About 9 percent of all borrowers who were eligible for relief lived in California.

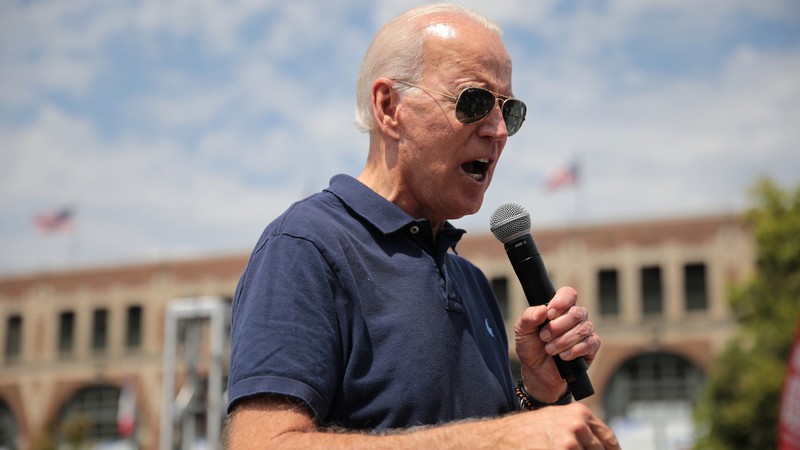

Pres. Joe Biden decried the "hypocrisy" behind the Supreme Court's student loan forgiveness cancellation. Gage Skidmore / Wikimedia Commons C.C. Attribution-Share Alike 2.0 License

As many as 2.3 million Californians were left frustrated and disappointed after the U.S. Supreme Court on June 30 scrapped Pres. Joe Biden’s student debt relief program. That’s the approximate number of borrowers in the state who applied for loan forgiveness under the program, or were deemed automatically eligible, about nine percent of all applicants in the country.

For those California borrowers the $10,000 in debt they could have seen canceled (for those earning below $125,000 per year) was only part of the benefit they would have received. On May 15, Gov. Gavin Newsom signed a bill that would have made that money non-taxable. With more than 3.5 million student debt-holders eligible to apply for forgiveness in California (as opposed to the number who have already applied), that tax plan would have given those Californians an additional $1.3 billion in tax relief, or a tax break as high as $1,860 for some people.

How were Nebraska and the five other states injured by Biden’s plan to relieve some former students of their often crushing debt obligations? The answer is, they weren’t.

The federal government would not tax the forgiven debt, either, but at least seven states were planning to do so, with others yet to revise their tax laws to exempt the sums covered by the Biden program.

About two of every three eligible Californians were Pell Grant recipients, meaning they would be eligible for $20,000 in debt relief under the Biden program.

But all of that disappeared with the 6-3 Supreme Court decision in the case Biden v. Nebraska. Why did the six-justice conservative SCOTUS majority make that decision? And what happens now for student debt payers who suddenly find themselves with $10,000 or $20,000 less money than they thought they had.

Why Did the Supreme Court Even Take This Case?

The first issue the court had to decide was whether to take the case at all. If you want to sue someone, you must have what courts call “standing.” In other words, you need a very specific reason to sue. In an earlier case, the Supreme Court held that to have standing, a plaintiff must pass three tests.

There must be an “injury in fact,” meaning a specific harm, usually financial or physical (or both) and not merely a “generalized grievance” of the kind that affects the public and not specifically the person doing the suing. Next, that injury must be directly caused by some action of the defendant. And finally, the court must be able to somehow help heal, or “redress” the injury.

How were Nebraska and the five other states injured by Biden’s plan to relieve some former students of their often crushing debt obligations?

The answer is, they weren’t—and the Supreme Court readily conceded that they weren’t. Except for one state, Missouri. And even so, Chief Justice John Roberts wrote, it wasn’t exactly the state itself that suffered the injury. It was a rather obscure nonprofit company called the Missouri Higher Education Loan Authority, or MOELA, who supposedly stands to be injured, by allegedly missing out on $44 million in fees.

MOHELA is an entity created by the state government of Missouri, so according to Chief Justice John Roberts, in his majority opinion, “the harm to MOHELA in the performance of its public function is necessarily a direct injury to Missouri itself.”

“The main effect of this doctrine—meant to restore lawmaking authority to Congress—is to hand immense discretionary power to unelected judges.”

JAMELLE BOUIE, NEW YORK TIMES

There’s only one problem. MOHELA doesn’t see it that way. And neither did a federal judge in a lower court. The company has publicly stated that it has no involvement in the lawsuit. In a May 2023 study, the Roosevelt Institute think tank, in collaboration with the Debt Collective—which describes itself as “the nation’s first debtor’s union”—found the claim that MOHELA would lose money to be “fundamentally false.”

To the contrary, the study found, due to fees from picking up loans dropped by other companies, “MOHELA's direct loan revenue will actually be larger than at any prior point in the company's existence, 88 percent higher than the previous year.”

When Biden v. Nebraska first went before a federal judge in 2022, it was thrown out due to lack of standing. Judge Henry E. Autry, who was appointed by Republican Pres. George W. Bush, ruled that MOHELA and the state were financially separate and the state had no obligation to pay the company’s debts.

That means that MOHELA, according to Autrey, is not an “arm of the state,” and “Missouri has not met its burden to show that it can rely on harms allegedly suffered by MOHELA.”

Nonetheless, the case went ahead on appeal until it got to the Supreme Court where Roberts and the five other Republican-appointed justices disagreed.

Major Questions: Why SCOTUS Ended Biden’s Debt Relief Program

With the issue of “standing” out of the way, Roberts went on to rule that Biden’s student debt forgiveness program was unconstitutional due to something called the “major questions doctrine.”

The major questions doctrine states, essentially, that government agencies cannot issue regulations that deal with “major questions” unless Congress has specifically authorized them to do so. The doctrine materialized in a 2000 Supreme Court case, FDA v. Brown & Williamson Tobacco Corp., in which the court ruled that the federal Food and Drug Administration had no authority to regulate tobacco products—not because, as the FDA asserted, nicotine was not a drug, but because “it is extremely unlikely that Congress could have intended to place tobacco within the ambit of the Food and Drug Administration’s regulatory jurisdiction,” the court decided.

Historically, the major questions doctrine has been used mostly by conservative justices to negate regulations on business. “If a majority of the Court deems a regulation to be too significant, it will strike it down unless Congress very explicitly authorized that particular regulation,” explained Vox.com SCOTUS correspondent Ian Millheiser, who also called the doctrine “fake” with “no basis in any law or any provision of the Constitution.”

So did Congress authorize the Department of Education, the agency administering the forgiveness program, to forgive student debt? According to the administration the 2003 HEROES Act, passed in the wake of the 9/11 terrorist attacks, allowed the Education Department to “waive or modify any statutory or regulatory provision applicable to the student financial assistance programs ... as the Secretary deems necessary in connection with a war or other military operation or national emergency.”

The Supreme Court decision “perpetuates a system that prioritizes financial institutions’ interests over the well-being of individuals.”

AFIFA CHAUDRY & DR. BENJAMIN M. DRURY, CHICAGO EDUCATION ADVOCACY COOPERATIVE

Because the COVID-19 pandemic was a national emergency, the Biden administration said it had the power to forgive a certain portion of student loan debt—an option which would seem clear from the “waive or modify” language of the 20-year-old law. But in his majority opinion, Roberts somehow interpreted the language of the HEROES Act to mean that agencies are allowed to make “modest adjustments and additions to existing regulations, not transform them.”

“The main effect of this doctrine—meant to restore lawmaking authority to Congress—is to hand immense discretionary power to unelected judges,” wrote New York Times columnist Jamelle Bouie.

In a dissenting opinion Justice Elena Kagan not only disagreed with Roberts and the conservative majority, she questioned whether their decision was, itself, constitutional.

“Today’s opinion departs from the demands of judicial restraint,” Kagan, appointed by Pres. Barack Obama in 2010, wrote. “At the behest of a party that has suffered no injury, the majority decides a contested public policy issue properly belonging to the politically accountable branches and the people they represent. That is a major problem not just for governance, but for democracy too.

The True Cost of Student Debt

Student loan debt isn’t what it used to be. The average amount owed by borrowers as of 2022 was $37,600, according to the Education Data Initiative (EDI). That’s more than twice as much as 15 years earlier, in 2007, when that debt figure stood at $18,200.

The cost of higher education and, as a result, the skyrocketing debt load has a significant number of borrowers simply underwater. As of 2020, according to EDI data, nine percent of borrowers who attended public colleges and universities were behind on their payments, and seven percent of those who attended private, nonprofit institutions are in the same boat. The borrowers that are worst off are the ones who went to private for-profit schools. A stunning 24 percent were behind on their payments in 2020.

And as of July 2020, 11.2 percent told EDI they had not been able to make a single payment to that point in the year.

Nonetheless, following the Supreme Court decision, borrowers—whose payments had been paused with no additional interest since March of 2020 as a pandemic emergency measure—now must start paying again in October of 2023, with interest starting to accrue in September.

The Consumer Financial Protection Bureau warned in June that 20 percent of borrowers may have difficulty resuming payments once they start up again.

“These Republican officials just couldn’t bear the thought of providing relief for working class, middle class Americans.”

PRES. JOE BIDEN

Another survey, taken in 2022 by the Student Debt Crisis Center (SDCC), found that nearly nine of every 10 borrowers felt that they were not financially secure enough to resume making payments as of February of that year. All of the borrowers in the survey were fully employed, according to SDCC. More than one of four (27 percent) said that at least one-third of their total income would have to go to make their monthly student loan payments.

The toll goes beyond what shows up in the bank balances of many borrowers. A 2017 survey by SoFi Bank found 50 percent of the borrowers surveyed said they experienced depression and 35 percent said they experienced sleep loss from worry over student debt. In fact, 15 percent said that they had talked to a therapist “at least a few times” about their anxiety over their student debt, and another seven percent said they would like to—but they can’t afford a therapist.

“Financial burdens imposed by student loans have long-lasting effects on individuals’ mental health,” wrote Afifa Chaudry and Dr. Benjamin M. Drury of the Chicago Education Advocacy Cooperative. “Borrowers are stalling their careers, holding off on starting a family, struggling to find work, and balancing trying to find a job with part-time work to keep food on their plate.”

The Supreme Court decision “perpetuates a system that prioritizes financial institutions’ interests over the well-being of individuals,” Chaudry and Drury wrote.

What Now For Those Who Owe?

Biden decried the “hypocrisy” of Republicans that he said led to the Supreme Court decision.

“These Republican officials just couldn’t bear the thought of providing relief for working class, middle class Americans,” Biden said shortly after the SCOTUS decision came down, also declaring that “the court misinterpreted the Constitution.”

But the president also announced measures to ease the burden on stressed student loan borrowers.

Biden said that while the pause of more than three years will end, those who have trouble making payments will not face some of the worst consequences due to a one-year “on ramp.” During that year running through the end of September, 2024, loan-holders who miss payments won’t be reported to credit bureaus and their loans will not go into default. There will be no late fees, even though interest will be charged whether payments are made or not.

He also announced a new program that he said he hopes will put the loan forgiveness back in action. This time, Biden said he would rely on the Higher Education Act of 1965. The law authorizes the Education Department to "compromise, waive or release loans."

The administration did not announce any details about how the new debt relief plan would work, and the rulemaking process to iron out those details may take months, Bharat Ramamurti, deputy director of the National Economic Council told ABC News.

The process may even take a full year, experts said, meaning that if it is carried through to completion, the new debt relief plan would be finalized just weeks before the 2024 presidential election.

Long form articles which explain how something works, or provide context or background information about a current issue or topic.