Bank lobbied for lifting regulations that may have prevented its own collapse.

The government has avoided calling its plan to pay off SVB depositors a "bailout." But is it? Cool Caesar / Wikimedia Commons C.C. Share-ALike 4.0 License

On Thursday, March 9, 2023, Silicon Valley Bank CEO Greg Becker already knew that his 40-year-old institution was in trouble. SVB, the bank that provided a financial backbone for California’s technology industry, found itself sitting on about $15 billion in “unrealized” losses in its portfolio of United States Treasury Bonds, against just $16 billion in available capital.

Eight years earlier, Becker had personally asked the United States Congress to loosen the banking regulations imposed after the 2008 financial meltdown, and SVB spent about $500,000 on lobbying to change the law known as Dodd-Frank. Congress passed his hoped-for deregulation in 2018. Then-President Donald Trump signed the changes into law, stating that the regulations were “crushing” smaller banks, and that the rules “just don’t work.”

Five years later, experts say that the rules gutted by the 2018 law would have prevented or at least slowed down the collapse of Silicon Valley Bank. The previous rules would have subjected banks of SVB's size to a series of "stress tests" that would have detected the bank's weaknesses and risk factors, allowing them to be corrected in time to head off calamity.

Becker himself came under scrutiny after the bank folded. According to Securities and Exchange Commission documents, he sold $3.6 million worth of SVB stock on Feb. 27, less than two weeks before SVB shut down. According to media reports, the U.S. Justice Department and the SEC were investigating the collapse, in part to determine whether SVB execs dumped shares when it looked like the bank was going under.

Silicon Valley Relationships: A One-Way Street

At the same time SVB dealt with the squeeze from falling bond prices, tech startups that were the bank’s biggest depositors faced a financial crunch as the industry slowed toward the end of 2022. They needed to burn through cash just to stay afloat, as venture capital funding dried up. So instead of depositing, the startups started withdrawing their money.

Within hours, panicked depositors bankrupted the bank that took big chances on their industry when no other bank would.

That put more pressure on SVB, which announced plans to raise about $2 billion in capital by selling stocks and some of its bonds. The attempt to raise funds, instead of soothing the nerves of its depositors, just freaked them out. So Becker rounded up the bank’s investors for a conference call on March 9, and implored them to keep their money in the troubled bank.

After all, the bank had always been there for the technology industry. According to its website, SVB provided banking services for half of all venture-backed startups not only in Silicon Valley but in the whole United States, as well as 44 percent of all the venture-backed tech and healthcare firms that went public in 2022.

“I would ask everyone to support us just like we supported you,” Becker told the group of leading venture capitalists. But it didn’t work. Becker got a quick, hard lesson in how Silicon Valley relationships work. Within hours, panicked depositors bankrupted the bank that took big chances on their industry when no other bank would, leaving SVB almost a billion dollars in the hole. The next day, the California Department of Financial Protection and Innovation took over the bank and shut it down.

What happened, and what does the largest bank failure in 15 years mean for Silicon Valley?

What Is, or Was, Silicon Valley Bank?

When a bank fails, the biggest fear in the financial sector is “contagion,” that is, the possibility that depositors pulling their funds out of one bank will provoke depositors at other banks to rapidly withdraw their cash as well. Left unchecked, contagion can cause a nationwide, even global financial disaster. That’s exactly what happened in the financial crisis of that began in 2008, when 465 banks went under starting in that year and continuing through 2012. The previous five years had seen only 10 bank closures, with none at all in 2005 and 2006.

Contagion was also the biggest fear when SVB depositors pulled their money. But should it have been? Most banks simply don’t take the risks that SVB took—and that, in fact, were SVB's reason for existing.

The idea for the bank came in 1982 to a pair of Wells Fargo executives, Bill Biggerstaff and Robert Medearis, over a poker game. (Or so the story goes.) Their new bank opened the following year on North First Street in San Jose with the unique business model of providing loans and other financial services to businesses that most banks would dismiss out of hand as dangerous risks—technology start-ups.

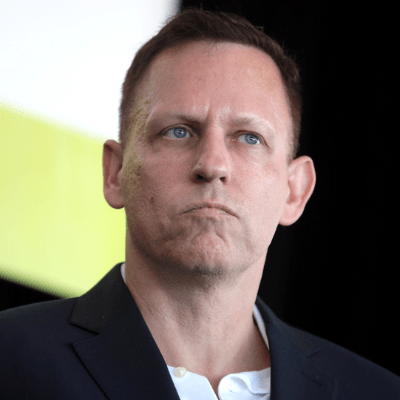

Led by venture capitalist Peter Thiel, depositors withdrew an astonishing $42 billion in just 10 hours.

But the founders and their inaugural CEO Roger Smith were not, as Smith said, “magicians.” They believed they had come up with systems to level out the risks associated with start-up companies, the vast majority of which lose money in their early years if they even survive past that point. The bankers also worked hard and efficiently. By 2014, SVB generated $130,000 in net income per employee, compared to just $30,000 for the much larger Citibank.

Nonetheless, start-up or early stage companies tend to be money losers, meaning that—for a few years—they are more likely to pull money out of the bank to meet payroll and other obligations than to put money in. According to a Reuters report, 39 percent of SVB’s deposits came from early-stage tech and health-technology firms. That meant the bank was always scrambling for liquidity, or as people outside the financial sector call it, cash.

To raise that cash, or “increase liquidity,” the bank relied on selling off pieces of its stock and securities portfolio. When the Fed began jacking up interest rates in March of 2022, ostensibly part of its campaign to curb inflation, the value of SVB’s bond holdings began to head south, culminating a year later in the cash crunch that set off the bank run in March 2023 and brought the bank’s 40-year reign to an unceremonious end.

A Twitter-Fueled Bank Run

The immediate cause of SVB’s sudden failure was a bank run. Led by venture capitalist Peter Thiel—whose Founders Fund pulled millions out of the bank and had nothing left in SVB by late Thursday morning—depositors withdrew an astonishing $42 billion in just 10 hours. By comparison, in the 2008 collapse of Washington Mutual—which remains the largest bank failure in U.S. history—depositors yanked out $16.7 billion over 10 days.

The difference in 2023 was social media, mainly Twitter, as veteran business journalist James Surowiecki wrote in an analysis for The Atlantic.

“Twitter has featured a useful flow of facts and analysis from informed observers and participants on subjects including SVB’s balance sheet, the failures of bank regulation, and the pros and cons of bailing out depositors,” Surowiecki wrote. “But users have also been subjected to a flood of dubious rumors and hysterical predictions of new bank runs.”

A bunch of Twitter users couldn’t goad the federal government into bailing out a bank. Could they?

In 2008, Twitter was a new and unfamiliar platform. A decade-and-a-half later, Twitter was populated by venture capitalists and Silicon Valley entrepreneurs—perhaps most notably Elon Musk, a prolific tweeter who actually bought Twitter itself for $44 billion—who communicated with each other and the public on a near-constant basis.

The online mob drove the speed and suddenness of the run on SVB’s deposits, according to Yale School of Management Professor Andrew Metrick.

“Even back in the ancient days, way before we had any form of modern communication, this stuff tended to be rumors that moved really fast. The reason it would happen is people would walk down the street and observe people standing outside of banks,” Metrick told CNN. “Now we don’t have that, but we have Twitter.”

The Federal Deposit Insurance Commission covers all bank deposits of $250,000 or less, but 90 percent of SVBs depositors had more than that hefty sum in the bank, meaning they wouldn’t get their money back after the bank failure. That didn’t sit well with the tech investors on Twitter, who unleashed an online campaign to force the government into covering all deposits of any size—in effect a federal bailout for the bank’s depositors.

“Their rhetorical strategy of choice was to insist that unless SVB’s depositors were made immediately whole, the entire tech industry and every non-megabank in America would be at risk,” Surowiecki wrote. “Specifically, they said we were facing a ‘Startup Extinction Event’ that would set ‘innovation’ back by 10 years or more. If the Federal Reserve and the FDIC made the wrong decision about SVB’s depositors, that could lead to “a bank run trillions of dollars in size.’”

But a bunch of Twitter users couldn’t goad the federal government into bailing out a bank. Could they?

The Bailout — Or Was It?

Two days after SVB went belly-up, the Biden administration promised that all of the bank’s depositors would be “made whole.” In other words, the federal government would guarantee that everyone with money in the bank would get their money back. All of it. Even account holders with more than the federally insured $250,000 in their accounts would be fully reimbursed.

But was this a bailout? The administration was careful not to invoke that term, which for many Americans conjures images of 2008 when banks deemed “too big to fail” were showered with taxpayer cash to keep them afloat even though the global crisis was caused largely by their own reckless and stupid behavior in chasing after quick and easy profits. In reality, the situation was somewhat more complex, but that’s how the affair persists in public consciousness.

It is true that irresponsible financial practices by some of the country’s largest banks, made permissible by sweeping federal deregulation, was behind the meltdown and subsequent federal bailout in 2008. Was history repeating itself with SVB in 2023?

There are some key differences. Unlike in 2008 when the bailout cash served to keep banks in business, SVB remains defunct. And investors in the bank, according to Pres. Joe Biden, will suffer a wipeout.

“Investors in the banks will not be protected,” Biden said on March 13, in a speech announcing the SVB plan. “They knowingly took a risk and when the risk didn’t pay off, the investors lose their money. That’s how capitalism works.”

'The tech sector is famously full of libertarians who like to denounce big government right up to the minute they themselves needed government aid.'

Paul Krugman, New York Times

Only depositors, who presumably were innocent victims of SVB’s mismanagement, would receive their money back. Unlike in 2008, Biden said, the funds to pay off the depositors would not come from taxpayers but from the FDIC which collects fees from all federally insured banks to cover just such contingencies.

Not all experts were buying it. New York Times columnist Paul Krugman, a Nobel Prize-winning economist, said that no matter what the administration chose to call it, or where the funds were coming from, the SVB plan was indeed a bailout.

“The government came in to rescue depositors who had no legal right to demand such a rescue,” Krugman wrote on March 14. “Furthermore, having to rescue this particular bank and this particular group of depositors is infuriating: Just a few years ago, SVB was one of the midsize banks that lobbied successfully for the removal of regulations that might have prevented this disaster, and the tech sector is famously full of libertarians who like to denounce big government right up to the minute they themselves needed government aid.”

Krugman compared the bailout of SVB not to the 2008 bank bailout, but to the Savings and Loan crisis of the late 1980s, when hundreds of S&L banks—small, local institutions also known as “thrifts” and originally intended to provide affordable loans to homebuyers and small business owners—took on huge financial risks after their activities were deregulated under the Reagan administration. When S&Ls inevitably collapsed countrywide, the government stepped in to make sure depositors retained their money.

The difference, Krugman noted, was that at thrift banks most depositors kept relatively modest sums in their accounts. At SVB, the vast majority of depositors knowingly kept accounts well in excess of the $250,000 federal insurance limit.

How much in excess? Roku, makers of a popular streaming video device of the same name, had $487 million parked at SVB—26 percent of the company’s total cash. Online video game platform Roblox kept deposits of about $150 million. And Circle, a company that handles cryptocurrency payments, said on its Twitter account that $3.3 billion worth of its crypto remained in accounts at SVB.

Those depositors had to be aware that if the bank went under, without a federal bailout they would lose a large portion of their money. But perhaps due to the cozy relationship between SVB and the tech industry, they never considered the possibility that the bank would fail—much less that they, themselves, would trigger the failure by making a run on the bank. On the other hand, as journalist Timothy Noah suggested in an essay for The New Republic, perhaps they were just stupid.

“Or maybe I’m the dumb one to assume that it matters in the slightest how stupid American business is about where it puts its money,” Noah wrote. “In the end it didn’t matter because the idiot depositors got a government bailout.”