but worth it. $1.6 billion worth. Courtesy City of Sacramento.

California municipalities follow a July 1-June 30 fiscal year, and elected representatives and staff spend a lot of time and energy in the annual budgeting process.

Simply put, municipal funds are raised and spent to implement each municipality’s general plan. But crafting annual budgets is anything but simple. The process is made complex due to the variety of revenue sources, duration of funding, constraints on funding use, and the unpredictability of state and federal contributions.

That last issue was especially evident in the 2024-2025 budget cycle when it became apparent that a massive shortfall in the California budget was going to be felt downstream in the municipalities where state grants account for a good chunk of annual revenue.

An Introduction to Municipal Revenues

Again: Local municipal revenues are derived from a number of different sources.

Taxes are classified in two categories—general or special. General taxes, which require voter approval, come without constraints on how the funds are utilized. Special taxes need a two-thirds majority, and come with stipulations on how funds are to be directed.

Municipalities can levy taxes on any property or activity not prohibited by state law, except on items including cigarettes, alcohol, and personal income, which the state taxes.

Taxes contribute an average of 35 percent of municipal revenue, and fall under a few categories:

Fees and Assessments are charges for specific services provided to individuals, such as water, sewer connections, building permits, and recreational classes. These fees must reflect the cost of the service provided. Special benefit assessments fund public improvements benefiting specific property areas, such as upgrades to streets or lighting, and require property-owner approval.

Intergovernmental Sources include funds from state and federal agencies. These monies can be used for general municipal operation and support—things such as local responses to homelessness. The state and federal governments also provide grants to fund specific projects such as wastewater treatment infrastructure.

Other Revenue Sources include such things as rents, franchises, concessions, investment earnings, property sales, debt financing proceeds, and fines.

The Three Funding Categories

Municipal revenues are placed into three classifications: special revenue funds, enterprise funds, and the General Fund.

Special revenue funds are for designated purposes, such as gasoline taxes for road maintenance.

Enterprise funds are self-supporting, based on charges for providing service to users, like drinking water, sewage and refuse collection and disposal..

The General Fund covers revenue not restricted by law to other funds, derived from sales and use taxes, property taxes, and local business taxes.

Constraints and Considerations

To reiterate: Municipal funding exists in a complex web of factors:

Municipalities vs. The State

Local governments have gone straight to voters via the initiative process and successfully added language to the California constitution protecting themselves from actions by the state that threaten their ability to manage municipal budgets. Among them:

Forces Impacting Municipal Revenue Sources

Local budgets can be negatively affected by events outside of the control of a municipality.

As an example, vehicle sales generate significant sales tax revenue, and it was a big deal for the city of Santa Cruz several years ago when the automobile dealerships in town decamped for the neighboring city of Capitola. The same thing happened in the Silicon Valley suburb of Los Gatos when auto dealers moved to San Jose.

Trends which impact the local budgeting process:

How to Get Involved

The spending priorities enumerated in a municipal budget reflect the values of its citizens. As such, you have a right and responsibility to participate in the budget process.

Most municipalities publish current and past budgets on their websites, and many include dashboards and other web-based tools to make it easier for the average citizen to see where funds are coming from and how they are going to be spent.

Many municipalities hold budget meetings and workshops in the spring, with the goal of educating and informing citizens about the budgets taking shape in the current annual cycle.

California Local’s curation of ongoing news and information about local governments make it easy to stay current, and our online government listings make it easy to find local budget information and to reach out to local elected representatives to share your feedback.

How to make use of all this information is up to you.

Learn more

Long form articles which explain how something works, or provide context or background information about a current issue or topic.