The total combined revenues and expenditures of California's 58 counties are astronomical. And getting astronomicaler every year.

The county budget process is complex, involving a lot of moving parts. And holy cow, a lot of money. Santa Clara County Public Domain

California’s 58 counties are established in the constitution as subdivisions of the state, and county governments legally act as agents of the state. As such, counties receive a larger portion of their funding from the state government than do municipalities including towns and cities, with spending constrained by priorities set by the governor and state legislature.

Like municipalities, California counties follow a July 1-June 30 fiscal year, and county supervisors and staff spend a significant amount of time and effort crafting their annual budgets.

But because counties receive a large portion of their revenues from the state, the county budgeting process is intimately entwined with that of the state.

Introduction to the County Budget Process

The California governor is required to present a proposed budget for the upcoming fiscal year by January 10. This gives counties a preliminary view of state policies and priorities and an estimate of state funding available for incorporation into their budgets.

The county budget process thus begins in earnest around the time the proposed state budget is released.

The county administrator begins the budget cycle by weaving together information from the proposed state budget with information from the county board of supervisors to craft instructions for departments including deadlines, spending levels and priorities.

Departments—which often include the county counsel, fire department, department of public works, office of education, department of public health, etc.—usually complete their budget requests by April. The board of supervisors may hold hearings and workshops to gather public input to feed local priorities to the county administrator as they develop the recommended budget for the coming fiscal year.

In May or June, the board of supervisors make the recommended budget available for public review and schedule a public hearing.

By May 14th, the governor releases the May Revision to the state budget. Any changes from the state preliminary budget need to be incorporated by the county administrator into the recommended county budget.

In June, the board of supervisors convene a public budget hearing, and may make revisions to the recommended budget.

The board of supervisors is required to adopt a final budget by June 30.

(Another iteration of budget revisions and adoption may occur after June 30, depending on whether the county uses a one-step or two-step budget process.)

Sources and Organization of County Revenues

There is much overlap in how municipalities and counties fund their annual budgets: taxes, fees and assessments, intergovernmental sources and a grab bag of miscellaneous other lesser sources such as rents, franchises, concessions, investment earnings, property sales, debt financing proceeds, and fines.

Like municipalities, county budgets are organized into three categories: the special fund, the enterprise fund and the general fund.

As already noted, a major difference between municipal and county budgets is that counties receive a larger portion of their budgets from the state, much of which goes into the special revenue fund because their use is constrained to state priorities.

Those priorities generally fall into two broad categories: public safety and public assistance.

California vs. The Counties

A tension exists between the requirement that counties provide specific services as agents of the state and the representation of local choice in how other services and programs are provided. While county budgets can involve billions or hundreds of millions of dollars, in reality, the amount of discretionary spending available to devote to local priorities can be limited.

A number of state propositions have amended the California constitution to constrain the ability of counties to raise funding such as Proposition 13 (1978), Proposition 62 (1986), Proposition 218 (1996), and Proposition 26 (2010).

The state legislature also redirected local property taxes from counties, municipalities and special districts to cover obligations to fund public education in 1992. Legislation establishing the Educational Revenue Augmentation Fund shifted billions of dollars annually back to the state. What was enacted to cover a state budget deficit in 1992 has been left in place and is cause for continuing friction with counties and municipalities.

Another problem is the issue of unfunded mandates imposed by the state on counties and other local governments. Though the “mandate clause” of the California constitution requires the state to pay for any programs imposed on local governments, adequate funding is not always provided and reimbursement is slow, sometimes requiring litigation and intervention by the courts.

This presents challenges to creating county budgets. The job of the county administrator is clearly not an easy one.

How to Get Involved

Because government budgets take in and distribute funds collected from you, the citizen, it’s in your enlightened self-interest to participate in the budget process.

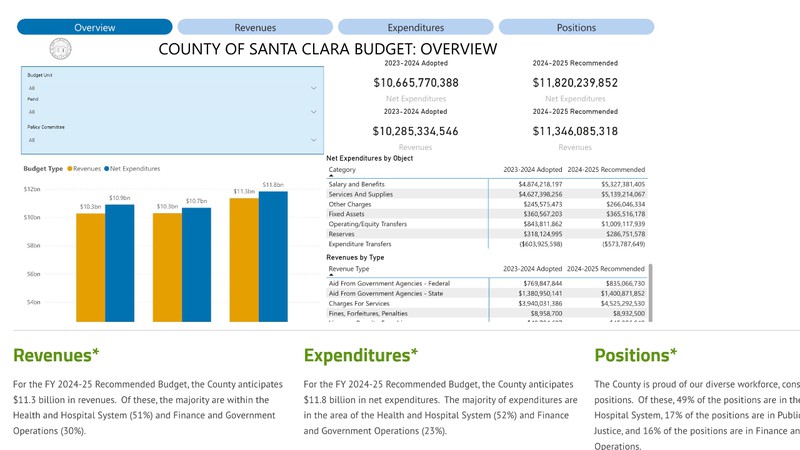

You can start by looking up the current and past budgets for your county on their website. Most counties publish their budgets in easy-to-digest formats on the web, including easy-to-use interactive dashboards and graphs.

All counties are required to hold public hearings to present and discuss annual recommended budgets. Many counties go further by soliciting public input in surveys and in meetings and workshops. These are tremendous opportunities to give feedback and get answers to your questions from your county supervisors and staff.

Write letters to your county supervisors letting them know your input on local priorities.

Because so much of the county budget is derived from state funds and constrained by state legislation and stipulations in the California constitution, your feedback to state legislators and your vote on state propositions have an impact on your local county budget.

In the end, it’s your money, so take an interest and work the system.

Learn More

Long form articles which explain how something works, or provide context or background information about a current issue or topic.