Jan Sramek disavows techno-libertarian 'Network State,' explains why master-planned cities are All-American, and talks of his love for walkable communities.

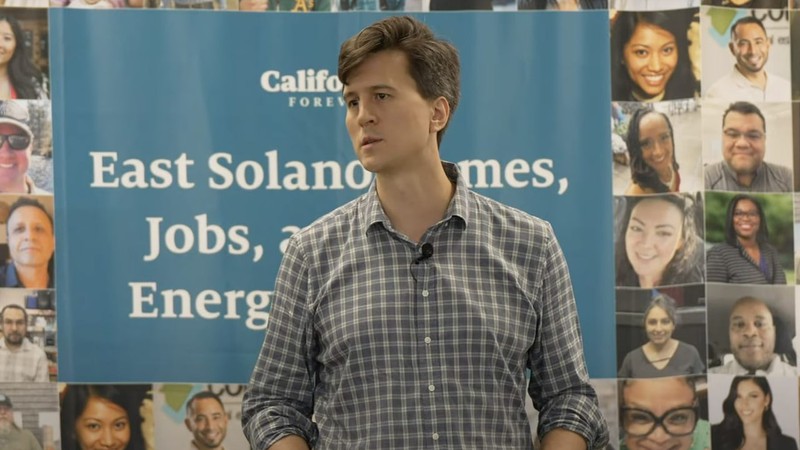

California Forever CEO Jan Sramek announces that he has gathered enough signatures to get his plan on the November ballot in Solano County.

Jan Sramek, who has raised nearly $1 billion toward his dream of building a new city on the California Delta between San Francisco and Sacramento, swears that he believes in democracy.

Sramek did so in response to a grilling by Kara Swisher (“Silicon Valley’s Most Feared and Well-Liked Journalist”) and the business author Scott Galloway on their podcast, Pivot. The interview took place the day after Sramek’s company, California Forever, announced that it had gathered enough signatures to qualify an initiative for the ballot in Solano County—the next step in the company’s plan for a high-tech, green, walkable city of 400,000 on 60,000-acres of what is now marginal ranch land.

Swisher asked Sramek the “democracy” question no less than three times during their 30-minute conversation. She mentioned reports about California Forever‘s connection to “a movement that wants to build a place where a tech elite can live under their own rules.” She noted that Michael Moritz, the VC who is among California Forever’s prominent tech-billionaire investors, had mentioned “innovations in governance” while discussing the project.

And she pointed out that several of California Forever’s investors have been very active in San Francisco politics lately, including the bitterly divisive recall of former district attorney Chesa Boudin.

Galloway told Sramek that “the thing that sent chills down [his] spine” were reports linking California Forever with the techno-libertarian activist Balaji Srinivasan, a former partner at the VC firm Andreessen Horowitz, whose “Network State” movement is decidedly anti-democratic (to put it mildly).

In what amounts to the most significant interview he has done since the New York Times broke the California Forever story last August, Sramek disavowed any connection to Srinavasan and his movement. He admitted that the tech community has created a lot of baggage around the topic of city-building, from Peter Thiel’s vision of floating cities on international waters beyond the reach of any government, to Elon Musk’s proposed outpost on Mars. “We are not trying to do any of that," Sramek said flatly. “I have zero interest in any of it.”

“I think what Mike [Moritz] was referring to in an email … was new kind of governance when it comes to making it easy to build. The thing that we’ve been obsessed with since the beginning is, why does it take two years to get a permit to build a small apartment building in San Francisco?”

(Here Swisher interjected that when she lived in San Francisco, it took forever just to add a door to her home.)

Sramak pointed to the language of the detailed, 88-page ballot measure, the East Solano Homes, Jobs, and Clean Energy Initiative. “The only innovation in governance that’s in it says it should be easy here to build buildings. We are going to do an environmental impact report on the whole community. We’re going to study all of the impacts, and then we’re going to say ‘as long as you’re building something that fits in here, you should be able to get a building permit in 60 days.’ That’s the only governance innovation that we have.”

Swisher: “But the governance is democracy, correct?” Sramek: “Absolutely.”

A Passion for City Planning

The Czeck-born Sramek, who has been pursuing this dream for six years, seems to be driven by two forces. The first is the troubling fact that buying a home has become an unattainable goal for most people in the Bay Area—especially young families.

“We are trying to get California to build again, and solve this problem that we have,” he says. “It’s still the center of innovation. It’s still the economic engine for the whole country. This is the first time in history … where people are moving out of a place like that.”

If we take him at his word, Sramek is also motivated by a love for a well-planned urban environment, in particular walkable cities.

“I really care about the built environment,” he says.“I really think that walkable, dense places are special. I think walkable cities have an amazing impact—the sense of community and creativity and human health. Knowing your neighbors… For me, the primary interest has always been: How do we build more housing so there’s more opportunity? And then: How do we make the place walkable?”

He points to San Francisco neighborhoods like the Marina, Noe Valley, and the mission, as well as places like Georgetown in DC, or the West Village in Manhattan.

“It’s clear that a huge proportion of Americans love these places,” he says, “but they’ve all become oases for the rich—because we stopped building them.”

In response to critics who find it abominable that billionaire investors would build a city with private money, he says, that having studied the topic for years now, he has learned that this has always been the American way. He says Savannah, GA, PhiladelphiaPA and Irvine CA all followed the same playbook he is running.

“We have a lot of really good examples of places that were basically started by a company,” he says.

And as for creating a city by drawing a plan and plopping it in the middle of nowhere, he says that is exactly how the nearby communities of Rio Vista, Benicia, and Vallejo were built.

In reporting the advancement of the initiative, the Valejo Sun pointed out that California Forever still has enormous obstacles to overcome, including the massive traffic pressure he project will add to local highways, potential conflicts with nearby Travis Air Force Base and, of course, where the development is going to get its water.